Gallup on Social Media: Just One, Tiny, Irrelevant Data Point Missing

October 23, 2023

![Vea4_thumb_thumb_thumb_thumb_thumb_t[2] Vea4_thumb_thumb_thumb_thumb_thumb_t[2]](https://arnoldit.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Vea4_thumb_thumb_thumb_thumb_thumb_t2_thumb-25.gif) Note: This essay is the work of a real and still-alive dinobaby. No smart software involved, just a dumb humanoid.

Note: This essay is the work of a real and still-alive dinobaby. No smart software involved, just a dumb humanoid.

I read “Teens Spend Average of 4.8 Hours on Social Media Per Day.” I like these insights into how intelligence is being whittled away.

Me? A dumb bunny. Thanks, MidJourney. What dumb bunny inspired you?

Three findings caught may attention and one, tiny, irrelevant data point I noticed was missing. Let’s look at three of the hooks snagging me.

First, the write up reveals:

Across age groups, the average time spent on social media ranges from as low as 4.1 hours per day for 13-year-olds to as high as 5.8 hours per day for 17-year-olds.

Doesn’t that seem like a large chunk of one’s day?

Second, I learned that the research unearthed this insight:

Teens report spending an average of 1.9 hours per day on YouTube and 1.5 hours per day on TikTok

I assume the bright spot is that only two plus hours are invested in reading X.com, Instagram, and encrypted messages.

Third, I learned:

The least conscientious adolescents — those scoring in the bottom quartile on the four items in the survey — spend an average of 1.2 hours more on social media per day than those who are highly conscientious (in the top quartile of the scale). Of the remaining Big 5 personality traits, emotional stability, openness to experience, agreeableness and extroversion are all negatively correlated with social media use, but the associations are weaker compared with conscientiousness.

Does this mean that social media is particularly effective on the most vulnerable youth?

Now let me point out the one item of data I noted was missing:

How much time does this sample spend reading?

I think I know the answer.

Stephen E Arnold, October 23, 2023

Recent Facebook Experiments Rely on Proprietary Meta Data

September 25, 2023

When one has proprietary data, researchers who want to study that data must work with you. That gives Meta the home court advantage in a series of recent studies, we learn from the Science‘s article, “Does Social Media Polarize Voters? Unprecedented Experiments on Facebook Users Reveal Surprises.” The 2020 Facebook and Instagram Election Study has produced four papers so far with 12 more on the way. The large-scale experiments confirm Facebook’s algorithm pushes misinformation and reinforces filter bubbles, especially on the right. However, they seem to indicate less influence on users’ views and behavior than many expected. Hmm, why might that be? Writer Kai Kupferschmidt states:

“But the way the research was done, in partnership with Meta, is getting as much scrutiny as the results themselves. Meta collaborated with 17 outside scientists who were not paid by the company, were free to decide what analyses to run, and were given final say over the content of the research papers. But to protect the privacy of Facebook and Instagram users, the outside researchers were not allowed to handle the raw data. This is not how research on the potential dangers of social media should be conducted, says Joe Bak-Coleman, a social scientist at the Columbia School of Journalism.”

We agree, but when companies maintain a stranglehold on data researchers’ hands are tied. Is it any wonder big tech balks at calls for transparency? The article also notes:

“Scientists studying social media may have to rely more on collaborations with companies like Meta in the future, says [participating researcher Deen] Freelon. Both Twitter and Reddit recently restricted researchers’ access to their application programming interfaces or APIs, he notes, which researchers could previously use to gather data. Similar collaborations have become more common in economics, political science, and other fields, says [participating researcher Brendan] Nyhan. ‘One of the most important frontiers of social science research is access to proprietary data of various sorts, which requires negotiating these one-off collaboration agreements,’ he says. That means dependence on someone to provide access and engage in good faith, and raises concerns about companies’ motivations, he acknowledges.”

See the article for more details on the experiments, their results so far, and their limitations. Social scientist Michael Wagner, who observed the study and wrote a commentary to accompany their publication, sees the project as a net good. However, he acknowledges, future research should not be based on this model where the company being studied holds all the data cards. But what is the alternative?

Cynthia Murrell, September 25, 2023

Useful Probability Wording from the UK Ministry of Defence

August 8, 2023

Note: This essay is the work of a real and still-alive dinobaby. No smart software involved, just a dumb humanoid.

Note: This essay is the work of a real and still-alive dinobaby. No smart software involved, just a dumb humanoid.

