Microsoft Investigates Itself and a Customer: Finding? Nothing to See Here

May 26, 2025

No AI, just a dinobaby and his itty bitty computer.

No AI, just a dinobaby and his itty bitty computer.

GeekWire, creator of the occasional podcast, published “Microsoft: No Evidence Israeli Military Used Technology to Harm Civilians, Reviews Find.” When an outfit emits occasional podcasts published a story, I know that the information is 100 percent accurate. GeekWire has written about Microsoft and its outstanding software. Like Windows Central, the enthusiasm for what the Softies do is a key feature of the information.

What did I learn included:

- Israel’s military uses Microsoft technology

- Israel may have used Microsoft technology to harm non-civilians

- The study was conducted by the detail-oriented and consistently objective company. Self-study is known to be reliable, a bit like research papers from Harvard which are a bit dicey in the reproducible results department

- The data available for the self-study was limited; that is, Microsoft relied on an incomplete data set because certain information was presumably classified

- Microsoft “provided limited emergency support to the Israeli government following the October 7, 2023, Hamas attacks.”

Yeah, that sounds rock solid to me.

Why did the creator of Bob and Clippy sit down and study its navel? The write up reported:

Microsoft said it launched the reviews in response to concerns from employees and the public over media reports alleging that its Azure cloud platform and AI technologies were being used by the Israeli military to harm civilians.

The Microsoft investigation concluded:

its recent reviews found no evidence that the Israeli Ministry of Defense has failed to comply with its terms of service or AI Code of Conduct.

That’s a fact. More than rock solid, the fact is like one of those pre-Inca megaliths. That’s really solid.

GeekWire goes out on a limb in my opinion when it includes in the write up a statement from an individual who does not see eye to eye with the Softies’ investigation. Here’s that passage:

A former Microsoft employee who was fired after protesting the company’s ties to the Israeli military, he said the company’s statement is “filled with both lies and contradictions.”

What’s with the allegation of “lies and contradictions”? Get with the facts. Skip the bogus alternative facts.

I do recall that several years ago I was told by an Israeli intelware company that their service was built on Microsoft technology. Now here’s the key point. I asked if the cloud system worked on Amazon? The response was total confusion. In that English language meeting, I wondered if I had suffered a neural malfunction and posed the question, “Votre système fonctionne-t-il sur le service cloud d’Amazon?” in French, not English.

The idea that this firm’s state-of-the-art intelware would be anything other than Microsoft centric was a total surprise to those in the meeting. It seemed to me that this company’s intelware like others developed in Israel would be non Microsoft was inconceivable.

Obviously these professionals were not aware that intelware systems (some of which failed to detect threats prior to the October 2023 attack) would be modified so that only adversary military personnel would be harmed. That’s what the Microsoft investigation just proved.

Based on my experience, Israel’s military innovations are robust despite that October 2023 misstep. Furthermore, warfighting systems if they do run on Microsoft software and systems have the ability to discriminate between combatants and non-combatants. This is an important technical capability and almost on a par with the Bob interface, Clippy, and AI in Notepad.

I don’t know about you, but the Microsoft investigation put my mind at ease.

Stephen E Arnold, May 26, 2025

US Cloud Dominance? China Finds a Gap and Cuts a Path to the Middle East

May 11, 2025

No AI, just the dinobaby expressing his opinions to Zellenials.

No AI, just the dinobaby expressing his opinions to Zellenials.

‘How China Is Gaining Ground in the Middle East Cloud Computing Race” provides a summary of what may be a destabilizing move in the cloud computing market. The article says:

Huawei and Alibaba are outpacing established U.S. providers by aligning with government priorities and addressing data sovereignty concerns.

The “U.S. providers” are Amazon, Google, Microsoft, Oracle. The Chinese companies making gains in the Middle East include Alibaba, Huawei, and TenCent. Others are likely to follow.

The article notes:

Alibaba Cloud expanded strategically by opening data centers in the UAE in 2022 and Saudi Arabia last year. It entered the Saudi market by setting up a venture with STC. The Saudi Cloud Computing Company will support the kingdom’s Vision 2030 goals, under which the government hopes to diversify the economy away from oil dependency.

