An Idea for American Top Dogs?

June 14, 2021

My hunch is that the cyber security breaches center of flaws in Microsoft Windows. The cyber security vendors, the high priced consultants, and even the bad actors renting their services to help regular people are mostly ineffectual. The rumors about a new Windows are interesting. The idea that Windows 10 will not be supported in the future is less interesting. I interpret the information as a signal that Microsoft has to find a fix. Marketing, a “new” Windows, and mucho hand waving will make the problem go away. But will it? Nope. Law enforcement, intelligence professionals, and security experts are operating in reactive mode. Something happens; people issue explanations; and the next breach occurs. Consider gamers. These are not just teenies. Nope. Those trying to practice “adulting” are into these escapes. TechRepublic once again states the obvious in “Fallout of EA Source Code Breach Could Be Severe, Cybersecurity Experts Say.” Here’s an extract:

The consequences of the hack could be existential, said Saryu Nayyar, CEO of cybersecurity firm Gurucul. “This sort of breach could potentially take down an organization,” she said in a statement to TechRepublic. “Game source code is highly proprietary and sensitive intellectual property that is the heartbeat of a company’s service or offering. Exposing this data is like virtually taking its life. Except that in this case, EA is saying only a limited amount of game source code and tools have been exfiltrated. Even so, the heartbeat has been interrupted and there’s no telling how this attack will ultimately impact the life blood of the company’s gaming services down the line.”

I like that word “existential.”

I want to call attention to this story in Today Online: “Japan’s Mizuho Bank CEO to Resign after Tech Problems.” Does this seem like a good idea? To me, it may be appropriate in certain situations. A new top dog at Microsoft would have a big job to do for these reasons:

- New or changed software introduces new flaws and exploitable opportunities.

- New products with numerous new features increase the attack surface; for example, Microsoft Teams, which is demonstrating the Word method of adding features to keep wolves like Zoom, Google, and others out of the hen house.

- A flood of marketing collateral, acquisitions, and leaks about a a new Windows are possible distractions for a very uncritical but influential observers.

But what’s the method in the US. Keep ‘em on the job. How is that working?

Stephen E Arnold, June 14, 2021

More Google Management Methodology in Action: Speak Up and Find Your Future Elsewhere

June 11, 2021

“Worker Fired for Questioning Woke Training” presents information that Taras Kobernyk (now a Xoogler) was fired for expressing his opinion about specialized training. The “training” was for equity training. The former employee of the online ad company was identified as an individual who was not Googley. The Fox News segment aired on Wednesday, June 9, 2021 and was online at this link as of 10 am on June 11, 2021. The story was recycled at “Tucker Carlson Interviews Former Google Employee Who Was Fired after Questioning Woke Training Programs.” Here’s a quote from that write up:

“I was told that certain sections of the document were questioning experiences with people of color or criticizing fellow employees, or even that I was using the word “genetics” in the racial context.”

Some pundit once said, “Any publicity is good publicity.” Okay. Who would have thought that a large company’s human resources’ management decisions would carry another Timnit Gebru placard? Dare I suggest a somewhat sophomoric approach may be evident in these personnel moves? Yes, high school science club DNA traces are observable in this case example if it is indeed true.

Stephen E Arnold, June 11, 2021

Two Write Ups X Ray High Tech Practices Ignoring Management Micro Actions

June 9, 2021

This morning I noted two widely tweeted write ups. The first is Wired’s “What Really Happened When Google Ousted Timnit Gebru”; the second is “Will Apple Mail Threatened the Newsletter Boom?” Please, read both source documents. In this post I want to highlight what I think are important omissions in these and similar “real journalism” analyses. Some of the information in these two essays is informative; however, I think there is an issue which warrants commenting upon.

The first write up purports to reveal more about the management practices which created what is now a high profile case example of management practices. How many other smart software researchers have become what seems to be a household name among those in the digital world? Okay, Bill Gates. That’s fair. But Mr. Bill is a male, and males are not exactly prime beef in the present milieu. Here’s a passage I found representative of the write up:

Beyond Google, the fate of Timnit Gebru lays bare something even larger: the tensions inherent in an industry’s efforts to research the downsides of its favorite technology. In traditional sectors such as chemicals or mining, researchers who study toxicity or pollution on the corporate dime are viewed skeptically by independent experts. But in the young realm of people studying the potential harms of AI, corporate researchers are central.