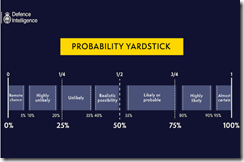

“Have You Ever Wondered Why Defence Intelligence Uses Terms Like “Unlikely” or “Realistic Possibility” When We Assess Russia’s War in Ukraine?” provides two useful items of information. Many people will be familiar with the idea of a “probability yardstick.” Others — like some podcast pundits and YouTube yodas — may not have a firm grasp on the words and their meaning.

I have reproduced the Ministry of Defence’s Probability Yardstick, which appeared in February 2023 in the unclassified posting:

Some investment analysts and business consultants have adopted this or a similar “yardstick.” Many organizations have this type of visual representation of event likelihoods.

The article does not provide real-life examples of the use of the yardstick. That’s is a good decision. For those engaged in analysis and data crunching, the idea of converting “numbers” into a point on a yardstick facilitates the communication of risk.

Here’s one recent example. A question like the impact of streaming on US cable companies is presented in the article “As Cable TV is Losing Millions of Subscribers, YouTube TV Is Now The 5th Largest TV Provider & Could Soon Be The 4th Largest” does not communicate the type of information a senior executive wants; that is, how likely is it the trend will continue. Pegging the loss of subscribers on the yardstick in either the “likely or probable” or “highly likely” communicates quickly and without word salad. The “explanation” can, of course, be provided.

In fast-moving situations, the terminology of the probability yardstick and its presentation of what is a type of confidence score is often useful. By the way, in the cited Cable TV article, the future is sunny for Google and TikTok, but not so good for the traditional companies.

Stephen E Arnold, August 8, 2023

Research 2023: Is There a Methodology of Control via Mendacious Analysis

August 8, 2023

Note: This essay is the work of a real and still-alive dinobaby. No smart software involved, just a dumb humanoid.

Note: This essay is the work of a real and still-alive dinobaby. No smart software involved, just a dumb humanoid.

I read “How Facebook Does (and Doesn’t) Shape Our Political Views.” I am not sure what to conclude from the analysis of four studies about Facebook (is it Zuckbook?) presumably completed with some cooperation from the social media giant itself. The message I carried away from the write up is that tainted research may be the principal result of these supervised studies.

The up and coming leader says to a research assistant, “I am telling you. Manipulate or make up the data. I want the results I wrote about supported by your analysis. If you don’t do what I say, there will be consequences.” MidJourney does know how to make a totally fake leader appear intense.

Consider the state of research in 2023. I have mentioned the problem with Stanford University’s president and his making up data. I want to link the Stanford president’s approach to research with Facebook (Meta). The university has had some effect on companies in the Silicon Valley region. And Facebook (Meta) employs a number of Stanford graduates. For me, then, it is logical to consider the approach of the university to objective research and the behavior of a company with some Stanford DNA to share certain characteristics.

“How Facebook Does (and Doesn’t) Shape Our Political Views” offers this observation based on “research”:

“… the findings are consistent with the idea that Facebook represents only one facet of the broader media ecosystem…”

The summary of the Facebook-chaperoned research cites an expert who correctly in my my identifies two challenges presented by the “research”:

- Researchers don’t know what questions to ask. I think this is part of the “don’t know what they don’t know.” I accept this idea because I have witnessed it. (Example: A reporter asking me about sources of third party data used to spy on Americans. I ignored the request for information and disconnected from the reporter’s call.)

- The research was done on Facebook’s “terms”. Yes, powerful people need control; otherwise, the risk of losing power is created. In this case, Facebook (Meta) wants to deflect criticism and try to make clear that the company’s hand was not on the control panel.

Are there parallels between what the fabricating president of Stanford did with data and what Facebook (Meta) has done with its research initiative? Shaping the truth is common to both examples.

In Stanford’s Ideal Destiny, William James said this about about Stanford:

It is the quality of its men that makes the quality of a university.

What links the actions of Stanford’s soon-to-be-former president and Facebook (Meta)? My answer would be, “Creating a false version of objective data is the name of the game.” Professor James, I surmise, would not be impressed.

Stephen E Arnold, August 8, 2023

Research: A Suspicious Activity and Deserving of a Big Blinking X?

August 2, 2023

Note: This essay is the work of a real and still-alive dinobaby. No smart software involved, just a dumb humanoid.

Note: This essay is the work of a real and still-alive dinobaby. No smart software involved, just a dumb humanoid.

