Alphabet Google Justifies Its R&D Science Club Methods

January 23, 2016

In the midst of the snowmageddon craziness in rural Kentucky, I noted a couple of Alphabet Google write ups. Unlike the sale of shares, the article tackle the conceptual value of the Alphabet Google’s approach to research and development. I view most of Google’s post 2006 research as an advanced version of my high school science club projects.

Our tasks in 1960 included doing a moon measurement from central Illinois. Don’t laugh, Don and Bernard Jackson published their follow on to the science club musing in 1962. In Don’s first University of Illinois astronomy class, the paper was mentioned by the professor. The prof raised a question about the method. Don raised his hand and explained how the data were gathered. The prof was not impressed. Like many mavens, the notion that a college freshman and his brother wrote a paper, got it published, and then explained the method in front of a class of indifferent freshman was too much for the expert. I think the prof shifted to social science or economics, both less rigorous disciplines in my view.

Google’s research interests.

The point is that youth can get some things right. As folks age, the view of what’s right and what’s a little off the beam differ.

Let’s look at the first write up called “How Larry Page’s Obsessions Became Google’s Business.” Note that if the link is dead, you may have to subscribe to the newspaper or hit the library in search of a dead tree copy. The New York Times have an on again and off again approach to the Google. It’s not that the reporters don’t ask the right questions. I think that the “real” journalists get distracted with the free mouse pads and folks like Tony Bennett crooning in the cafeteria to think about what the Google was, is, and has become.

The article points out:

Mr. Page is hardly the first Silicon Valley chief with a case of intellectual wanderlust, but unlike most of his peers, he has invested far beyond his company’s core business and in many ways has made it a reflection of his personal fascinations.

I then learned:

Another question he likes to ask: “Why can’t this be bigger?”

The suggestion that bigger is better is interesting. Stakeholders assume the “bigger” means more revenue and profit. Let’s hope.

Then this insight:

When Mr. Page does talk in public, he tends to focus on optimistic pronouncements about the future and Google’s desire to help humanity.

Optimism is good.

I then worked through “Google Alphabet and Four times the Research Budget of Darpa and Larger Moonshot Ambitions than Darpa.”

The bigger, I thought, may not be revenue. The bigger may be the budget of the science club. If Don and Bernie Jackson could build on the moon data, Google can too. Right?

Proprietary Enterprise Search: False Hopes and Brutal Costs

December 21, 2015

At lunch the other day, the goslings and I engaged in what I thought was a routine discussion: The sad state of the enterprise search market.

I pointed out that the “Enterprise Search Daily” set up by Edwin Stauthamer was almost exclusively a compilation of Big Data articles. Enterprise search, although the title of the daily, was not the focal point of the content.

Enterprise search is a cost black hole. R&D, support, customization, and bug fixes gorge on money and engineers. Instead of adding value to an enterprise system, search becomes the reason the CFO has a migraine and why sales professionals struggle to close deals.

I said, “Enterprise search has disappeared.”

One of the goslings asked, “What’s happened to the proprietary search systems acquired by some big companies?”

We were off an running.

The goslings mentioned that Dassault Systèmes bought Exalead and the brand has disappeared from the US market. IBM bought Vivisimo, and the purchase was explained as a Big Data buy, but the company and its technology have disappeared into the Great Blue Hole, which is today’s IBM. Hummingbird bought Fulcrum, and then OpenText bought Hummingbird. Open Text owns Information Dimension’s BASIS, BRS Search, and its own home brew search system. Oracle snapped up Endeca, InQuira, and RightNow in a barrage of search binge shopping. Lexmark—formerly a unit of Big Blue—bought ISYS Search Software and Brainware. Then there was the famous purchase of Fast Search & Transfer by Microsoft and the subsequent police investigation and the charges filed against a former executive for fancy dancing with the revenue numbers. And who can forget the $11 billion purchase of Autonomy by IBM. There have been other deals, and the goslings enjoyed commenting on this.

I called a halt to the lunch time stand up comedy routine. The executives of these companies were trying to do what they thought was best for their [a] financial future and [b] for their stakeholders. Some of these stakeholders had suffered through revenue droughts and were looking for a way out of the sea of red ink enterprise search vendors generate with aplomb.

