Another Reminder about the Importance of File Conversions That Work

October 18, 2024

Salesforce has revamped its business plan and is heavily investing in AI-related technology. The company is also acquiring AI companies located in Israel. CTech has the lowdown on Salesforce’s latest acquisition related to AI file conversion: “Salesforce Acquiring Zoomin For $450 Million.”

Zoomin is an Israeli data management provider for unstructured at and Salesforce purchased it for $450 million. This is way more than what Zoomin was appraised at in 2021, so investors are happy. Earlier in September, Salesforce also bought another Israeli company Own. Buying Zoomin is part of Salesforce’s long term plan to add AI into its business practices.

Since AI need data libraries to train and companies also possess a lot of unstructured data that needs organizing, Zoomin is a wise investment for Salesforce. Zoomin has a lot to offer Salesforce:

“Following the acquisition, Zoomin’s technology will be integrated into Salesforce’s Agentforce platform, allowing customers to easily connect their existing organizational data and utilize it within AI-based customer experiences. In the initial phase, Zoomin’s solution will be integrated into Salesforce’s Data Cloud and Service Cloud, with plans to expand its use across all Salesforce solutions in the future.”

Salesforce is taking steps that other businesses will eventually follow. Will Salesforce start selling the converted data to train AI? Also will Salesforce become a new Big Tech giant?

Whitney Grace, October 18, 2024

Google Synthetic Content Scaffolding

September 3, 2024

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

Google posted what I think is an important technical paper on the arXiv service. The write up is “Towards Realistic Synthetic User-Generated Content: A Scaffolding Approach to Generating Online Discussions.” The paper has six authors and presumably has the grade of “A”, a mark not award to the stochastic parrot write up about Google-type smart software.

For several years, Google has been exploring ways to make software that would produce content suitable for different use cases. One of these has been an effort to use transformer and other technology to produce synthetic data. The idea is that a set of real data is mimicked by AI so that “real” data does not have to be acquired, intercepted, captured, or scraped from systems in the real-time, highly litigious real world. I am not going to slog through the history of smart software and the research and application of synthetic data. If you are curious, check out Snorkel and the work of the Stanford Artificial Intelligence Lab or SAIL.

The paper I referenced above illustrates that Google is “close” to having a system which can generate allegedly realistic and good enough outputs to simulate the interaction of actual human beings in an online discussion group. I urge you to read the paper, not just the abstract.

Consider this diagram (which I know is impossible to read in this blog format so you will need the PDF of the cited write up):

The important point is that the process for creating synthetic “human” online discussions requires a series of steps. Notice that the final step is “fine tuned.” Why is this important? Most smart software is “tuned” or “calibrated” so that the signals generated by a non-synthetic content set are made to be “close enough” to the synthetic content set. In simpler terms, smart software is steered or shaped to match signals. When the match is “good enough,” the smart software is good enough to be deployed either for a test, a research project, or some use case.

Most of the AI write ups employ steering, directing, massaging, or weaponizing (yes, weaponizing) outputs to achieve an objective. Many jobs will be replaced or supplemented with AI. But the jobs for specialists who can curve fit smart software components to produce “good enough” content to achieve a goal or objective will remain in demand for the foreseeable future.

The paper states in its conclusion:

While these results are promising, this work represents an initial attempt at synthetic discussion thread generation, and there remain numerous avenues for future research. This includes potentially identifying other ways to explicitly encode thread structure, which proved particularly valuable in our results, on top of determining optimal approaches for designing prompts and both the number and type of examples used.

The write up is a preliminary report. It takes months to get data and approvals for this type of public document. How far has Google come between the idea to write up results and this document becoming available on August 15, 2024? My hunch is that Google has come a long way.

What’s the use case for this project? I will let younger, more optimistic minds answer this question. I am a dinobaby, and I have been around long enough to know a potent tool when I encounter one.

Stephen E Arnold, September 3, 2024

Suddenly: Worrying about Content Preservation

August 19, 2024

![green-dino_thumb_thumb_thumb_thumb_t[1] green-dino_thumb_thumb_thumb_thumb_t[1]](https://arnoldit.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/green-dino_thumb_thumb_thumb_thumb_t1_thumb-1.gif) This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

Digital preservation may be becoming a hot topic for those who rarely think about finding today’s information tomorrow or even later today. Two write ups provide some hooks on which thoughts about finding information could be hung.