The Stanford president does it. The Harvard ethics professor does it. Many journal paper authors do it. Why can’t those probing the innards of the company formerly known as Twatter do it?

I suppose those researchers can. The response to research one doesn’t accept can be a simple, “The data processes require review.” But no, no, no. The response elicited from the Twatter is presented in “X Sues Hate Speech Researchers Whose Scare Campaign Spooked Twitter Advertisers.” The headline is loaded with delicious weaponized words in my opinion; for instance, the ever popular “hate speech”, the phrase “scare campaign,” and “spooked.”

MidJourney, after some coaxing, spit out a frightened audience of past, present, and potential Twatter advertisers. I am not sure the smart software captured the reality of an advertiser faced with some brand-injuring information.

Wording aside, the totally objective real news write up reports:

X Corp sued a nonprofit, the Center for Countering Digital Hate (CCDH), for allegedly “actively working to assert false and misleading claims” regarding spiking levels of hate speech on X and successfully “encouraging advertisers to pause investment on the platform,” Twitter’s blog said.

I found this statement interesting:

X is alleging that CCDH is being secretly funded by foreign governments and X competitors to lob this attack on the platform, as well as claiming that CCDH is actively working to censor opposing viewpoints on the platform. Here, X is echoing statements of US Senator Josh Hawley (R-Mo.), who accused the CCDH of being a “foreign dark money group” in 2021—following a CCDH report on 12 social media accounts responsible for 65 percent of COVID-19 vaccine misinformation, Fox Business reported.

Imagine. The Musker questioning research.

Exactly what is “accurate” today? One could query the Stanford president, the Harvard ethicist, Mr. Musk, or the executives of the Center for Countering Digital Hate. Wow. That sounds like work, probably as daunting as reviewing the methodology used for the report.

My moral and ethical compass is squarely tracking lunch today. No attorneys invited. No litigation necessary if my soup is cold. I will be dining in a location far from the spot once dominated by a quite beefy, blinking letter signifying Twatter. You know. I think I misspelled “tweeter.” I will fix it soon. Sorry.

Stephen E Arnold, August 2, 2023

Whom Does One Trust? Surprise!

July 7, 2023

![Vea4_thumb_thumb_thumb_thumb_thumb_t[1] Vea4_thumb_thumb_thumb_thumb_thumb_t[1]](http://arnoldit.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/Vea4_thumb_thumb_thumb_thumb_thumb_t1_thumb-13.gif) Note: This essay is the work of a real and still-alive dinobaby. No smart software involved, just a dumb humanoid.

Note: This essay is the work of a real and still-alive dinobaby. No smart software involved, just a dumb humanoid.

Whom does one trust? The answer — according to the estimable New York Post — is young people. Believe it or not. Just be sure to exclude dinobabies and millennials, of course.

“Millennials Are the Biggest Liars of All Generations, Survey Reveals”:

A new survey found that of all generations, those born between 1981 and 1996 are the biggest culprits of lying in the workplace and on social media.

Am I convinced that the survey is spot on? Nah. Am I confident that millennials are the biggest liars when the cohort is considered? Nah.

MidJourney generated this illustration of an angry sales manager confronting a worker. The employee reported sales as closed when they were pending. Who would do this? A dinobaby, a millennial, or a regular sales professional?

Am I entertained by the idea that dinobabies are not the most prone to prevarication and mendacity? Yes.

Consider this statement:

The findings showed that millennials were the worst offenders, with 13% copping to being dishonest at least once a day.

How many times do dinobabies eject a falsehood?

By contrast, only 2% of baby boomers, those born between 1946 and 1964, fibbed once per day.

One must be aware that GenXers just five percent engage in “daily deception.”

Where do people take liberties with the truth? Résumés (hello, LinkedIn) and social media. Imagine that! Money and companionship.

Who lies the most? Yep, 26 percent of males lie once a day. Twenty-three percent of females emit deceptive statements once a day. No other genders were considered in the write up, which is an important oversight in my opinion.

And who ran the survey? An outfit named PlayStar. Yes! I wonder if the survey tool was a Survey Monkey-like system.

Stephen E Arnold, July 7, 2023

Moral Decline? Nah, Just Your Perception at Work

June 12, 2023

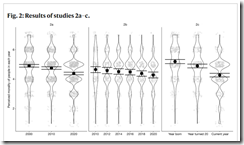

Here’s a graph from the academic paper “The Illusion of Moral Decline.”