The point I raised was, “Does the purchase of a proprietary enterprise search system?” make a substantive contribution to the financial health of the purchasing company.

Reed Elsevier Lexis Nexis Embraces Legal Analytics: No, Not an Oxymoron

November 27, 2015

Lawyers and legal search and content processing systems do words. The analytics part of life, based on my limited experience of watching attorneys do mathy stuff, is not these folks’ core competency. Words. Oh, and billing. I can’t overlook billing.

I read “Now It’s Official: Lexis Nexis Acquires Lex Machina.” This is good news for the stakeholders of Lex Machina. Reed Elsevier certainly expects Lex Machina’s business processes to deliver an avalanche of high margin revenue. One can only raise prices so far before the old chestnut from Economics 101 kicks in: Price elasticity. Once something is too expensive, the customers kick the habit, find an alternative, or innovate in remarkable ways.

According to the write up:

LexisNexis today announced the acquisition of Silicon Valley-based Lex Machina, creators of the award-winning Legal Analytics platform that helps law firms and companies excel in the business and practice of law.

So what does legal analytics do? Here’s the official explanation, which is in, gentle reader, words:

- A look into the near future. The integration of Lex Machina Legal Analytics with the deep collection of LexisNexis content and technology will unleash the creation of new, innovative solutions to help predict the results of legal strategies for all areas of the law.

- Industry narrative. The acquisition is a prominent and fresh example of how a major player in legal technology and publishing is investing in analytics capabilities.

I don’t exactly know what Lex Machina delivers. The company’s Web page states:

We mine litigation data, revealing insights never before available about judges, lawyers, parties, and patents, culled from millions of pages of IP litigation information. We call these insights Legal Analytics, because analytics involves the discovery and communication of meaningful patterns in data. Our customers use to win in the highly competitive business and practice of law. Corporate counsel use Lex Machina to select and manage outside counsel, increase IP value and income, protect company assets, and compare performance with competitors. Law firm attorneys and their staff use Lex Machina to pitch and land new clients, win IP lawsuits, close transactions, and prosecute new patents.

I think I understand. Lex Machina applies the systems and methods used for decades by companies like BAE Systems (Detica/ NetReveal) and similar firms to provide tools which identify important items. (BAE was one of Autonomy’s early customers back in the late 1990s.) Algorithms, not humans reading documents in banker boxes, find the good stuff. Costs go down because software is less expensive than real legal eagles. Partners can review outputs and even visualizations. Revolutionary.

Big Data: Systems of Insight

October 6, 2015

I read “All Your Big Data Will Mean Nothing without Systems of Insight.” The title reminded me of the verbiage generated by mid tier consulting firms and adjuncts teaching MBA courses at some institutions of higher learning. Malarkey, parental advice, and Big Data—a Paula Dean-type recipe for low-calorie intellectual fare.

Can one live on the outputs of mid tier consulting firm lingo prepared to be fudgier?

The notion of a system of insight is not particularly interesting. The rhetorical trip of moving from a particular to a more general concept fools some beginning debaters. For a more experienced debater, the key is to keep the eye on the ball, which, in this case, is the tenuous connection between Big Data and strategic management methods. (I am not sure these exist even after reading every one of Peter Drucker’s books.)

But I like to deal with particulars.

Computerworld is a sister or first cousin unit of the IDC outfit which sold my research on Amazon without asking my permission. My valiant legal eagle was able to disappear the report. I was concerned with the connection of my name and the names of two of my researchers with the IDC outfit. I have presented some of the back story in previous blog posts. I included screenshots along with the details of not issuing a contract, using content in ways to which I would never agree, and engaging in letters with my attorney offering inducements to drop the matter. Wow. A big company is unable to get organized and then pays its law firm to find a solution to the self created problem.

The report in question was a limp wristed, eight pages in length and available to Amazon’s eager readers of romance novels for a mere $3,500. Hey, the good stuff in our research was chopped out, leaving a GrapeNut flakes experience for those able to read the document. I am a lousy writer, but I try to get my points across in a colorful way. Cereal bowl writing is not for me.

What does this have to do with Big Data and a system of insights?