What’s China’s marketing angle? The write up identifies alignment and more sensitivity to “data sovereignty” in key Middle Eastern countries. But the secret sauce is, according the the write up:

A key differentiator has been the Chinese providers’ approach to artificial intelligence. While U.S. companies have been slow to adopt AI solutions in the region, Chinese providers have aggressively embedded AI into their offerings at a time when Gulf nations are pursuing AI leadership. During the Huawei Global AI Summit last year, Huawei Cloud’s chief technology officer, Bruno Zhang, showed how its AI could cut Saudi hospital diagnostic times by 40% using localized Arabic language models — a tangible benefit that theoretical AI platforms from Western providers couldn’t match.

This statement may or may not be 100 percent correct. For this blog post, let’s assume that it is close enough for horse shoes. First, the US cloud providers are positioned as “slow”. What happened to the go fast angle. Wasn’t Microsoft a “leader” in AI, catching Google napping in its cubicle? Google declared some sort of an emergency and the AI carnival put up its midway.

Second, the Gulf “nations” wanted AI leadership, so Huawei presented a “tangible benefit” in the form of a diagnostic time reduction and localized Arabic language models. I know that US cloud providers provide translation services, but the pointy end of the stick shoved into the couch potato US cloud services was “localized language models.”

Furthermore, the Chinese providers provide cloud services and support on premises plus cloud functions. The “hybrid” angle matches the needs of some Middle Eastern information systems professionals’ ideas. The write up says:

The hybrid approach plays directly to the strengths of Chinese providers, who recognized this market preference early and built their regional strategy around it.

The Chinese vendors provide an approach that matches what prospects want. Seems simple and obvious. However, the article includes a quote that hints at another positive for the Chinese cloud players; to wit:

“The Chinese companies are showing that success in the Middle East depends as much on trust and cooperation as it does on computing power,” Luis Bravo, senior research analyst at Texas-based data center Hawk…

For me the differentiator may not be price, hybrid willingness, or localization. The killer word is trust. If the Gulf States do not trust the US vendors, China is likely to displace yesterday’s “only game in town” crowd.

Yep, trust. A killer benefit in some deals.

Stephen E Arnold, May 11, 2025

Azure Insights: A Useful and Amusing Resource

March 4, 2025

This blog post is the work of a real live dinobaby. At age 80, I will be heading to the big natural history museum in the sky. Until then, creative people surprise and delight me.

This blog post is the work of a real live dinobaby. At age 80, I will be heading to the big natural history museum in the sky. Until then, creative people surprise and delight me.

I read some of the posts in a service named “Daily Azure Sh$t.” You can find the content on Mastodon.social at this link. Reading through the litany of issues, glitches, and goofs had me in stitches. If you work with Microsoft Azure, you might not be reading the Mastodon stomps with a chortle. You might be a little worried.

The post states:

This account is obviously not affiliated with Microsoft.

My hunch is that like other Microsoft-skeptical blogs, some of the Softies’ legal eagles will take flight. Upon determining the individual responsible for the humorous summary of technical antics, the individual may find that knocking off the service is one of the better ideas a professional might have. But until then, check out the newsy items.

As interesting are the comments on Hacker News. You will find these at this link.

For your delectation and elucidation, here are some of the comments from Hacker News:

- Osigurdson said: “Businesses are theoretically all about money but end up being driven by pride half the time.”

- Amarant said: “Azure was just utterly unable to deliver on anything they promised, thus the write-off on my part.”

- Abrookewood said: “Years ago, we migrated of Rackspace to Azure, but the database latency was diabolical. In the end, we got better performance by pointing the Azure web servers to the old database that was still in Rackspace than we did trying to use the database that was supposedly in the same data center.”

You may have a sense of humor different from mine. Enjoy either the laughing or the weeping.