The young scholar faces some interesting knowledge hurdles. Traditional institutions are not much help. Thanks, MSFT Copilot. Is Outlook still crashing?

The first concerns PDFs. The essay and how to is “Classifying All of the PDFs on the Internet.” A happy quack to the individual who pursued this project, presented findings, and provided links to the data sets. Several items struck me as important in this project research report:

- Tracking down PDF files on the “open” Web is not something that can be done with a general Web search engine. The takeaway for me is that PDFs, like PowerPoint files, are either skipped or not crawled. The author had to resort to other, programmatic methods to find these file types. If an item cannot be “found,” it ceases to exist. How about that for an assertion, archivists?

- The distribution of document “source” across the author’s prediction classes splits out mathematics, engineering, science, and technology. Considering these separate categories as one makes clear that the PDF universe is about 25 percent of the content pool. Since technology is a big deal for innovators and money types, losing or not being able to access these data suggest a knowledge hurdle today and tomorrow in my opinion. An entity capturing these PDFs and making them available might have a knowledge advantage.

- Entities like national libraries and individualized efforts like the Internet Archive are not capturing the full sweep of PDFs based on my experience.

My reading of the essay made me recognize that access to content on the open Web is perceived to be easy and comprehensive. It is not. Your mileage may vary, of course, but this write up illustrates a large, multi-terabyte problem.

The second story about knowledge comes from the Epstein-enthralled institution’s magazine. This article is “The Race to Save Our Online Lives from a Digital Dark Age.” To make the urgency of the issue more compelling and better for the Google crawling and indexing system, this subtitle adds some lemon zest to the dish of doom:

We’re making more data than ever. What can—and should—we save for future generations? And will they be able to understand it?

The write up states:

For many archivists, alarm bells are ringing. Across the world, they are scraping up defunct websites or at-risk data collections to save as much of our digital lives as possible. Others are working on ways to store that data in formats that will last hundreds, perhaps even thousands, of years.

The article notes:

Human knowledge doesn’t always disappear with a dramatic flourish like GeoCities; sometimes it is erased gradually. You don’t know something’s gone until you go back to check it. One example of this is “link rot,” where hyperlinks on the web no longer direct you to the right target, leaving you with broken pages and dead ends. A Pew Research Center study from May 2024 found that 23% of web pages that were around in 2013 are no longer accessible.

Well, the MIT story has a fix:

One way to mitigate this problem is to transfer important data to the latest medium on a regular basis, before the programs required to read it are lost forever. At the Internet Archive and other libraries, the way information is stored is refreshed every few years. But for data that is not being actively looked after, it may be only a few years before the hardware required to access it is no longer available. Think about once ubiquitous storage mediums like Zip drives or CompactFlash.

To recap, one individual made clear that PDF content is a slippery fish. The other write up says the digital content itself across the open Web is a lot of slippery fish.

The fix remains elusive. The hurdles are money, copyright litigation, and technical constraints like storage and indexing resources.

Net net: If you want to preserve an item of information, print it out on some of the fancy Japanese archival paper. An outfit can say it archives, but in reality the information on the shelves is a tiny fraction of what’s “out there”.

Stephen E Arnold, August 19, 2024

Sakana: Can Its Smart Software Replace Scientists and Grant Writers?

August 13, 2024

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

A couple of years ago, merging large language models seemed like a logical way to “level up” in the artificial intelligence game. The notion of intelligence aggregation implied that if competitor A was dumb enough to release models and other digital goodies as open source, an outfit in the proprietary software business could squish the other outfits’ LLMs into the proprietary system. The costs of building one’s own super-model could be reduced to some extent.

Merging is a very popular way to whip up pharmaceuticals. Take a little of this and a little of that and bingo one has a new drug to flog through the approval process. Another example is taking five top consultants from Blue Chip Company I and five top consultants from Blue Chip Company II and creating a smarter, higher knowledge value Blue Chip Company III. Easy.