Aren’t Amazon’s sales data big? Isn’t it possible to look at what sells on Amazon by scanning the company’s public information about books? Won’t a casual Google search reveal information about Amazon’s best selling eBooks? Best sellers’ lists rarely feature eight pages of watered down analysis of a search vendor with some soul bonding with the outstanding Fast Search & Transfer operation. How many folks visiting the digital WalMart buy $3,500 reports with my name on them?

Er, zero. So what’s the disconnect between basic data about what sells on Amazon, issuing appropriate contractual documents, and selling research with my name and two of my goslings on the $3,500, eight page document. That’s brilliant data analysis for sure.

The write up explains:

Businesses want to use data to understand customers, but they can’t do that without harnessing insights and consistently turning data into effective action.

That sort of makes sense except that the company which owns Computerworld, under the keen-eyed Dave Schubmehl, appeared to ignore this step when trying to sell a report with my name on it to the Amazon faithful. Do the folks at Computerworld and the company’s various knowledge properties connect data with their colleagues’ decisions?

Yahoo: Semantic Search Is the Future

August 16, 2015

I love it when Yahoo explains the future of search. The Xoogler has done the revisionism thing and shifted from Yahoo as a directory built by silly humanoids to a leader in search. Please, do not remember that Yahoo bought Inktomi in 2002 and then rolled out a wild and crazy search system in cahoots with IBM in 2006. (By the way, that search solution brought my IBM multi cpu, DASD equipped, RAM stuffed server to its knees. At least, the “free” software installed.)

Now to business: I read “The Future of Search Relies on Semantic Technologies.” For me, semantic technologies have been part of search for many years. But never mind reality. Let’s get to the Reddi-wip in the Yahoo confection.

Yahoo asserts:

Search companies are thus investing in information extraction and data fusion, as well as more and more advanced question-answering capabilities on top of the collected information. The need for these technologies is only increasing with mobile search, where providing results as ten blue links leads to a very poor user experience.

I would point out that as lousy as blue links are, these links produce about $60 billion a year for the Alphabet Google thing and enough zeros for the Microsoft wizards to hang on to its online advertising business even as it loses enthusiasm for other aspects of the Bing thing.

Yahoo adds:

We are a consumer internet company, so for us there is little difference between our internal and external representations.

My comment is a simple question, “What the heck is Yahoo saying?”

I also highlighted this semantic gem:

At Yahoo Labs, we work in advancing the sciences that underlie these approaches, i.e. Natural Language Processing, Information Retrieval and the Semantic Web.

I like the notion of Yahoo advancing science. I wonder if these advances will lead to advances in top line revenue, stabilizing management, and producing search results that are sort of related to the query.

Watson: The PR Blitz Continues

July 28, 2015

I know that IBM is trying to reverse 13 quarters of revenue decline. I know that most of the firm’s business units are struggling to hit their numbers. I know that IBM’s loyal employees are doing their best to belt out the IBM song “Ever Onward” in perfect harmony.

If you are not familiar with the lyrics, you can read the words at this link on the IBM Web site, which unlike the dev ops pages are still online:

EVER ONWARD — EVER ONWARD!

That’s the spirit that has brought us fame!

We’re big, but bigger we will be

We can’t fail for all can see

That to serve humanity has been our aim!

Our products now are known, in every zone,

Our reputation sparkles like a gem!

We’ve fought our way through — and new

Fields we’re sure to conquer too

For the EVER ONWARD I.B.M.

Goodness, I am tapping my foot just reading the phrase “Our reputation sparkles like a gem!”

And I don’t count the grinches who complain at EndicottAlliance.org like this:

Comment 07/27/15:

Job Title: IT Specialist

Location: Rochester MN

CustAcct: Various

BusUnit: Cloud

Message: I was forced out/bullied out through bad PBC rating/threats of PIP. I left voluntarily a few months back, rather than waiting for the inevitable layoff (since my 2014 rating was a 3, I would have probably been let go with no package). Once I got my appraisal in January, I started looking around and found another job that pays about the same as my band 10 IBM salary – and I am evaluating several other offers as we speak. I truly feel for the victims of yet another round of layoffs. But I don’t quite understand why some find it “shocking” and “unexpected” that IBM gets rid of them. Your CEO has publicly declared that many of you – especially those in the services organizations – are nothing more than “empty calories.” She went on record with those words. What do you expect? Either you organize or you better start looking for something else.