Is it even necessary to read the complete paper after studying the illustration? Of course not. Nevertheless, let’s look at a couple of statements in the write up to get ready for that in-class, blank bluebook semester examination, shall we?

Statement 1 from the write up:

… objective indicators of immorality have decreased significantly over the last few centuries.

Well, there you go. That’s clear. Imagine what life was like before modern day morality kicked in.

Statement 2 from the write up:

… we suggest that one of them has to do with the fact that when two well-established psychological phenomena work in tandem, they can produce an illusion of moral decline.

Okay. Illusion. This morning I drove past people sleeping under an overpass. A police vehicle with lights and siren blaring raced past me as I drove to the gym (a gym which is no longer open 24×7 due to safety concerns). I listened to a report about people struggling amidst the flood water in Ukraine. In short, a typical morning in rural Kentucky. Oh, I forgot to mention the gunfire, I could hear as I walked my dog at a local park. I hope it was squirrel hunters but in this area who knows?

MidJourney created this illustration of the paper’s authors celebrating the publication of their study about the illusion of immorality. The behavior is a manifestation of morality itself, and it is a testament to the importance of crystal clear graphs.

Statement 3 from the write up:

Participants in the foregoing studies believed that morality has declined, and they believed this in every decade and in every nation we studied….About all these things, they were almost certainly mistaken.

My take on the study includes these perceptions (yours hopefully will be more informed than mine):

- The influence of social media gets slight attention

- Large-scale immoral actions get little attention. I am tempted to list examples, but I am afraid of legal eagles and aggrieved academics with time on their hands.

- The impact of intentionally weaponized information on behavior in the US and other nation states which provide an infrastructure suitable to permit wide use of digitally-enabled content.

In order to avoid problems, I will list some common and proper nouns or phrases and invite you think about these in terms of the glory word “morality”. Have fun with your mental gymnastics:

- Catholic priests and children

- Covid information and pharmaceutical companies

- Epstein, Andrew, and MIT

- Special operation and elementary school children

- Sudan and minerals

- US politicians’ campaign promises.

Wasn’t that fun? I did not have to mention social media, self harm, people between the ages of 10 and 16, and statements like “Senator, thank you for that question…”

I would not do well with a written test watched by attentive journal authors. By the way, isn’t perception reality?

Stephen E Arnold, June 12, 2023

Probability: Who Wants to Dig into What Is Cooking Beneath the Outputs of Smart Software?

May 30, 2023

Note: This essay is the work of a real and still-alive dinobaby. No smart software involved, just a dumb humanoid.

Note: This essay is the work of a real and still-alive dinobaby. No smart software involved, just a dumb humanoid.

The ChatGPT and smart software “revolution” depends on math only a few live and breathe. One drawer in the pigeon hole desk of mathematics is probability. You know the coin flip example. Most computer science types avoid advanced statistics. I know because my great uncle Vladimir Arnold (yeah, the guy who worked with a so so mathy type named Andrey Kolmogorov, who was pretty good at mathy stuff and liked hiking in the winter in what my great uncle described as “minimal clothing.”)

When it comes to using smart software, the plumbing is kept under the basement floor. What people see are interfaces and application programming interfaces. Watching how the sausage is produced is not what the smart software outfits do. What makes the math interesting is that the system and methods are not really new. What’s new is that memory, processing power, and content are available.

If one pries up a tile on the basement floor, the plumbing is complicated. Within each pipe or workflow process are the mathematics that bedevil many college students: Inferential statistics. Those who dabble in the Fancy Math of smart software are familiar with Markov chains and Martingales. There are garden variety maths as well; for example, the calculations beloved of stochastic parrots.

MidJourney’s idea of complex plumbing. Smart software’s guts are more intricate with many knobs for acolytes to turn and many levers to pull for “users.”

The little secret among the mathy folks who whack together smart software is that humanoids set thresholds, establish boundaries on certain operations, exercise controls like those on an old-fashioned steam engine, and find inspiration with a line of code or a process tweak that arrived in the morning gym routine.

In short, the outputs from the snazzy interface make it almost impossible to understand why certain responses cannot be explained. Who knows how the individual humanoid tweaks interact as values (probabilities, for instance) interact with other mathy stuff. Why explain this? Few understand.

To get a sense of how contentious certain statistical methods are, I suggest you take a look at “Statistical Modeling, Causal Inference, and Social Science.” I thought the paper should have been called, “Why No One at Facebook, Google, OpenAI, and other smart software outfits can explain why some output showed up and some did not, why one response looks reasonable and another one seems like a line ripped from Fantasy Magazine.