Stephen E Arnold, March 9, 2025

The EU Rains on the US Cloud Parade

March 3, 2025

At least one European has caught on. Dutch blogger Bert Hubert is sounding the alarm to his fellow Europeans in the post, "It Is No Longer Safe to Move Our Governments and Societies to US Clouds." Governments and organizations across Europe have been transitioning systems to American cloud providers for reasons of cost and ease of use. Hubert implores them to prioritize security instead. He writes:

"We now have the bizarre situation that anyone with any sense can see that America is no longer a reliable partner, and that the entire large-scale US business world bows to Trump’s dictatorial will, but we STILL are doing everything we can to transfer entire governments and most of our own businesses to their clouds. Not only is it scary to have all your data available to US spying, it is also a huge risk for your business/government continuity. From now on, all our business processes can be brought to a halt with the push of a button in the US. And not only will everything then stop, will we ever get our data back? Or are we being held hostage? This is not a theoretical scenario, something like this has already happened."

US firms have been wildly successful in building reliance on their products around the world. So much so, we are told, that some officials would rather deny reality than switch to alternative systems. The post states:

"’Negotiating with reality’ is for example the letter three Dutch government ministers sent last week. Is it wise to report every applicant to your secret service directly to Google, just to get some statistics? The answer the government sent: even if we do that, we don’t, because ‘Google cannot see the IP address‘. This is complete nonsense of course, but it’s the kind of thing you tell yourself (or let others tell you) when you don’t want to face reality (or can’t)."

Though Hubert does not especially like Microsoft tools, for example, he admits Europeans are accustomed to them and have "become quite good at using them." But that is not enough reason to leave data vulnerable to "King Trump," he writes. Other options exist, even if they may require a bit of effort to implement. Security or convenience: pick one.

Cynthia Murrell, March 3, 2025

Are These Googlers Flailing? (Yes, the Word Has “AI” in It Too)

February 12, 2025

Is the Byte write up on the money? I don’t know, but I enjoyed it. Navigate to “Google’s Finances Are in Chaos As the Company Flails at Unpopular AI. Is the Momentum of AI Starting to Wane?” I am not sure that AI is in its waning moment. Deepseek has ignited a fire under some outfits. But I am not going to critic the write up. I want to highlight some of its interesting information. Let’s go, as Anatoly the gym Meister says, just with an Eastern European accent.

Here’s the first statement in the article which caught my attention:

Google’s parent company Alphabet failed to hit sales targets, falling a 0.1 percent short of Wall Street’s revenue expectations — a fraction of a point that’s seen the company’s stock slide almost eight percent today, in its worst performance since October 2023. It’s also a sign of the times: as the New York Times reports, the whiff was due to slower-than-expected growth of its cloud-computing division, which delivers its AI tools to other businesses.

Okay, 0.1 percent is something, but I would have preferred the metaphor of the “flail” word to have been used in the paragraph begs for “flog,” “thrash,” and “whip.”

I used Sam AI-Man’s AI software to produce a good enough image of Googlers flailing. Frankly I don’t think Sam AI-Man’s system understands exactly what I wanted, but close enough for horseshoes in today’s world.

I noted this information and circled it. I love Gouda cheese. How can Google screw up cheese after its misstep with glue and cheese on pizza. Yo, Googlers. Check the cheese references.

Is Alphabet’s latest earnings result the canary in the coal mine? Should the AI industry brace for tougher days ahead as investors become increasingly skeptical of what the tech has to offer? Or are investors concerned over OpenAI’s ChatGPT overtaking Google’s search engine? Illustrating the drama, this week Google appears to have retroactively edited the YouTube video of a Super Bowl ad for its core AI model called Gemini, to remove an extremely obvious error the AI made about the popularity of gouda cheese.

Stalin revised history books. Google changes cheese references for its own advertising. But cheese?

The write up concludes with this, mostly from American high technology watching Guardian newspaper in the UK:

Although it’s still well insulated, Google’s advantages in search hinge on its ubiquity and entrenched consumer behavior,” Emarketer senior analyst Evelyn Mitchell-Wolf told The Guardian. This year “could be the year those advantages meaningfully erode as antitrust enforcement and open-source AI models change the game,” she added. “And Cloud’s disappointing results suggest that AI-powered momentum might be beginning to wane just as Google’s closed model strategy is called into question by Deepseek.”