I pay attention to the “3 Lessons IBM’s Watson Can Teach Us about Our Brains’ Biases.” The write up explains:

Cognitive computing is transforming the way we work.

Enterprise Search and the Mythical Five Year Replacement Cycle

July 9, 2015

I have been around enterprise search for a number of years. In the research we did in 2002 and 2003 for the Enterprise Search Report, my subsequent analyses of enterprise search both proprietary and open source, and the ad hoc work we have done related to enterprise search, we obviously missed something.

Ah, the addled goose and my hapless goslings. The degrees, the experience, the books, and the knowledge had a giant lacuna, a goose egg, a zero, a void. You get the idea.

We did not know that an enterprise licensing an open source or proprietary enterprise search system replaced that system every 60 months. We did document the following enterprise search behaviors:

- Users express dissatisfaction about any installed enterprise search system. Regardless of vendor, anywhere from 50 to 75 percent of users find the system a source of dissatisfaction. That suggests that enterprise search is not pulling the hay wagon for quite a few users.

- Organizations, particularly the Fortune 500 firms we polled in 2003, had more than five enterprise search systems installed and in use. The reason for the grandfathering is that each system had its ardent supporters. Companies just grandfathered the system and looked for another system in the hopes of finding one that improved information access. No one replaced anything was our conclusion.

- Enterprise search systems did not change much from year to year. In fact, the fancy buzzwords used today to describe open source and proprietary systems were in use since the early 1980s. Dig out some of Fulcrum’s marketing collateral or the explanation of ISYS Search Software from 1986 and look for words like clustering, automatic indexing, semantics, etc. A short cut is to read some of the free profiles of enterprise search vendors on my Xenky.com Web site.

I learned about a white paper, which is 21st century jargon for a marketing essay, titled “Best Practices for Enterprise Search: Breaking the Five-Year Replacement Cycle.” The write up comes from a company called Knowledgent. The company describes itself this way on its Who We Are Web page:

Knowledgent [is] a precision-focused data and analytics firm with consistent, field-proven results across industries.

The essay begins with a reference to Lexis, which along with Don Wilson (may he rest in peace) and a couple of colleagues founded. The problem with the reference is that the Lexis search engine was not an enterprise search and retrieval system. The Lexis OBAR system (Ohio State Bar Association) was tailored to the needs of legal researchers, not general employees. Note that Lexis’ marketing in 1973 suggested that anyone could use the command line interface. The OBAR system required content in quite specific formats for the OBAR system to index it. The mainframe roots of OBAR influenced the subsequent iterations of the LexisNexis text retrieval system: Think mainframes, folks. The point is that OBAR was not a system that was replaced in five years. The dog was in the kennel for many years. (For more about the history of Lexis search, see Bourne and Hahn, A History of Online information Services, 1963-1976. By 2010, LexisNexis had migrated to XML and moved from mainframes to lower cost architectures. But the OBAR system’s methods can still be seen in today’s system. Five years. What are the supporting data?

The white paper leaps from the five year “assertion” to an explanation of the “cycle.” In my experience, what organizations do is react to an information access problem and then begin a procurement cycle. Increasingly, as the research for our CyberOSINT study shows, savvy organizations are looking for systems that deliver more than keyword and taxonomy-centric access. Words just won’t work for many organizations today. More content is available in videos, images, and real time almost ephemeral “documents” which can difficult to capture, parse, and make findable. Organizations need systems which provide usable information, not more work for already overextended employees.

The white paper addresses the subject of the value of search. In our research, search is a commodity. The high value information access systems go “beyond search.” One can get okay search in an open source solution or whatever is baked in to a must have enterprise application. Search vendors have a problem because after decades of selling search as a high value system, the licensees know that search is a cost sinkhole and not what is needed to deal with real world information challenges.

