Quality Defined: Just Two Ways?

August 25, 2022

I am not sure what to make of “The Two Types of Quality.” A number of years ago I was in Osaka and Tokyo to deliver several lectures about commercial databases. The topic had to be narrowed, so I focused on the differences between a commercially successful database like those produced by the Courier Journal & the Louisville Times, the Petroleum Institute, and ERIC, among a handful of other must-have professional-operated databases. I explained that database quality could be defined by technical requirements; for example, timeliness of record updating, assigning a specific number of index terms from a subject matter expert developed and maintained controlled vocabulary (term) list, accurate spelling, abstracts conforming to the database publishers’ editorial guidelines, etc. The other type of quality was determined by the user; for example, was the information provided by the database timely, accurate, and in line with the scope of the database. Neither definition of quality was particularly good. I made this point in my lectures. Quality is like any abstract noun. Context defines it. Today quality means, as I was told after a lecture in Germany, “good enough.” I thought the serious young person was joking. He was not. This professional, who worked for an important European Union department, embraced “good enough” as the definition of quality.

The cited essay explains that there are two types of quality. The first is “purely functional.” I think that’s close to my definition of quality for old-fashioned databases. There were expensive to produce, difficult to index in a useful, systematic way even with our human plus smart software systems, and quite difficult to explain to a person unfamiliar with the difference between looking up something using Google and looking up a chemical structure in Chemical Abstracts. When I was working full time, I had a tough time explaining that Google was neither comprehensive nor focused on consistency. Google wanted to sell ads. Popularity determined quality, but that’s not what “quality” means to a person researching a case in a commercial database of legal information.

The second is “quality that fascinates.” I must admit that this is related to my notion of context, but I am not sure that “fascination” is exactly what I mean by context. A ball of string can fascinate the cat owner as well as the cat. Is this quality? Not in my book.

Several observations:

- Quality cannot be defined. I do believe that a company, its products, and an individual can produce objects or services that serve a purpose and do not anger the user. Well, maybe not anger. How about annoy, frustrate, stress, or force a product or service change. It is also my perception that quality is becoming a lost art like chipping stone arrowheads.

- The word “quality” can be defined in terms of cost cutting. I use products and services that are not without big flaws. Whether it is getting Microsoft Windows to print or preventing a Tesla from exploding into flames, short cuts seem to create issues. These folks are not angels in my opinion.

- The marketers, many of those whom I met were former journalists or art history majors, explain quality and other abstract terms in a way which obfuscates the verifiable behavior of a product or service. These folks are mendacious in my opinion.

Net net: Quality now means good enough.

That’s why nothing seems to work: Airport luggage handling, medical treatments of a president, electric vehicles, contacting a local government agency about a deer killed by a rolling smoke pickup truck driver, etc.

Quality products and services exist. Is it possible to find these using Bing, Google, or Yandex?

Nope.

Stephen E Arnold, August 25, 2022

A 2022 Real Time Classification Taxonomy

August 24, 2022

More than a decade ago, a semi clueless government entity in the European Union asked me to think about real time information flows. We looked around for technical papers, journal articles, and online information from investment banks and government agencies shooting stuff into space. (How about that real time communication from a satellite launched in 2009? Ho ho ho.)

I dug around in my paper files and found this early version of my research team’s approach to the subject of real time online information.

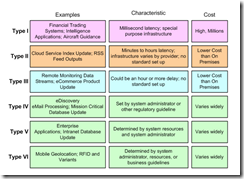

The team identified six principal types of real time information. I suppose today, these six categories are dinobaby eggs.

As evidence, I submit “Why You’re Probably Thinking About Real-Time Systems in the Wrong Way,” which illustrates how out-of-date our research has become. The article explains that there are three types of real time; to wit:

Hardware based real time systems, for example, high precision automated robotic assembly lines

Micro Batch real time systems; for example, ecommerce systems

Event driven real time systems; for example, embedded artificial intelligence systems

I am not sure how to fit our analysis into the three part categorization in the article.

What’s interesting is that the lack of understanding about real time, what’s needed to make them low latency, and affordable persists.

I will end with one question, “Do you think about real time in real time?”

Yes, ah, well, good for you!