Does this constitute the use of the word “flail”? Sure, but I like “thrash” a lot. And “wane” is good.

Stephen E Arnold, February 12, 2025

E-Casino: Gambling As a Service

November 15, 2024

Gambling is a vice, but it’s also big business. Many gambling practices are illegal and if you want to stay on the right side of the law, then you should make your future gambling business complies with all ordinances. For starters, you need to pay your taxes or the IRS will shut you down. Second, read Revanda Group’s review the “Best White Label Casino Solution Providers In 2024” and see what they offer.

Revpanda Group specializes in iGaming marketing services to assist companies acquire and retain players. They use affiliate marketing strategies to draw and connect traffic with the top brands in their industry. Their entire schtick is helping iGaming companies succeed and stay on the right side of the authorities. Their article is a quick how-to start a casino with the right partners.

Revpanda suggests using a white label casino solution, which is an out-of-the-box solution to start a business:

“…one company provides everything you need, including the casino platform itself, online casino software, payment gateways, an affiliate system, and technical support. Your main responsibilities include creating a logo for the casino website and partnering with an agency for content marketing your brand to potential customers. So, choosing a white label solution is easier than starting your own business from scratch….Simply put, a white label solution provides you with a ready-to-operate casino business whereby a third party will help you maintain and handle everyday operations.”

It almost sounds too good to be true, but Revpanda doesn’t make it sound like a get rich quick scam that are haunting YouTube ads. Revpanda explains that there is upfront cost and risks associate with owning a casino:

“One thing to note is that about 40% revenue share goes to the operator and 60% goes to the platform provider. In essence, white label casino solutions offer a turnkey approach for aspiring casino operators, allowing them to launch and market their business with minimal operational burdens, while sharing revenue with the platform provider.”

The casino-via-Door Dash also recommends potential online gambling parlor operators research their white label casino solution provider recommendations to discover the best fit. They discuss what consider when deciding what provider to work with, including licensing and regulation, game variety and quality, payment solutions, customization options, customer service and support, and mobile compatibility.

Yep, GaaS is a convenience.

Whitney Grace, November 15, 2024

Disinformation: Just a Click Away

November 11, 2024

Here is an interesting development. “CreationNetwork.ai Emerges As a Leading AI-Powered Platform, Integrating Over Twenty Two Tools,” reports HackerNoon. The AI aggregator uses Telegram plus other social media to push its service. Furthermore, the company is integrating crypto into its business plan. We expect these "blending" plays will become more common. The Chainwire press release says about this one:

“As an all-in-one solution for content creation, e-commerce, social media management, and digital marketing, CreationNetwork.ai combines 22+ proprietary AI-powered tools and 29+ platform integrations to deliver the most extensive digital ecosystem available. … CreationNetwork.ai’s suite of tools spans every facet of digital engagement, equipping users with powerful AI technologies to streamline operations, engage audiences, and optimize performance. Each tool is meticulously designed to enhance productivity and efficiency, making it easy to create, manage, and analyze content across multiple channels.”

See the write-up for a list of the tools included in CreationNetwork.ai, from AI Copywriter to Team-Powered Branding. The hefty roster of platform connections is also specified, including obvious players: all the major social media platforms, the biggest e-commerce platforms, and content creation tools like Canva, Grammarly, Adobe Express, Unsplash, and Dropbox. We learn:

“One of the most distinguishing features of CreationNetwork.ai is its extensive integration network. With over 29 integrations, users can synchronize their digital activities across major social media, e-commerce, and content platforms, providing centralized management and engagement capabilities. … This integration network empowers users to manage their brand presence across platforms from a single, unified dashboard, significantly enhancing efficiency and reach.”

