Surprise! Smart Software and Medical Outputs May Kill You

February 29, 2024

This essay is the work of a dumb humanoid. No smart software required.

This essay is the work of a dumb humanoid. No smart software required.

Have you been inhaling AI hype today? Exhale slowly, then read “Generating Medical Errors: GenAI and Erroneous Medical References,” produced by the esteemed university with a reputation for shaking the AI cucarachas and singing loudly “Ai, Ai, Yi.” The write up is an output of the non-plagiarizing professionals in the Human Centered Artificial Intelligence unit.

The researchers report states:

…Large language models used widely for medical assessments cannot back up claims.

Here’s what the HAI blog post states:

we develop an approach to verify how well LLMs are able to cite medical references and whether these references actually support the claims generated by the models. The short answer: poorly. For the most advanced model (GPT-4 with retrieval augmented generation), 30% of individual statements are unsupported and nearly half of its responses are not fully supported.

Okay, poorly. The disconnect is that the output sounds good, but the information is distorted, off base, or possibly inappropriate.

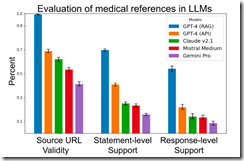

What I found interesting is a stack ranking of widely used AI “systems.” Here’s the chart from the HAI article:

The least “poor” are the Sam AI-Man systems. In the middle is the Anthropic outfit. Bringing up the rear is the French “small” LLM Mistral system. And guess which system is dead last in this Stanford report?

Give up?

The Google. And not just the Google. The laggard is the Gemini system which was Bard, a smart software which rolled out after the Softies caught the Google by surprise about 14 months ago. Last in URL validity, last in statement level support, and last in response level support.

The good news is that most research studies are non reproducible or, like the former president of Stanford’s work, fabricated. As a result, I think these assertions will be easy for an art history major working in Google’s PR confection machine will bat them away like annoying flies in Canberra, Australia.

But last from researchers at the estimable institution where Google, Snorkel and other wonderful services were invented? That’s a surprise like the medical information which might have unexpected consequences for Aunt Mille or Uncle Fred.

Stephen E Arnold, February 29, 2024

It Is Here: The AI Generation

February 2, 2024

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

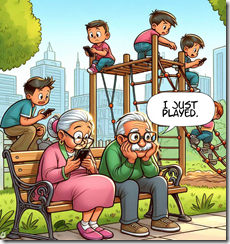

Yes, another digital generation has arrived. The last two or three have been stunning, particularly when compared to my childhood in central Illinois. We played hide and seek; now the youthful create fake Taylor Swift videos. Ah, progress.

I read “Qustodio Releases 5th Annual Report Studying Children’s Digital Habits, Born Connected: The Rise of the AI Generation.” I have zero clue if the data are actual factual. With the recent information about factual creativity at the Harvard medical brain trust, nothing will surprise me. Nevertheless, let me highlight several factoids and then, of course, offer some unwanted Beyond Search comments. Hey, it is a free blog, and I have some friskiness in my dinobaby step.

Memories. Thanks, MSFT Copilot Bing thing. Not even close to what I specified.

The sample involved “400,000 families and schools.” I don’t remember too much about my Statistics 101 course 60 years ago, but the sample size seems — interesting. Here’s what Qustodio found:

YouTube is number one for streaming, kiddies spent 60 percent more time on TikTok

How much time goes to couch potato-ing? Here’s the answer:

TikTok continued to captivate with children spending a global average of 112 minutes daily on the app – up from 107 in 2022. UK kids were particularly fond of the bottomless scroll as they racked up 127 mins/day.

Why read, play outdoors, or fiddle with a chemistry set? Just kick back and check out ASMR, being thin, and dance move videos. Sounds tasty, doesn’t it?

And what is the most popular kiddie app? Here’s the answer:

Snapchat.

If you want to buy the full report, click this link.

Several observations:

- The smart software angle may be in the full report, but the summary skirts the issue, recycling the same grim numbers: More video, less of other activities like being a child

- Will this “generation” of people be able to differentiate reality from fake anything? My hunch is that the belief that these young folks have super tuned baloney radar may be — baloney.