What I noted is the “larger.” But what is missed is the Cinemascope story of a Balkanized workforce and management disconnectedness. I get the “larger”, but the story, from my point of view, does not explore the management methods creating the situation in the first place. It is these micro actions that create the “larger” situation in which some technology outfits find themselves mired. These practices are like fighting Covid with a failed tire on an F1 race car.

The second write — “Will Apple Mail Threaten the Newsletter Boom?” — up tackles the vendor saying one thing and doing a number of quite different “other things.” The write up is unusual because it puts privacy front and center. I noted this statement:

All that said, I can’t end without pointing out the ways in which Apple itself benefits from cracking down on email data collection. The first one is obvious: it further burnishes the company’s privacy credentials, part of an ongoing and incredibly successful public-relations campaign to build user trust during a time of collapsing faith in institutions.

Once again the big picture is privacy and security. From my point of view, Apple is taking steps to make certain it can do business with China and Russia. Apple wants to look out for itself, and it is conducting an effective information campaign. The company uses customers, “real journalists,” and services which provide covers for other actions. Like the story about Dr. Gebru and Google, this type of Apple write up misses the point of the great privacy trope: Increased revenues at the expense of any significant competitor. In this particular case, certain “real journalists” may have their financial interests suppressed. Management micro actions create collateral damage. Perhaps focusing on the micro actions in a management context will explain what’s happening and why “real journalists” are agitated?

What’s being missed? Stated clearly, the management micro actions that are fanning the flames of misunderstanding.

Stephen E Arnold, June 9, 2021

Amazon: Possibly Going for TikTok Clicks?

June 8, 2021

I don’t know if this story is true. For all I know, this could be the work of some TikTok wannabes who need clicks. Perhaps a large competitor of the online bookstore set up this incident? Despite my doubts, I find the information in “Video Shows Amazon Driver Punching 67-Year-Old Woman Who Reportedly Called Her a B*tch.” The main idea is that a person who could fight Logan Paul battled a 67 year old woman. That’s no thumbtyper. That’s a person who writes with a pencil on paper. The outrage.

According the the “real” news report:

SHOCKING VIDEO shows an Amazon Driver giving a 67 year old Castro Valley woman a beat down after words were exchanged. 21 year old woman arrested by Alco Sherriff…who says suspect claims self defense.

Yes, it is clear that the 67 year old confused the Amazon professional with a boxing performer. After a “verbal confrontation,” the individuals turned to the sweet science.

Pretty exciting and the event was captured on video and appears to be streaming without problems. That’s something that could not be said about the Showtime exhibition or Amazon and Amazon Twitch a few hours ago. (It is Tuesday, June 8, 2021, and Amazon was a helpless victim of another feisty Internet athlete.)

Exciting stuff. Will there be a rematch?

Stephen E Arnold, June 8, 2021

Google: Do What We Say, Ignore What We Do, Just Heel!

June 8, 2021

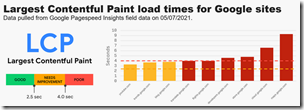

If this Reddit diagram is on the money, we have a great example of how Google management goes about rule making. The post is called “Google Can’t Pass Its Own Page Speed Test.” The post was online on June 5, 2021, but when Beyond Search posts this short item, that Reddit post may be tough to find. Why? Oh, because.

- There are three grades Dearest Google automatically assigns to those who put content online. There are people who get green badges (just like in middle school). There are people who warrant yellow badges (no, I won’t mention a certain shop selling cloth patches in the shape of pentagons with pointy things), and red badges (red, like the scarlet letter, and you know what that meant in Puritan New England a relatively short time ago).