Stephen E Arnold, August 24, 2022

The Metaverse? Not This Dinobaby

August 15, 2022

How many hours a day will this dinobaby spend in the metaverse? The answer, according to a blue chip consulting firm, is four hours a day. Now the source of this insight is McKinsey & Co., a firm somehow snared in the allegations related to generating revenue from a synthetic compound. I am not sure, but I think that the synthetic shares some similarity to heroin? Hey, why ot ask a family which has lost a son or daughter to the alleged opioid epidemic?

The McKinsey information appears in “People Expect to Spend at Least 4 Hours a Day in the Metaverse.” I learned:

Gen Z, millennials, and Gen X consumers expect to spend between four and five hours a day in the metaverse in the next five years. Comparatively, a recent Nielsen study found that consumers spend roughly five hours a day watching TV across various platforms.

If we assume that an old-fashioned work day is eight hours, that becomes about 1,000 hours a year of billable time plugged in or jacked in to the digital realm. I don’t know about you, but after watching students at a major university, I think the jack in time is on the low side. The mobile immersion was impressive.

The write up points out that an expert said:

“[Current AR smart glasses] give you a metaphor that looks like an Android phone on your face. So rectangles floating in space. That’s not enough for [mainstream smart glasses] adoption to happen,” Jared Ficklin, chief creative technologist at Argodesign, a former Magic Leap partner, said.

This dinobaby respectfully refuses to prep for digital addiction.

Stephen E Arnold, August 15, 2022

Pirate Library Illegally Preserves Terabytes of Text

August 15, 2022

Call it the Robin Hood of written material. (The legendary outlaw, not the brokerage outfit.) The Next Web tells us about an effort to preserve over seven terabytes of texts in, “The Pirate Library Mirror Wants to Preserve All Human Knowledge … Illegally.” Delighted writer Callum Booth explains:

“The Pirate Library Mirror is what it says on the tin: a mirror of existing libraries of pirated content. The project focuses specifically on books — although this may be expanded in the future. The project’s first goal is mirroring Z-Library, an illegal repository of journal articles, academic texts, and general-interest books. The site enforces a free download limit — 10 free books a day — and then charges users when they go above this. Z-Library originally branched off another site serving illegal books, Library Genesis. The former began its life by taking the latter site’s data, but making it easier to search. Since then, the people running Z-Library have built a collection that includes many books not available on its predecessor. This is important because, while Library Genesis is easily mirrorable, Z-Library is not — and that’s where the Pirate Library Mirror comes in. Those behind the new project cross-referenced Z-Library with Library Genesis, keeping what was only on the former, as that hasn’t been backed up. This amounts to over 7TB of books, articles, and journals.”

Instead of engaging in the labor-intensive process of transferring those newer Z-Library files to Genesis, those behind the Pirate Library simply bundle it all across multiple torrents. Because this is more about preservation than creating widespread access, the collection is not easily searchable and can only be reached via TOR. Still, it is illegal and could be shut down at any time. Booth acknowledges the complex tension between information access and the rights of content creators, but he is also downright giddy about the project. It reminds him of the “old school” internet, a wonderland of knowledge for the sake of knowledge. Ah, those were the days.

Cynthia Murrell, August 15, 2022

Wikipedia and Legal Decisions: What Do Paralegals Really Do for Information?

August 2, 2022

I read an interesting and, I think, important article about legal search and retrieval. The good news is that use of the go to resource is, so far, free. The bad news is that if one of the professional publishing outfits big wigs reads the cited article, an acquisition or special licensing deal may result. Hasta la vista, Wikipedia maybe?

Navigate to “How Wikipedia Influences Judicial Behavior.” The main idea of the article is that if a legal decision gets coverage in Wikipedia, that legal decision influences some future legal decisions. I interpret this as saying, “Lawyers want to reduce online legal research costs. Wikipedia is free. Therefore, junior lawyers and paralegals use free services like Wikipedia for their info-harvesting.