Nifty. What a way to simplify digital processes for users. And to make it harder for new services to break into the market. But what groundbreaking platform would be complete without its own cryptocurrency? The write-up states:

“In preparation for its Initial Coin Offering (ICO), CreationNetwork.ai is launching a $750,000 CRNT Token Airdrop to reward early supporters and incentivize participation in the CreationNetwork.ai ecosystem. Qualified participants can secure their position by following CreationNetwork.ai’s social media accounts and completing the whitelist form available on the official website. This initiative highlights CreationNetwork.ai’s commitment to building a strong, engaged community.”

Online smart software is helpful in many ways.

Cynthia Murrell, November 11, 2024

What? Cloud Computing Costs Cut from Business Budgets

July 18, 2024

Many companies offload their data storage and computing needs to third parties aka cloud computing providers. Leveraging cloud computing was viewed as a great way to lower technology budgets, but with rising inflation and costs that perspective is changing. The BBC wrote an article about the changes in the cloud: “Are Rainy Days Ahead For Cloud Computing?”

Companies are reevaluating their investments in cloud computing, because the price tags are too high. The cloud was advertised as cheaper, easier, and faster. Businesses aren’t seeing any productive gains. Larger companies are considering dumping the cloud and rerouting their funds to self-hosting again. Clouding computing still has its benefits, especially for smaller companies who can’t invest in their technology infrastructure. Security is another concern:

“‘A key factor in our decision was that we have highly proprietary R&D data and code that must remain strictly secure,’ says Markus Schaal, managing director at the German firm. “If our investments in features, patches, and games were leaked, it would be an advantage to our competitors. While the public cloud offers security features, we ultimately determined we needed outright control over our sensitive intellectual property. "As our AI-assisted modelling tools advanced, we also required significantly more processing power that the cloud could not meet within budget.”

He adds:

“We encountered occasional performance issues during heavy usage periods and limited customization options through the cloud interface. Transitioning to a privately-owned infrastructure gave us full control over hardware purchasing, software installation, and networking optimized for our workloads.”

Cloud computing has seen its golden era, but it’s not disappearing. It’s still a useful computing tool, but won’t be the main infrastructure for companies that want to lower costs, stay within budget, secure their software, and other factors.

Whitney Grace, July 18, 2024

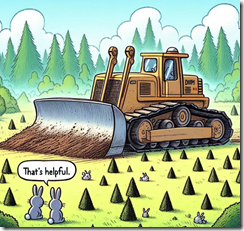

Can the Bezos Bulldozer Crush Temu, Shein, Regulators, and AI?

June 27, 2024

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

The question, to be fair, should be, “Can the Bezos-less bulldozer crush Temu, Shein, Regulators, Subscriptions to Alexa, and AI?” The article, which appeared in the “real” news online service Venture Beat, presents an argument suggesting that the answer is, “Yes! Absolutely.”

Thanks MSFT Copilot. Good bulldozer.

The write up “AWS AI Takeover: 5 Cloud-Winning Plays They’re [sic] Using to Dominate the Market” depends upon an Amazon Big Dog named Matt Wood, VP of AI products at AWS. The article strikes me as something drafted by a small group at Amazon and then polished to PR perfection. The reasons the bulldozer will crush Google, Microsoft, Hewlett Packard’s on-premises play, and the keep-on-searching IBM Watson, among others, are:

- Covering the numbers or logo of the AI companies in the “game”; for example, Anthropic, AI21 Labs, and other whale players

- Hitting up its partners, customers, and friends to get support for the Amazon AI wonderfulness

- Engineering AI to be itty bitty pieces one can use to build a giant AI solution capable of dominating D&B industry sectors like banking, energy, commodities, and any other multi-billion sector one cares to name

- Skipping the Google folly of dealing with consumers. Amazon wants the really big contracts with really big companies, government agencies, and non-governmental organizations.

- Amazon is just better at security. Those leaky S3 buckets are not Amazon’s problem. The customers failed to use Amazon’s stellar security tools.

Did these five points convince you?