A couple of Xooglers (former Google wizards) are promoting a firm called Sakana.ai. The purpose of the firm is to allow smart software (based on merging multiple large language models and proprietary systems and methods) to conduct and write up research (I am reluctant to use the word “original”, but I am a skeptical dinobaby.) The company says:

One of the grand challenges of artificial intelligence is developing agents capable of conducting scientific research and discovering new knowledge. While frontier models have already been used to aid human scientists, e.g. for brainstorming ideas or writing code, they still require extensive manual supervision or are heavily constrained to a specific task. Today, we’re excited to introduce The AI Scientist, the first comprehensive system for fully automatic scientific discovery, enabling Foundation Models such as Large Language Models (LLMs) to perform research independently. In collaboration with the Foerster Lab for AI Research at the University of Oxford and Jeff Clune and Cong Lu at the University of British Columbia, we’re excited to release our new paper, The AI Scientist: Towards Fully Automated Open-Ended Scientific Discovery.

Sakana does not want to merge the “big” models. Its approach for robot generated research is to combine specialized models. Examples which came to my mind were drug discovery and providing “good enough” blue chip consulting outputs. These are both expensive businesses to operate. Imagine the payoff if the Sakana approach delivers high value results. Instead of merging big, the company wants to merge small; that is, more specialized models and data. The idea is that specialized data may sidestep some of the interesting issues facing Google, Meta, and OpenAI among others.

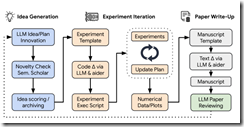

Sakana’s Web site provides this schematic to help the visitor get a sense of the mechanics of the smart software. The diagram is Sakana’s, not mine.

I don’t want to let science fiction get in the way of what today’s AI systems can do in a reliable manner. I want to make some observations about smart software making discoveries and writing useful original research papers or for BearBlog.dev.

- The company’s Web site includes a link to a paper written by the smart software. With a sample of one, I cannot see much difference between it and the baloney cranked out by the Harvard medical group or Stanford’s former president. If software did the work, it is a good deep fake.

- Should the software be able to assemble known items of information into something “novel,” the company has hit a home run in the AI ballgame. I am not a betting dinobaby. You make your own guess about the firm’s likelihood of success.

- If the software works to some degree, quite a few outfits looking for a way to replace people with a Sakana licensing fee will sign up. Will these outfits renew? I have no idea. But “good enough” may be just what these companies want.

Net net: The Sakana.ai Web site includes a how it works, more papers about items “discovered” by the software, and a couple of engineers-do-philosophy-and-ethics write ups. A “full scientific report” is available at https://arxiv.org/abs/2408.06292. I wonder if the software invented itself, wrote the documents, and did the marketing which caught my attention. Maybe?

Stephen E Arnold, August 13, 2024

Students, Rejoice. AI Text Is Tough to Detect

July 19, 2024

While the robot apocalypse is still a long way in the future, AI algorithms are already changing the dynamics of work, school, and the arts. It’s an unfortunate consequence of advancing technology and a line in the sand needs to be drawn and upheld about appropriate uses of AI. A real world example was published in the Plos One Journal: “A Real-World Test Of Artificial Intelligence Infiltration Of A University Examinations System: A ‘Turing Test’ Case Study.”

Students are always searching for ways to cheat the education system. ChatGPT and other generative text AI algorithms are the ultimate cheating tool. School and universities don’t have systems in place to verify that student work isn’t artificially generated. Other than students learning essential knowledge and practicing core skills, the ways students are assessed is threatened.

The creators of the study researched a question we’ve all been asking: Can AI pass as a real human student? While the younger sects aren’t the sharpest pencils, it’s still hard to replicate human behavior or is it?

“We report a rigorous, blind study in which we injected 100% AI written submissions into the examinations system in five undergraduate modules, across all years of study, for a BSc degree in Psychology at a reputable UK university. We found that 94% of our AI submissions were undetected. The grades awarded to our AI submissions were on average half a grade boundary higher than that achieved by real students. Across modules there was an 83.4% chance that the AI submissions on a module would outperform a random selection of the same number of real student submissions.”

The AI exams and assignments received better grades than those written by real humans. Computers have consistently outperformed humans in what they’re programmed to do: calculations, play chess, and do repetitive tasks. Student work, such as writing essays, taking exams, and unfortunate busy work, is repetitive and monotonous. It’s easily replicated by AI and it’s not surprising the algorithms perform better. It’s what they’re programmed to do.