- A sample of 400,000? Yeah.

Net net: I am glad to be an old dinobaby. Really, really happy.

Stephen E Arnold, February 2, 2024

Robots, Hard and Soft, Moving Slowly. Very Slooowly. Not to Worry, Humanoids

February 1, 2024

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

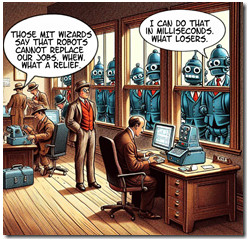

CNN that bastion of “real” journalism published a surprising story: “We May Not Lose Our Jobs to Robots So Quickly, MIT Study Finds.” Wait, isn’t MIT the outfit which had a tie up with the interesting Jeffrey Epstein? Oh, well.

The robots have learned that they can do humanoid jobs quickly and easily. But the robots are stupid, right? Yes, they are, but the managers looking for cost reductions and workforce reductions are not. Thanks, MSFT Copilot Bing thing. How the security of the MSFT email today?

The story presents as actual factual an MIT-linked study which seems to go against the general drift of smart software, smart machines, and smart investors. The story reports:

new research suggests that the economy isn’t ready for machines to put most humans out of work.

The fresh research finds that the impact of AI on the labor market will likely have a much slower adoption than some had previously feared as the AI revolution continues to dominate headlines. This carries hopeful implications for policymakers currently looking at ways to offset the worst of the labor market impacts linked to the recent rise of AI.

The story adds:

One key finding, for example, is that only about 23% of the wages paid to humans right now for jobs that could potentially be done by AI tools would be cost-effective for employers to replace with machines right now. While this could change over time, the overall findings suggest that job disruption from AI will likely unfurl at a gradual pace.

The intriguing facet of the report and the research itself is that it seems to suggest that the present approach to smart stuff is working just fine, thank you very much. Why speed up or slow down? The “unfurling” is a slow process. No need for these professionals to panic as major firms push forward with a range of hard and soft robots:

- Consulting firms. Has MIT checked out Deloitte’s posture toward smart software and soft robots?

- Law firms. Has MIT talked to any of the Top 20 law firms about their use of smart software?

- Academic researchers. Has MIT talked to any of the graduate students or undergraduates about their use of smart software or soft robots to generate bibliographies, summaries of possibly non-reproducible studies, or books mentioning their professor?

- Policeware vendors. Companies like Babel Street and Recorded Future are putting pedal to the metal with regard to smart software.

My hunch is that MIT is not paying attention to the happy robots at Tesla or the bad actors using software robots to poke through the cyber defenses of numerous outfits.

Does CNN ask questions? Not that I noticed. Plus, MIT appears to want good news PR. I would too if I were known to be pals with certain interesting individuals.

Stephen E Arnold, February 1, 2024

AI and Web Search: A Meh-crosoft and Google Mismatch

January 25, 2024

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

I read a shocking report summary. Is the report like one of those Harvard Medical scholarly articles or an essay from the former president of Stanford University? I don’t know. Nevertheless, let’s look at the assertions in “Report: ChatGPT Hasn’t Helped Bing Compete With Google.” I am not sure if the information provides convincing proof that Googzilla is a big, healthy market dominator or if Microsoft has been fooling itself about the power of the artificial intelligence revolution.

The young inventor presents his next big thing to a savvy senior executive at a techno-feudal company. The senior executive is impressed. Are you? I know I am. Thanks, MSFT Copilot Bing thing. Too bad you timed out and told me, “I apologize for the confusion. I’ll try to create a more cartoon-style illustration this time.” Then you crashed. Good enough, right?

Let’s look at the write up. I noted this passage which is coming to me third, maybe fourth hand, but I am a dinobaby and I go with the online flow:

Microsoft added the generative artificial intelligence (AI) tool to its search engine early last year after investing $10 billion in ChatGPT creator OpenAI. But according to a recent Bloomberg News report — which cited data analytics company StatCounter — Bing ended 2023 with just 3.4% of the worldwide search market, compared to Google’s 91.6% share. That’s up less than 1 percentage point since the company announced the ChatGPT integration last January.