What “wisdom” does the white paper impart about the “value” of search. Here’s a representative passage:

There are also important qualitative measures you can use to determine the value and ROI of search in your organization. Surveys can quickly help identify fundamental gaps in content or capability. (Be sure to collect enterprise demographics, too. It is important to understand the needs of specific teams.) An even better approach is to ask users to rate the results produced by the search engine. Simply capturing a basic “thumbs up” or “thumbs down” rating can quickly identify weak spots. Ultimately, some combination of qualitative and quantitative methods will yield an estimate of search, and the value it has to the company.

I have zero clue how this set of comments can be used to justify the direct and indirect costs of implementing a keyword enterprise search system. The advice is essentially irrelevant to the acquisition of a more advanced system from an leading edge next generation information access vendor like BAE Systems (NetReveal), IBM (not the Watson stuff, however), or Palantir. The fact underscored by our research over the last decade is tough to dispute: Connecting an enterprise search system to demonstrable value is a darned difficult thing to accomplish.

It is far easier to focus on a niche like legal search and eDiscovery or the retrieval of scientific and research data for the firm’s engineering units than to boil the ocean. The idea of “boil the ocean” is that a vendor presents a text centric system (essentially a one trick pony) as an animal with the best of stallions, dogs, tigers, and grubs. The spam about enterprise search value is less satisfying than the steak of showing that an eDiscovery system helped the legal eagles win a case. That, gentle reader, is value. No court judgment. No fine. No PR hit. A grumpy marketer who cannot find a Web article is not value no matter how one spins the story.

Enterprise Search: The Last Half of 2015

June 16, 2015

I saw a link this morning to an 11 month old report from an azure chip consulting firm. You know, azure chip. Not a Bain, BCG, Booz Allen, or McKinsey which are blue chip firms. A mid tier outfit. Business at the Boozer is booming is the word from O’Hare Airport, but who knows if airport gossip is valid.

Which enterprise search vendor will come up a winner in December 2015?

What is possibly semi valid are analyses of enterprise search vendors. The “Magic Quadrant for Enterprise Search” triggered some fond memories of the good old days in 2003 when the leaders in enterprise search were brands or almost brands. You probably recall the thrilling days of these information retrieval leaders:

- Autonomy, the math oriented outfit with components names like neuro linguistic programming and integrated data operating layer and some really big name customers like BAE

- Convera, formerly Excalibur with juice from ConQuest (developer by a former Booz, Allen person no less)

- Endeca, the all time champ for computationally intensive indexing

- Fast Search & Transfer, the outfit that dumped Web search in order to take over the enterprise search sector

- Verity, ah, truth be told, this puppy’s architecture ensured plenty of time to dash off and grab a can of Mountain Dew.

In 2014, if the azure chip firm’s analysis is on the money, the landscape was very different. If I understand the non analytic version of Boston Consulting Group’s matrix from 1970, the big players are:

- Attivio, another business intelligence solution using open source technology and polymorphic positioning for the folks who have pumped more than $35 million into the company. One executive told me via LinkedIn, that the SEC investigation of an Attivio board member had zero impact on the company. I like the attitude. Bold.

- BA Insight, a business software vendor focused on making SharePoint somewhat useful and some investors with deepening worry lines

- Coveo, a start up which is nudging close to a decade in age, and more than $30 million in venture backing. I wonder if those stakeholders are getting nervous.

- Dassault Systèmes, the owner of Exalead, who said in the most recent quarterly report that the company was happy, happy, happy with Exalead but provided no numbers and no detail about the once promising technology

- Expert System, an interesting company with a name that makes online research pretty darned challenging

- Google, ah, yes, the proud marketer of the ever thrilling Google Search Appliance, a product with customer support to make American Airlines jealous

- Hewlett Packard Autonomy, now a leader in the acrimonious litigation field

- IBM, ah, yes, the cognitive computing bunch from Armonk. IBM search is definitely a product that is on everyone’s lips because the major output of the Watson group is a book of recipes

- IHS, an outfit which is banking on its patent analysis technology to generate big bucks in the Goldmine cellophane

- LucidWorks (Really?), a repackager of open source search and a distant second to Elastic (formerly Elasticsearch, which did not make the list. Darned amazing to me.)