If you did not embrace the spirit of the bulldozer, the Venture Beat article states:

Make no mistake, fellow nerds. AWS is playing a long game here. They’re not interested in winning the next AI benchmark or topping the leaderboard in the latest Kaggle competition. They’re building the platform that will power the AI applications of tomorrow, and they plan to power all of them. AWS isn’t just building the infrastructure, they’re becoming the operating system for AI itself.

Convinced yet? Well, okay. I am not on the bulldozer yet. I do hear its engine roaring and I smell the no-longer-green emissions from the bulldozer’s data centers. Also, I am not sure the Google, IBM, and Microsoft are ready to roll over and let the bulldozer crush them into the former rain forest’s red soil. I recall researching Sagemaker which had some AI-type jargon applied to that “smart” service. Ah, you don’t know Sagemaker? Yeah. Too bad.

The rather positive leaning Amazon write up points out that as nifty as those five points about Amazon’s supremacy in the AI jungle, the company has vision. Okay, it is not the customer first idea from 1998 or so. But it is interesting. Amazon will have infrastructure. Amazon will provide model access. (I want to ask, “For how long?” but I won’t.), and Amazon will have app development.

The article includes a table providing detail about these three legs of the stool in the bulldozer’s cabin. There is also a run down of Amazon’s recent media and prospect directed announcements. Too bad the article does not include hyperlinks to these documents. Oh, well.

And after about 3,300 words about Amazon, the article includes about 260 words about Microsoft and Google. That’s a good balance. Too bad IBM. You did not make the cut. And HP? Nope. You did not get an “Also participated” certificate.

Net net: Quite a document. And no mention of Sagemaker. The Bezos-less bulldozer just smashes forward. Success is in crushing. Keep at it. And that “they” in the Venture Beat article title: Shouldn’t “they” be an “it”?

Stephen E Arnold, June 27, 2024

Google Demos Its Reliability

June 5, 2024

This essay is the work of a dinobaby. Unlike some folks, no smart software improved my native ineptness.

This essay is the work of a dinobaby. Unlike some folks, no smart software improved my native ineptness.

Migrate everything to the cloud, they said. It is perfectly safe, we were told. And yet, “Google Cloud Accidentally Deletes $125 Billion Pension Fund’s Online Account,” reports Cyber Security News. Writer Dhivya reports a mistake in the setup process was to blame for the blunder. If it were not for a third-party backup, UniSuper’s profile might never have been recovered. We learn:

“A major mistake in setup caused Google Cloud and UniSuper to delete the financial service provider’s private cloud account. This event has caused many to worry about the security and dependability of cloud services, especially for big financial companies. The outage started in the blue, and UniSuper’s 620,000 members had no idea what was happening with their retirement funds.”

As it turns out, the funds themselves were just fine. But investors were understandably upset when they could not view updates. Together, the CEOs of Google Cloud and UniSuper dined on crow. Dhivya writes:

“According to the Guardian reports, the CEOs of UniSuper and Google Cloud, Peter Chun and Thomas Kurian, apologized for the failure together in a statement, which is not often done. … ‘UniSuper’s Private Cloud subscription was ultimately terminated due to an unexpected sequence of events that began with an inadvertent misconfiguration during provisioning,’ the two sources stated. ‘Google Cloud CEO Thomas Kurian has confirmed that the disruption was caused by an unprecedented sequence of events.’ ‘This is a one-time event that has never happened with any of Google Cloud’s clients around the world.’ ‘This really shouldn’t have happened,’ it said.”

At least everyone can agree on that. We are told UniSuper had two different backups, but they were also affected by the snafu. It was the backups kept by “another service provider” that allowed the hundreds of virtual machines, databases, and apps that made up UniSuper’s private cloud environment to be recovered. Eventually. The CEOs emphasized the herculean effort it took both Google Cloud and UniSuper technicians to make it happen. We hope they were well-paid. Naturally, both companies pledge to do keep this mistake from happening again. Great! But what about the next unprecedented, one-time screwup?

Let this be a reminder to us all: back up the data! Frequently and redundantly. One never knows when that practice will save the day.

Cynthia Murrell, June 5, 2024