I am okay with the $10 billion. Why not bet big? The tactics works for some each year at the Kentucky Derby. I don’t know about the 91.6 number, however. The point six is troubling. What’s with precision when dealing with a result that makes clear that of 100 random people on line at the ever efficient BWI Airport, only eight will know how to retrieve information from another Web search system; for example, the busy Bing or the super reliable Yandex.ru service.

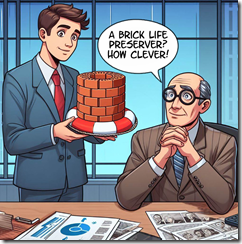

If we assume that the Bing information of modest user uptake, those $10 billion were not enough to do much more than get the management experts at Alphabet to press the Red Alert fire alarm. One could reason: Google is a monopoly in spirit if not in actual fact. If we accept the market share of Bing, Microsoft is putting life preservers manufactured with marketing foam and bricks on its Paul Allen-esque super yacht.

The write up says via what looks like recycled information:

“We are at the gold rush moment when it comes to AI and search,” Shane Greenstein, an economist and professor at Harvard Business School, told Bloomberg. “At the moment, I doubt AI will move the needle because, in search, you need a flywheel: the more searches you have, the better answers are. Google is the only firm who has this dynamic well-established.”

Yeah, Harvard. Oh, well, the sweatshirts are recognized the world over. Accuracy, trust, and integrity implied too.

Net net: What’s next? Will Microsoft make it even more difficult to use another outfit’s search system. Swisscows.com, you may be headed for the abattoir. StartPage.com, you will face your end.

Stephen E Arnold, January 25, 2024

The Click Derbies: Strong Runners Take the Lead

December 12, 2023

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

Two unrelated reports about user behavior strike me as important.

The first is data from Pew Research about teens and social media. Are the data “new”? The phrase about “almost constant” usage is like the decision regarding Google as a monopoly. Obvious behavior is difficult to overlook.

“Teens, Social Media and Technology” reports some allegedly accurate data I find suggestive; for example:

- 90 percent of teenagers use YouTube. There are no data about what the teens watch; for example transparent clothing, how to be healthy, or videos about 19th century philosophers

- TikTok reaches 70 percent of teens in the 15 to 17 year old demographic. These are tomorrow’s leaders in business, technology, and medical research who will have fine tuned their attention spans to the world of short, jazzy video

- Facebook’s share of teens is now in the 30 percent range and the “improved” Twitter are apparently losing some of their magnetic appeal.

The surprising factoids concern the 20 percent of the teens in the sample who use TikTok and YouTube “almost constantly.” The share of teens who say they are online with social media almost constantly has almost doubled in the last seven years. How much time remains to do homework? That question is not answered, but test scores suggest, “Not too much” for some teens.

A young and sprightly Temu is making the older runners look like losers. Thanks, MSFT Copilot. Good enough again.

The research report states:

Larger shares of Black and Hispanic teens report being on YouTube, Instagram and TikTok almost constantly, compared with a smaller share of White teens who say the same. Hispanic teens stand out in TikTok and Snapchat use. For instance, 32% of Hispanic teens say they are on TikTok almost constantly, compared with 20% of Black teens and 10% of White teens.

Social media and social media access are essentially unregulated by parents, educational institutions, and the government. Allowing teens to immerse themselves in streams of digital content may have some short term and long term downsides. Perhaps it is too late to reverse the corrosive effects of these information streams? I don’t want to be a Negative Ned, so I will say, “Of course not.”

The second report is about Temu, which allegedly has some connections to the Middle Kingdom. “Shoppers Spend Almost Twice as Long on Temu App Than Key Rivals” contains data which may or may not be spot on. Nevertheless, let’s look at what the article reports from an outfit called Apptopia:

On average, users spent 18 minutes per day on the Temu app in the second quarter, compared with 10 minutes for Amazon and 11 minutes for Alibaba Group Holding Ltd.’s AliExpress, based on Apptopia’s device-level analysis. Among younger users, the time spent on Temu was 19 minutes, it said.