Notice that these Google sites get the red badge of high school science club mismanagement recognition:

- Google Translate

- Google’s site for its loyal and worshipful developers

- Google’s online store where you can buy tchotchkes

- The Google Cloud which has dreams of crushing the competitors like Amazon and Microsoft into non-coherent photons

- Google Maps which I personally find almost impossible to use due to the effort to convert a map into so much more than a representation of a territory. Perhaps a Google Map is not the territory? Could it be a vessel for advertising?

There are three Google services which get the yellow badge. I find the yellow badge thing very troubling. Here these are:

- YouTube, an outstanding collection of content recommended by a super duper piece of software and a giant hamper for online advertising of Grammarly, chicken sandwiches, insurance, and so much more for the consumers of the world

- Google Trends. This is a service which reveals teeny tiny slice of the continent of data it seems the Alphabet Google thing possesses

- The Google blog. That is a font of wisdom.

Observations:

- Like Google’s other mandates, it appears that those inside the company responsible for Google’s public face either don’t know the guidelines or simply don’t care.

- Like AMP, this is an idea designed to help out Google. Making everyone go faster reduces costs for the Google. Who wants to help Google reduce costs? I sure do.

- Google’s high school science club management methods continue to demonstrate their excellence.

What happens if a non Google Web site doesn’t go fast? You thought you got traffic from Google like the good old days, perhaps rethink that assumption?

Stephen E Arnold, June 8, 2021

Google Management Methods: A Partial CAT scan

June 8, 2021

The document “Thoughts on Cadence” is online as of June 7, 2021, at 6 am US Eastern. If you are a fan of management thrillers, you will want to snag this 14 page X Ray at www.shorturl.at/dgCY6 or maybe www.shorturl.at/cdBE2. (No guarantee how long the link will be valid. Because… Google, you know.)

“Cadence” was in the early 2000s, popular among those exposed to MBA think. The idea was that a giant, profit centric organization was organized. Yep, I know that sounds pretty crazy, but “cadence” implied going through training, getting in sync, and repeating the important things. Hut one two three four or humming along to a catchy tune crafted by Philip Glass. Thus, the essay by a person using the identifier Shishir Mehrotra, who is positioned as a Xoogler once involved in the YouTube business. A book may be forthcoming with the working title Rituals of Great Teams. I immediately thought of the activities once conducted at Templo Mayor by the fun loving Aztecs.

I am not going to walk through the oh, so logical explanation of the Google Management Method’s YouTube team. I want to highlight the information in the Tricks section. With such a Campbell soup approach to manufacturing great experiences, these magical manipulations reveal more of the Google method circa 2015. Procedures can change is six years. Heck, this morning, Google told me I used YouTube too much. I do upload a video every two weeks, so now “that’s enough” it seems.

Now to the tricks.

The section is short and it appears these are designed to be “productivity techniques.” It is not clear if the tricks are standard operating procedure, but let’s look at these six items.

First, one must color one’s calendar.

Second, have a single goal for each meeting.

Third, stand up and share notes and goals.

Fourth, audit the meetings.

Fifth, print your pre reading.

Sixth, have a consistent personal schedule.

Anyone exposed to meetings at a Google type of company knows that the calendar drives the day. But what happens when people are late, don’t attend, or play with their laptops and mobile phones during the meeting. Plus, the “organizer” often changes the meeting because a more important Google type person adds a meeting to the organizer’s calendar. Yep, hey, sorry really improves productivity. In my limited experience, none of these disruptions ever occur. Nope. Never. Consequently, the color of the calendar box, the idea of the meeting itself, and the concept of a consistent personal schedule are out the window.

Now the single goal thing is interesting. In Google type companies, there are multiple goals because each person in the meeting has an agenda: A lateral move or arabesque to get on a hot project, get out of the meeting to go get a Philz coffee, or nuke the people in the meeting who don’t understand the value of ethical behavior.

The print idea is interesting. In my experience, I am not sure printed material is as plentiful in meetings as it was when I worked at some big outfits. Who knows? Maybe 2015 thumb typers, GenXers, and Millennials did embrace the paper thing.

Thus, the tricks seem like a semi-formed listicle. With management precepts like the ones in the “Cadence” document, I can see why the Google does a bang up job on human resource management, content filtering, and thrilling people with deprecated features. Sorry, Gran, your pix of the grandchildren are gone now but the videos of the kids romping in the backyard pool are still available on YouTube.