- MarkLogic, a data management system trying to grow with a proprietary XML technology that is presented as search, business intelligence, and a tool for running a restaurant menu generation system. Will MarkLogic buy Smartlogic? Do two logics make a rational decision?

- Mindbreeze, a side project at Fabasoft which is the darling of the Austrian government and frustrated European SharePoint managers

- Perceptive Software, which is Lexmark’s packaging of ISYS Search Software. ISYS incorporates technology from – what did the founder tell me in 2009? – oh, right, code from the 1980s. Might it not be tough to make big bucks on this code base? I have 70 or 80 million ideas about the business challenge such a deal poses

- PolySpot, like Sinequa, a French company which does infrastructure, information access, and, of course, customer support

- Recommind, a legal search system which has delivered a down market variation of the Autonomy-type approach to indexing. The company is spreading its wings and tackling enterprise search.

- Sinequa, another one of those quirky French companies which are more flexible than a leotard for an out of work acrobat

But this line up from the azure chip consulting omits some companies which may be important to those looking for search solutions but not so much for azure chip consultants angling for retainer engagements. Let me highlight some vendors the azure chip crowd elected to ignore:

An Enterprise Search Mini Case: LucidWorks and Its Accelerating Mission

June 11, 2015

I read “Lucidworks Accelerates Product Focused Mission with Major Fusion Upgrades.” LucidWorks (Really?)—né Lucid Imagination—appears to be working on products. (Note that the company names appears in different ways: “Lucidworks” with variants “LucidWorks”, “Lucid Works,” and “lucidworks”.)

Lucidworks wants to accelerate its mission. Will this be a quick and easy task?

Flashback in time. Lucid Imagination was founded in 2007. You can read about the vision of the company in interviews with these Lucid (no pun intended) executives:

- Marc Krellenstein, formerly Northern Light and one of the founders of Lucid Imagination, March 17, 2009

- Brian Pinkerton, formerly, December 21, 2010, possibly Amazon?

- Paul Doscher, formerly with Exalead, April 16, 2012

- Miles Kehoe, formerly New Idea Engineering, January 29, 2013, now a consultant

- Mark Bennett, formerly New Idea Engineering, March 4, 2014

These interviews make clear the difficult journey that Lucid Imagination took. (What is interesting is that Lucid’s principal competitor was Elasticsearch, now Elastic. That company came from obscurity to the go-to provider of open source search. To be fair, Shay Bannon, founder of Elastic, had compiled considerable experience with the Compass open source search system.)

Why did I cover Lucid in five interviews?

The reason is that open source search appeared to be the salve to soothe the wounds inflicted by proprietary search system vendors. Satisfaction with search was declining. Users were disaffected with high profile proprietary brands. The community approach addressed, in part, the brutal research, development, and customer support costs which search drags to each meeting with stakeholders.

Lucid had a lead; Elastic benefited. Lucid seeks a focus; Elastic is serving customers. Lucid would be an excellent business school case study, ranking at the top along with the Hewlett Packard Autonomy search situation and the Fast Search criminal charges matter. That is rarified case study company.

In the interviews cited above, it is clear that Lucid embraced Solr and made an attempt to emulate the full featured approach to content processing exemplified by Autonomy and Fast Search & Transfer. Elastic, on the other hand, took a more direct approach, relying on Lucene for the heavy lifting, and narrowing its focus to tools which were almost utilitarian. Want to search a log file? Go with Elastic.

The other key difference is the lack of managerial drama at Elastic. Elastic’s management team appears, at least to this observer in Kentucky, as stable. Lucid, on the other hand, has seen the departure of founders early in the company’s history. Presidents arrived and departed. Marketers appeared and disappeared. Major committers joined and then jumped ship; for example, Brian Pinkerton ended up at Amazon, working on its search product. Yonik Seeley also left to start his own search company Heliosearch. Dr. Krellenstein went from strong supported of Lucid to a disaffected founded. He quit.

As recently as September 2014, Lucid Works featured in “Trouble at LucidWorks: Lawsuits, Lost Deals, and Layoffs Plague the Search Startup Despite Funding.” The headline makes several points. First, LucidWorks has ingested more than $40 million, which puts it on a par with Attivio and Coveo in the money department. But Elastic garnered about $70 million at about the same time. The headline also reveals the disjunctions among managers, regardless of which president was on watch. And, the headline focuses on the point that it is a search vendor, which is not in my opinion a particularly magnetic positioning for software.