Let’s assume that the data characterize one behavior: Those in the sample spend more time on the Temu app than on the Amazon service. I want to point out that comparing app usage to the undefined “Amazon” is an issue. Nevertheless, one question pops up: “Amazon, what’s causing users to spend less time on your service?” Maybe Amazon has a better interface so a person can find a product more quickly. Maybe Amazon’s crazy quilt of prices turn people off? Maybe the magical “price changes” cause individuals like me to report that bait-and-witch methods are possibly in use? Maybe people see an Amazon price for something manufactured somewhere far from Toledo, and think, “I will look elsewhere, get a better price, and ignore Toledo (a charming city).

The article points to a different reason; to wit:

The addictive app is core to the strategy. It allows users to play games to win rewards, including spinning a roulette-like wheel to win a coupon — which goes up in value if you buy something within 10 minutes. The Temu app is available in more than 40 countries, though none have taken to it like customers in the US, where it’s Apple Inc.’s top app most days this year and sales have well and truly surpassed bargain-shopping giant Shein.

I interpret this to mean: Amazon is behind the times, overly bureaucratic, reacting to AI by trying to support every AI solution, and worrying about its regulator friends in Washington and Brussels.

Net net: On one hand we have an ideal conduit to deliver weaponized information to young people. On the other, we have once-nimble US companies watching Temu score goals.

Stephen E Arnold, December 12, 2023

Gallup on Social Media: Just One, Tiny, Irrelevant Data Point Missing

October 23, 2023

![Vea4_thumb_thumb_thumb_thumb_thumb_t[2] Vea4_thumb_thumb_thumb_thumb_thumb_t[2]](https://arnoldit.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Vea4_thumb_thumb_thumb_thumb_thumb_t2_thumb-25.gif) Note: This essay is the work of a real and still-alive dinobaby. No smart software involved, just a dumb humanoid.

Note: This essay is the work of a real and still-alive dinobaby. No smart software involved, just a dumb humanoid.

I read “Teens Spend Average of 4.8 Hours on Social Media Per Day.” I like these insights into how intelligence is being whittled away.

Me? A dumb bunny. Thanks, MidJourney. What dumb bunny inspired you?

Three findings caught may attention and one, tiny, irrelevant data point I noticed was missing. Let’s look at three of the hooks snagging me.

First, the write up reveals:

Across age groups, the average time spent on social media ranges from as low as 4.1 hours per day for 13-year-olds to as high as 5.8 hours per day for 17-year-olds.

Doesn’t that seem like a large chunk of one’s day?

Second, I learned that the research unearthed this insight:

Teens report spending an average of 1.9 hours per day on YouTube and 1.5 hours per day on TikTok

I assume the bright spot is that only two plus hours are invested in reading X.com, Instagram, and encrypted messages.

Third, I learned:

The least conscientious adolescents — those scoring in the bottom quartile on the four items in the survey — spend an average of 1.2 hours more on social media per day than those who are highly conscientious (in the top quartile of the scale). Of the remaining Big 5 personality traits, emotional stability, openness to experience, agreeableness and extroversion are all negatively correlated with social media use, but the associations are weaker compared with conscientiousness.

Does this mean that social media is particularly effective on the most vulnerable youth?

Now let me point out the one item of data I noted was missing:

How much time does this sample spend reading?

I think I know the answer.

Stephen E Arnold, October 23, 2023

Recent Facebook Experiments Rely on Proprietary Meta Data

September 25, 2023

When one has proprietary data, researchers who want to study that data must work with you. That gives Meta the home court advantage in a series of recent studies, we learn from the Science‘s article, “Does Social Media Polarize Voters? Unprecedented Experiments on Facebook Users Reveal Surprises.” The 2020 Facebook and Instagram Election Study has produced four papers so far with 12 more on the way. The large-scale experiments confirm Facebook’s algorithm pushes misinformation and reinforces filter bubbles, especially on the right. However, they seem to indicate less influence on users’ views and behavior than many expected. Hmm, why might that be? Writer Kai Kupferschmidt states:

“But the way the research was done, in partnership with Meta, is getting as much scrutiny as the results themselves. Meta collaborated with 17 outside scientists who were not paid by the company, were free to decide what analyses to run, and were given final say over the content of the research papers. But to protect the privacy of Facebook and Instagram users, the outside researchers were not allowed to handle the raw data. This is not how research on the potential dangers of social media should be conducted, says Joe Bak-Coleman, a social scientist at the Columbia School of Journalism.”