The write up states:

“To our knowledge, this is the first randomized field experiment that investigates the influence of legal sources on judicial behavior. And because randomized experiments are the gold standard for this type of research, we know the effect we are seeing is causation, not just correlation,” says MIT researcher Neil Thompson, the lead author of the research. “The fact that we wrote up all these cases, but the only ones that ended up on Wikipedia were those that won the proverbial “coin flip,” allows us to show that Wikipedia is influencing both what judges cite and how they write up their decisions. Our results also highlight an important public policy issue. With a source that is as widely used as Wikipedia, we want to make sure we are building institutions to ensure that the information is of the highest quality. The finding that judges or their staffs are using Wikipedia is a much bigger worry if the information they find there isn’t reliable.”

Now what happens if misinformation is injected into certain legal write ups available via Wikipedia?

The answer is, “Why that can’t happen.”

Of course not.

That’s exactly why this article providing some data and an interesting insight. Now is the study reproducible, in line with Stats 101, and produced in an objective manner? I have no idea.

Stephen E Arnold, August 2, 2022

Facebook, Twitter, Etc. May Have a Voting Issue

July 15, 2022

Former President Donald Trump claimed that any news not in his favor was “fake news.” While Trump’s claim is not true, large amounts of fake news has been swirling around the Internet since his administration and before. It is only getting worse, especially with conspiracy theorists that believe the 2020 election was fixed. Salon shares how the conspiracy theorists are chasing another fake villain: “‘Big Lie’ Vigilantes Publish Targets Online-But Facebook and Twitter Are Asleep At The Wheel.”

People who believe that the 2020 election was stolen from Trump have “ballot mules” between their crosshairs. Ballot mules are accused of dropping off absentee ballots during the previous election. Vigilantes have been encouraged to bring ballot mules to justice. They are using social media to “track them down.”

Facebook, Twitter, TikTok, and other social media platforms have policies that forbid violence, harassment, and impersonation of government officials. The vigilantes posted information about the purported ballot mules, but the pictures do not show them engaging in illegal activity. Luckily none of the “ballot mules” have been harmed.

“Disinformation researchers from the nonpartisan clean-government nonprofit Common Cause alerted Facebook and Twitter that the platforms were allowing users to post such incendiary claims in May. Not only did the claims lack evidence that crimes had been committed, but experts worry that poll workers, volunteers, and regular voters could face unwarranted harassment or physical harm if they are wrongfully accused of illegal election activity…

Emma Steiner, a disinformation analyst with Common Cause who sent warnings to the social-media companies, says the lack of action suggests that tech companies relaxed their efforts to police election-related threats ahead of the 2022 midterms. ‘This is the new playbook, and I’m worried that platforms are not prepared to deal with this tactic that encourages dangerous behavior,’ Steiner said.”

There is also a documentary Trump titled called 2000 Mules that claims ballot mules submitted thousands of false absentee ballots. Attorney General William Barr and other reputable people debunked the “documentary.” While the 2020 election was not rigged, conspiracy theorists creating and believing misinformation could damage the democratic process and the US’s future.

Whitney Grace, July 15, 2022

Apple: Intense Surveillance? The Core of the Ad Business

June 28, 2022

I read “US Senators Urge FTC to Investigate Apple for Transforming Online Advertising into an Intense System of Surveillance.” The write up reports:

Apple and Google “knowingly facilitated harmful practices by building advertising-specific tracking IDs into their mobile operating systems,” said the letter, which was signed by U.S. Senators Ron Wyden (D-Oregon), Elizabeth Warren (D-Massachusetts), and Cory Booker (D-New Jersey), as well as U.S. Representative Sara Jacobs (D-California).

There are references to Tracking IDs, “confusing phone settings, and monitoring a user when that user visits non-Apple sites and services. Mais oui! Surveillance yields data. Data allows ad targeting. Selling targeted ads generates money. Isn’t that what the game is about? Trillion dollar companies have to generate revenue to do good deeds, make TV shows, and make hundreds of thousands of devices obsolete with a single demo. Well, that’s my view.

Will something cause Apple to change?

Sure. TikTok maybe?

Stephen E Arnold, June 27, 21022

Work from Home Decorating Ideas

June 13, 2022

A happy quack to the person who alerted to me to this WFH (work from home) gallery of design ideas. The display of ingenuity is a reminder of the inner well springs of excellence within humans. The pristine settings would make Martha Stewart’s cell at FPC Alderson into a show stopper. The image only Web site presents more than 24 irl (in real life) decorating examples. Plan to share these with any teenagers or college students whom you know. Ask these individuals which approach is their fave. What fashionable touches will you incorporate into your Zoom nest?