Great stuff! Productivity come alive.

Stephen E Arnold, June 8, 2021

Misunderstanding the Logic of Rank-and-Yank 2021 Style

June 7, 2021

Many years ago when I worked at a big time consulting firm, GE was a good customer. Anecdotes about Neutron Jack were frequent. After departing the estimable firm, Neutron became a management guru, an author, and an esteemed business luminary. One comment about Neutron has remained with me for more than 40 years was:

Stack and rank or the more upscale vitality curve.

My fave for this concept which the big time consulting firm enthusiastically embraced was “rank and yank.”

“Amazon’s Controversial ‘Hire to Fire’ Practice Reveals a Brutal Truth About Management” is adrift from Neutron Jack’s method. In fact, the write up is critical of Amazon’s implementation of this logical and realistic practice. Not everyone is intellectually or socially equivalent. In a profit making entity, it is necessary to cultivate an environment in which winners win. Losers — that is, who don’t perform either in terms of meeting objectives or socially in terms of making colleagues love them like a puppy — have an opportunity to find their future elsewhere.

The write up states with little awareness of the rich principles of Neutron Jack:

Amazon managers are hiring people they otherwise wouldn’t, or shouldn’t, just so they can later fire them to hit their goal. That completely defeats the point since–if the metric is based on sound business principles–there are people keeping their job who shouldn’t, at the expense of the sacrificial lamb.

The write up does not understand the dynamics of a big time, 21st century profit machines. Athletes cheat. Honest executives cheat on their taxes. Ministers in Kentucky find interaction with some congregation members the best thing ever.

The consequence of hiring to fire and Neutron’s rank-and-yank approach is to further one’s own success. Does the reader of the Inc. article think for a New York minute that an executive at a monopoly like company is into public good, doing what’s right for a fuzzy idea like ethical behavior, or being honest. Even the glittery Apple executive Tim Apple revealed that the app store 30 percent was to enrich Apple, not help the gamer.

Net net: Please, connect with reality in 2021.

Stephen E Arnold, June 7, 2021

Google: The High School Science Club Management Method Cracks Location Privacy

June 2, 2021

How does one keep one’s location private? Good question. “Apple Is Eating Our Lunch: Google Employees Admit in Lawsuit That the Company Made It Nearly Impossible for Users to Keep Their Location Private” explains:

Google continued collecting location data even when users turned off various location-sharing settings, made popular privacy settings harder to find, and even pressured LG and other phone makers into hiding settings precisely because users liked them, according to the documents.

The fix. Enter random locations in order to baffle the high school science club whiz kids. The write up explains:

The unsealed versions of the documents paint an even more detailed picture of how Google obscured its data collection techniques, confusing not just its users but also its own employees. Google uses a variety of avenues to collect user location data, according to the documents, including WiFi and even third-party apps not affiliated with Google, forcing users to share their data in order to use those apps or, in some cases, even connect their phones to WiFi.

Interesting. The question is, “Why?”

My hunch is that geolocation is a darned useful item of data. Do a bit of sleuthing and check out the importance of geolocation and cross correlation on policeware and intelware solutions. Marketing finds the information useful as well. Does Google have a master plan? Sure, make money. The high school science club wants to keep the data flowing for three reasons:

First, ever increasing revenues are important. Without cash flow, Google’s tough-to-control costs could bring down the company. Geolocation data are valuable and provide a kitting needle to weave other items of information into a detailed just-for-you quilt.

Second, Amazon, Apple, and Facebook pose significant threats to the Google. Amazon is, well, doing its Bezos bulldozer thing. Apple is pushing its quasi privacy campaign to give “users” control. And Facebook is unpredictable and trying to out Google Google in advertising and user engagement. These outfits may be monopolies, but monopolies have to compete so high value data become the weaponized drones of these business wars.

Third, Google’s current high school management approach is mostly unaware of how the company gathers data. The systems and methods were institutionalized years ago. What persists are the modules of code which just sort of mostly do their thing. Newbies use the components and the data collection just functions. Why fix it if it isn’t broken. That assumes that someone knows how to fiddle with legacy Google.