We agree, but when companies maintain a stranglehold on data researchers’ hands are tied. Is it any wonder big tech balks at calls for transparency? The article also notes:

“Scientists studying social media may have to rely more on collaborations with companies like Meta in the future, says [participating researcher Deen] Freelon. Both Twitter and Reddit recently restricted researchers’ access to their application programming interfaces or APIs, he notes, which researchers could previously use to gather data. Similar collaborations have become more common in economics, political science, and other fields, says [participating researcher Brendan] Nyhan. ‘One of the most important frontiers of social science research is access to proprietary data of various sorts, which requires negotiating these one-off collaboration agreements,’ he says. That means dependence on someone to provide access and engage in good faith, and raises concerns about companies’ motivations, he acknowledges.”

See the article for more details on the experiments, their results so far, and their limitations. Social scientist Michael Wagner, who observed the study and wrote a commentary to accompany their publication, sees the project as a net good. However, he acknowledges, future research should not be based on this model where the company being studied holds all the data cards. But what is the alternative?

Cynthia Murrell, September 25, 2023

Useful Probability Wording from the UK Ministry of Defence

August 8, 2023

Note: This essay is the work of a real and still-alive dinobaby. No smart software involved, just a dumb humanoid.

Note: This essay is the work of a real and still-alive dinobaby. No smart software involved, just a dumb humanoid.

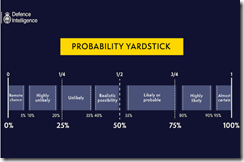

“Have You Ever Wondered Why Defence Intelligence Uses Terms Like “Unlikely” or “Realistic Possibility” When We Assess Russia’s War in Ukraine?” provides two useful items of information. Many people will be familiar with the idea of a “probability yardstick.” Others — like some podcast pundits and YouTube yodas — may not have a firm grasp on the words and their meaning.

I have reproduced the Ministry of Defence’s Probability Yardstick, which appeared in February 2023 in the unclassified posting:

Some investment analysts and business consultants have adopted this or a similar “yardstick.” Many organizations have this type of visual representation of event likelihoods.

The article does not provide real-life examples of the use of the yardstick. That’s is a good decision. For those engaged in analysis and data crunching, the idea of converting “numbers” into a point on a yardstick facilitates the communication of risk.

Here’s one recent example. A question like the impact of streaming on US cable companies is presented in the article “As Cable TV is Losing Millions of Subscribers, YouTube TV Is Now The 5th Largest TV Provider & Could Soon Be The 4th Largest” does not communicate the type of information a senior executive wants; that is, how likely is it the trend will continue. Pegging the loss of subscribers on the yardstick in either the “likely or probable” or “highly likely” communicates quickly and without word salad. The “explanation” can, of course, be provided.

In fast-moving situations, the terminology of the probability yardstick and its presentation of what is a type of confidence score is often useful. By the way, in the cited Cable TV article, the future is sunny for Google and TikTok, but not so good for the traditional companies.

Stephen E Arnold, August 8, 2023

Research 2023: Is There a Methodology of Control via Mendacious Analysis

August 8, 2023

Note: This essay is the work of a real and still-alive dinobaby. No smart software involved, just a dumb humanoid.

Note: This essay is the work of a real and still-alive dinobaby. No smart software involved, just a dumb humanoid.

I read “How Facebook Does (and Doesn’t) Shape Our Political Views.” I am not sure what to conclude from the analysis of four studies about Facebook (is it Zuckbook?) presumably completed with some cooperation from the social media giant itself. The message I carried away from the write up is that tainted research may be the principal result of these supervised studies.

The up and coming leader says to a research assistant, “I am telling you. Manipulate or make up the data. I want the results I wrote about supported by your analysis. If you don’t do what I say, there will be consequences.” MidJourney does know how to make a totally fake leader appear intense.