In a nutshell, the cited paper makes one point: Those teaching advanced classes in which probability and related operations are taught do not agree on what tools to use, how to apply the procedures, and what impact certain interactions produce.

Net net: Glib explanations are baloney. This mathy stuff is a serious problem, particularly when a major player like Google seeks to control training sets, off-the-shelf models, framing problems, and integrating the firm’s mental orientation to what’s okay and what’s not okay. Are you okay with that? I am too old to worry, but you, gentle reader, may have decades to understand what my great uncle and his sporty pal were doing. What Google type outfits are doing is less easily looked up, documented, and analyzed.

Stephen E Arnold, May 30, 2023

Kiddie Research: Some Guidelines

May 17, 2023

Note: This essay is the work of a real and still-alive dinobaby. No smart software involved, just a dumb humanoid.

Note: This essay is the work of a real and still-alive dinobaby. No smart software involved, just a dumb humanoid.

The practice of performing market research on children will not go away any time soon. It is absolutely vital, after all, that companies be able to target our youth with pinpoint accuracy. In the article “A Guide on Conducting Better Market and User Research with Kids,” Meghan Skapyak of the UX Collective shares some best practices. Apparently these tips can help companies enthrall the most young people while protecting individual study participants. An interesting dichotomy. She writes:

“Kids are a really interesting source of knowledge and insight in the creation of new technology and digital experiences. They’re highly expressive, brutally honest, and have seamlessly integrated technology into their lives while still not fully understanding how it works. They pay close attention to the visual appeal and entertainment-value of an experience, and will very quickly lose interest if a website or app is ‘boring’ or doesn’t look quite right. They’re more prone to error when interacting with a digital experience and way more likely to experiment and play around with elements that aren’t essential to the task at hand. These aspects of children’s interactions with technology make them awesome research participants and testers when researchers structure their sessions correctly. This is no easy task however, as there are lots of methodological, behavioral, structural, and ethical considerations to take in mind while planning out how your team will conduct research with kids in order to achieve the best possible results.”

Skapyak goes on to blend and summarize decades of research on ethical guidelines, structural considerations, and methodological experiments in this field. To her credit, she starts with the command to “keep it ethical” and supplies links to the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child and UNICEF’s Ethical Research Involving Children. Only then does she launch into techniques for wringing the most shrewd insights from youngsters. Examples include turning it into a game, giving kids enough time to get comfortable, and treating them as the experts. See the article for more details on how to better sell stuff to kids and plant ideas in their heads while not violating the rights of test subjects.

Cynthia Murrell, May 17, 2023

Reproducibility: Academics and Smart Software Share a Quirk

January 15, 2023

I can understand why a human fakes data in a journal article or a grant document. Tenure and government money perhaps. I think I understand why smart software exhibits this same flaw. Humans put their thumbs (intentionally or inadvertently) put their thumbs on the button setting thresholds and computational sequences.

The key point is, “Which flaw producer is cheaper and faster: Human or code?” My hunch is that smart software wins because in the long run it cannot sue for discrimination, take vacations, and play table tennis at work. The downstream consequence may be that some humans get sicker or die. Let’s ask a hypothetical smart software engineer this question, “Do you care if your model and system causes harm?” I theorize that at least one of the software engineer wizards I know would say, “Not my problem.” The other would say, “Call 1-8-0-0-Y-O-U-W-I-S-H and file a complaint.”

Wowza.

“The Reproducibility Issues That Haunt Health-Care AI” states:

a data scientist at Harvard Medical School in Boston, Massachusetts, acquired the ten best-performing algorithms and challenged them on a subset of the data used in the original competition. On these data, the algorithms topped out at 60–70% accuracy, Yu says. In some cases, they were effectively coin tosses1. “Almost all of these award-winning models failed miserably,” he [Kun-Hsing Yu, Harvard] says. “That was kind of surprising to us.”

Wowza wowza.

Will smart software get better? Sure. More data. More better. Think of the start ups. Think of the upsides. Think positively.

I want to point out that smart software may raise an interesting issue: Are flaws inherent because of the humans who created the models and selected the data? Or, are the flaws inherent in the algorithmic procedures buried deep in the smart software?

A palpable desire exists and hopes to find and implement a technology that creates jobs, rejuices some venture activities, and allows the questionable idea that technology to solve problems and does not create new ones.

What’s the quirk humans and smart software share? Being wrong.

Stephen E Arnold, January 15, 2023