Net net: Confusion. What high school science club admits to not having the answers? I can’t name one, including my high school science club in 1958. Some informed methods are wonderful and lesser being should not meddle. I read the article and think, “If you don’t get it, get out.”

Stephen E Arnold, June 1, 2021

Google: More Personnel Excitement

June 1, 2021

I am not too keen on what used to be called human resources. I am not sure I liked being a “resource” like sand or lignite. I once wrote a report about “sherm”. Was I surprised. The “word” was the way personnel professionals pronounced the estimable trade association Society for Human Resource Management. SHRM became sherm to those in the know. I did the report; got paid; and decided to not think about personnel again. Until I read “Over 10,000 Women Are Suing Google over Gender Pay Disparity.” Now that’s a personnel story which is almost up to the level of the Timnit Gebru matter.

According to the write up:

Four women who worked at Google have won class-action status to proceed with their gender pay disparity lawsuit, reports Bloomberg. The latest ruling in the protracted legal battle means the suit can now apply to 10,800 women who held various positions at the tech giant since 2013. Those affected represent a broad cross-section of vocations including engineers, program managers, salespeople and at least one preschool teacher. The women, who are seeking more than $600 million in damages, allege Google violated the California Equal Pay Act by paying them less than their male counterparts, promoting them slowly and less frequently.

I have used the phrase “high school science club management methods” or HSSCMM or H2SC2M to capture the approach some Google managers take to the personnel thing. If the information in the article is accurate, it would appear that Google had institutionalized pay disparity. That’s something my high school science club would have done for sure.

My thought is that Alphabet Google may want to check out the information on the SHRM Web site. I clicked on the Compensation tab and spotted a number of articles about employee pay. There’s an entry for “Using AI in Comp Decisions? Here’s How to Build Trust.” That write up seems germane. It mentions artificial intelligence, and based on the recent Google conference, smart software is a big deal at the Google. The write up mentions “trust.” That’s important when visiting via Google’s Zoom clone with prospective female hires at big time universities.

Perhaps Google should pull up roots and relocate to a country which does not fiddle around with the equality notion? Can a high school science club just pick up and head to such a place? Sure. High school science thinkers (regardless of age) can come up with absolutely brilliant solutions that seem logical to them. Example: Buying Motorola, Orkut, solving death, etc.

It’s sherm. Remember when you sign up for an online equality in compensation course. Sherm and 657175616c697479.

Stephen E Arnold, May 28, 2021

Great Moments in Management: Rolfing and AmaZen

May 31, 2021

Happy holiday, everyone. I spotted two fascinating examples of message control and management this morning. The first is the Daily Dot “real” news about an Amazon driver getting into Rolfing. “Weekend Update: People Feel Sorry for Amazon Driver Caught Screaming from Truck” reports:

One of the TikTok videos in question features an Amazon driver screaming at the top of his lungs as he makes his way down the street in the delivery truck. His apparent distress while on the clock has sympathetic viewers calling for higher wages and better working conditions for all Amazon employees.

Yep, TikTok. Who can believe that content engine? Probably some of the deep thinkers who absorb information in 30 second chunks. I think of TikTok as a “cept ejector.” Yes, like Rolfing, “cepts” were a thing years ago. Rusty on Rolfing? Check out this link.

The second mesmerizer is described in “Introducing the “AmaZen” Booth, a Box Designed for Convenient, On-Site Worker Breakdowns.” This coffin sized object looks like a coffin. The story reports that an Amazon wizard said:

“With AmaZen, I wanted to create a space that’s quiet, that people could go and focus on their mental and emotional well-being,” Brown explains over footage of an employee entering what looks like a porta potty decorated with pamphlets, a computer, some sad little plants, and a tiny fan. She continues, calling the overgrown iron maiden a place to “recharge the internal battery” by checking out “a library of mental health and mindful practices.”

What do screaming employees and a work environment requiring a coffin sized Zen booth suggest? Many interesting things I wager.

Management excellence in action. Is this something a high school science club might set up as a prank?

Stephen E Arnold, May 31, 2021