Consider the state of research in 2023. I have mentioned the problem with Stanford University’s president and his making up data. I want to link the Stanford president’s approach to research with Facebook (Meta). The university has had some effect on companies in the Silicon Valley region. And Facebook (Meta) employs a number of Stanford graduates. For me, then, it is logical to consider the approach of the university to objective research and the behavior of a company with some Stanford DNA to share certain characteristics.

“How Facebook Does (and Doesn’t) Shape Our Political Views” offers this observation based on “research”:

“… the findings are consistent with the idea that Facebook represents only one facet of the broader media ecosystem…”

The summary of the Facebook-chaperoned research cites an expert who correctly in my my identifies two challenges presented by the “research”:

- Researchers don’t know what questions to ask. I think this is part of the “don’t know what they don’t know.” I accept this idea because I have witnessed it. (Example: A reporter asking me about sources of third party data used to spy on Americans. I ignored the request for information and disconnected from the reporter’s call.)

- The research was done on Facebook’s “terms”. Yes, powerful people need control; otherwise, the risk of losing power is created. In this case, Facebook (Meta) wants to deflect criticism and try to make clear that the company’s hand was not on the control panel.

Are there parallels between what the fabricating president of Stanford did with data and what Facebook (Meta) has done with its research initiative? Shaping the truth is common to both examples.

In Stanford’s Ideal Destiny, William James said this about about Stanford:

It is the quality of its men that makes the quality of a university.

What links the actions of Stanford’s soon-to-be-former president and Facebook (Meta)? My answer would be, “Creating a false version of objective data is the name of the game.” Professor James, I surmise, would not be impressed.

Stephen E Arnold, August 8, 2023

Research: A Suspicious Activity and Deserving of a Big Blinking X?

August 2, 2023

Note: This essay is the work of a real and still-alive dinobaby. No smart software involved, just a dumb humanoid.

Note: This essay is the work of a real and still-alive dinobaby. No smart software involved, just a dumb humanoid.

The Stanford president does it. The Harvard ethics professor does it. Many journal paper authors do it. Why can’t those probing the innards of the company formerly known as Twatter do it?

I suppose those researchers can. The response to research one doesn’t accept can be a simple, “The data processes require review.” But no, no, no. The response elicited from the Twatter is presented in “X Sues Hate Speech Researchers Whose Scare Campaign Spooked Twitter Advertisers.” The headline is loaded with delicious weaponized words in my opinion; for instance, the ever popular “hate speech”, the phrase “scare campaign,” and “spooked.”

MidJourney, after some coaxing, spit out a frightened audience of past, present, and potential Twatter advertisers. I am not sure the smart software captured the reality of an advertiser faced with some brand-injuring information.

Wording aside, the totally objective real news write up reports:

X Corp sued a nonprofit, the Center for Countering Digital Hate (CCDH), for allegedly “actively working to assert false and misleading claims” regarding spiking levels of hate speech on X and successfully “encouraging advertisers to pause investment on the platform,” Twitter’s blog said.

I found this statement interesting:

X is alleging that CCDH is being secretly funded by foreign governments and X competitors to lob this attack on the platform, as well as claiming that CCDH is actively working to censor opposing viewpoints on the platform. Here, X is echoing statements of US Senator Josh Hawley (R-Mo.), who accused the CCDH of being a “foreign dark money group” in 2021—following a CCDH report on 12 social media accounts responsible for 65 percent of COVID-19 vaccine misinformation, Fox Business reported.

Imagine. The Musker questioning research.

Exactly what is “accurate” today? One could query the Stanford president, the Harvard ethicist, Mr. Musk, or the executives of the Center for Countering Digital Hate. Wow. That sounds like work, probably as daunting as reviewing the methodology used for the report.

My moral and ethical compass is squarely tracking lunch today. No attorneys invited. No litigation necessary if my soup is cold. I will be dining in a location far from the spot once dominated by a quite beefy, blinking letter signifying Twatter. You know. I think I misspelled “tweeter.” I will fix it soon. Sorry.

Stephen E Arnold, August 2, 2023