Stephen E Arnold, June 13, 2022

Why Stuff Is Stupid: Yep, Online Is One Factor

May 16, 2022

I read “IQ Scores Are Falling and Have Been for Decades, New Study Finds.” Once again academic research has verified what anyone asking a young person to make change at a fast food restaurant knows: Ain’t happening.

The article reports:

IQ scores have been steadily falling for the past few decades, and environmental factors are to blame, a new study says. The research suggests that genes aren’t what’s driving the decline in IQ scores…

What, pray tell and back up with allegedly accurate data from numerous sources? I learned:

“The causes in IQ increases over time and now the decline is due to environmental factors,” said Rogeburg [Ole Rogeberg, a senior research fellow at the Ragnar Frisch Center for Economic Research in Norway], who believes the change is not due to genetics. “It’s not that dumb people are having more kids than smart people, to put it crudely. It’s something to do with the environment, because we’re seeing the same differences within families,” he said. These environmental factors could include changes in the education system and media environment, nutrition, reading less and being online more, Rogeberg said.

Ah, ha. Media and online.

Were not these innovations going to super charge learning?

I know how it is working out when I watch a teen struggling to calculate that 57 cents from $1.00 is $5.00 and 43 cents. Yes!

I am not sure to what to make of another research study. “Why Do Those with Higher IQs Live Longer? A New Study Points to Answers” reveals:

“The slight benefit to longevity from higher intelligence seems to increase all the way up the intelligence scale, so that very smart people live longer than smart people, who live longer than averagely intelligent people, and so on.” The researchers … found an association between childhood intelligence and a reduced risk of death from dementia and, on a smaller scale, suicide. Similar results were seen among men and women, except for lower rates of suicide, which had a correlation to higher childhood intelligence among men but not women.

My rule of thumb is not to stand in front of a smart self-driving automobile.

Stephen E Arnold, May 16, 2022

Screen Addiction: Digital Gratification Anytime, Anyplace

May 11, 2022

We are addicted to screens. The screens can be any size so long as they contain instantaneous gratification content. Our screen addiction has altered our brain chemistry and Medium explains how in the article, “Your Brain-Altering Screen Addiction Explained. With Ancient Memes.” The article opens by telling readers to learn how much time they spend on their phones by looking at their usage data. It is quickly followed by a line that puts into perspective how much time people spend on their phones related to waking hours.

The shocking fact is that Americans spend four hours on mobile devices and that is not including TV and desktop time! The Center for Humane Technology created the Ledge of Harms, an evidenced-based list of harms resulting from digital addiction, mostly social media. The ledger explains too much screen time causes cognitive impairment and that means:

“The level of social media use on a given day is linked to a significant correlated increase in memory failure the next day.

• The mere presence of your smartphone, even when it’s turned off and face down, drains your attention.

• 3 months after starting to use a smartphone, users experience a significant decrease in mental arithmetic scores (indicating reduced attentional capacity) and a significant increase in social conformity.

• Most Americans spend 1 hour per day just dealing with distractions and trying to get back on track — that’s 5 wasted full weeks a year!

• Several dozen research studies indicate that higher levels of switching between different media channels are significantly linked to lower levels of both working memory and long-term memory.

• Studies even showed that people who opened Facebook frequently and stayed on Facebook longer tended to have reduced gray matter volume in the brain. “

Screen addiction causes harm in the same way as drugs and alcohol. The same thing we turn to reduce depression, anxiety, and isolation creates more of it. Another grueling statistic is that we spend an average of nineteen seconds on content before we switch to another. The switch creates a high by the release of endorphins, so we end up being manipulated by attention-extractive economics.

Tech companies want to exploit this positive feedback loop. Our attention spans are inversely proportional to the better their technology and algorithms are. The positive feedback loop is compounded by us spending more time at home, instead of participating in the real world.

How does one get the digital monkey off one’s back? Cold turkey, gentle reader. Much better than an opioid.

Whitney Grace, May 11, 2022