According to the “Trouble at LucidWorks” article The Guardian and Nordstrom’s abandoned Lucid’s software. The less than flattering Venture Beat story added:

The situation seems to have worsened following shakeups in the sales team, leaving young salespeople inexperienced in the enterprise-software game trying to win deals. “I don’t think any of the sales team hits (their) number except one guy,” said a former employee. And that one guy has resorted to “dropping his pants,” as the sales expression goes, promising to significantly chop the price of a service if his lead commits to buying right away, a different former employee said. The sales goals aren’t increasing. The revenue target for the year is $12 million, right in line with last year, that former employee said. And it doesn’t help that LucidWorks has fumbled with partnerships it was trying to get in place. It was working on alliances with Amazon Web Services, Intel, and Splunk, one former employee told VentureBeat. “Will [Hayes] imploded that with comments he made in the final agreement,” that former employee said of one partnership. And after Hayes stepped up as chief executive in June, he’s laid off people in marketing, sales, and business development. On the technology side of the company, meanwhile, employees have missed deadlines for shipping software to customers, month after month, another former employee said. Outside the office, the company has other distractions — in court, to be exact. Mike Moody, a former senior vice president of engineering at LucidWorks who was terminated in December, sued LucidWorks and certain executives in February for unlawful termination, according to documents submitted to the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California. LucidWorks is also ensnared in a case it filed against Seeley, one of its founders, in the Superior Court of California, San Mateo County. “This is a case about double-dealing on an employer, which arises from the secretive founding and launching of the company Heliosearch by Yonik Seeley before his resignation from his former employer LucidWorks in October 2013,” the complaint begins. “Unknown to LucidWorks, while Seeley was still employed by LucidWorks, he simultaneously was working directly against LucidWorks’ interests by developing and promoting his new venture Heliosearch as a competing alternative to LucidWorks.”

The Future of Enterprise and Web Search: Worrying about a Very Frail Goose

May 28, 2015

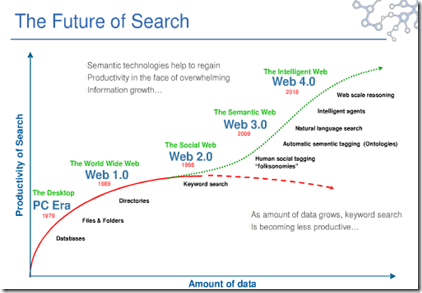

For a moment, I thought search was undergoing a renascence. But I was wrong. I noted a chart which purports to illustrate that the future is not keyword search. You can find the illustration (for now) at this Twitter location. The idea is that keyword search is less and less effective as the volume of data goes up. I don’t want to be a spoil sport, but for certain queries key words and good old Boolean may be the only way to retrieve certain types of information. Don’t believe me. Log on to your organization’s network or to Google. Now look for the telephone number of a specific person whose name you know or a tire company located in a specific city with a specific name which you know. Would you prefer to browse a directory, a word cloud, a list of suggestions? I want to zing directly to the specific fact. Yep, key word search. The old reliable.

But the chart points out that the future is composed of three “webs”: The Social Web, the Semantic Web, and the Intelligent Web. The dates for the Intelligent Web appears to be 2018 (the diagram at which I am looking is fuzzy). We are now perched half way through 2015. In 30 months, the Intelligent Web will arrive with these characteristics:

- Web scale reasoning (Don’t we have Watson? Oh, right. I forgot.)

- Intelligent agents (Why not tap Connotate? Agents ready to roll.)

- Natural language search (Yep, talk to your phone How is that working out on a noisy subway train?)

- Semantics. (Embrace the OWL. Now.)

Now these benchmarks will arrive in the next 30 months, which implies a gradual emergence of Web 4.0.

The hitch in the git along, like most futuristic predictions about information access, is that reality behaves in some unpredictable ways. The assumption behind this graph is “Semantic technology help to regain productivity in the face of overwhelming information growth.”