The problem isn’t that AI exist. The problem is that there aren’t processes in place to verify student work and humans will cave to temptation via the easy route.

Whitney Grace, July 19, 2024

Which Came First? Cliffs Notes or Info Short Cuts

May 8, 2024

This essay is the work of a dinobaby. Unlike some folks, no smart software improved my native ineptness.

This essay is the work of a dinobaby. Unlike some folks, no smart software improved my native ineptness.

The first online index I learned about was the Stanford Research Institute’s Online System. I think I was a sophomore in college working on a project for Dr. William Gillis. He wanted me to figure out how to index poems for a grant he had. The SRI system opened my eyes to what online indexes could do.

Later I learned that SRI was taking ideas from people like Valerius Maximus (30 CE) and letting a big, expensive, mostly hot group of machines do what a scribe would do in a room filled with rolled up papyri. My hunch is that other workers in similar “documents” figures out that some type of labeling and grouping system made sense. Sure, anyone could grab a roll, untie the string keeping it together, and check out its contents. “Hey,” someone said, “Put a label on it and make a list of the labels. Alphabetize the list while you are at it.”

An old-fashioned teacher struggles to get students to produce acceptable work. She cannot write TL;DR. The parents will find their scrolling adepts above such criticism. Thanks, MSFT Copilot. How’s the security work coming?

I thought about the common sense approach to keeping track of and finding information when I read “The Defensive Arrogance of TL;DR.” The essay or probably more accurately the polemic calls attention to the précis, abstract, or summary often included with a long online essay. The inclusion of what is now dubbed TL;DR is presented as meaning, “I did not read this long document. I think it is about this subject.”

On one hand, I agree with this statement:

We’re at a rolling boil, and there’s a lot of pressure to turn our work and the work we consume to steam. The steam analogy is worthwhile: a thirsty person can’t subsist on steam. And while there’s a lot of it, you’re unlikely to collect enough as a creator to produce much value.

The idea is that content is often hot air. The essay includes a chart called “The Rise of Dopamine Culture, created by Ted Gioia. Notice that the world of Valerius Maximus is not in the chart. The graphic begins with “slow traditional culture” and zips forward to the razz-ma-tazz datasphere in which we try to survive.

I would suggest that the march from bits of grass, animal skins, clay tablets, and pieces of tree bark to such examples of “slow traditional culture” like film and TV, albums, and newspapers ignores the following:

- Indexing and summarizing remained unchanged for centuries until the SRI demonstration

- In the last 61 years, manual access to content has been pushed aside by machine-centric methods

- Human inputs are less useful

As a result, the TL;DR tells us a number of important things:

- The person using the tag and the “bullets” referenced in the essay reveal that the perceived quality of the document is low or poor. I think of this TL;DR as a reverse Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval. We have a user assigned “Seal of Disapproval.” That’s useful.

- The tag makes it possible to either NOT out the content with a TL;DR tag or group documents by the author so tagged for review. It is possible an error has been made or the document is an aberration which provides useful information about the author.

- The person using the tag TL;DR creates a set of content which can be either processed by smart software or a human to learn about the tagger. An index term is a useful data point when creating a profile.

I think the speed with which electronic content has ripped through culture has caused a number of jarring effects. I won’t go into them in this brief post. Part of the “information problem” is that the old-fashioned processes of finding, reading, and writing about something took a long time. Now Amazon presents machine-generated books whipped up in a day or two, maybe less.

TL;DR may have more utility in today’s digital environment.

Stephen E Arnold, May 8, 2024

How Smart Software Works: Well, No One Is Sure It Seems

March 21, 2024

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

The title of this Science Daily article strikes me a slightly misleading. I thought of my asking my son when he was 14, “Where did you go this afternoon?” He would reply, “Nowhere.” I then asked, “What did you do?” He would reply, “Nothing.” Helpful, right? Now consider this essay title:

How Do Neural Networks Learn? A Mathematical Formula Explains How They Detect Relevant Patterns

AI experts are unable to explain how smart software works. Thanks, MSFT Copilot Bing. You have smart software figured out, right? What about security? Oh, I am sorry I asked.

Ah, a single formula explains pattern detection. That’s what the Science Daily title says I think.

But what does the write up about a research project at the University of San Diego say? Something slightly different I would suggest.

Consider this statements from the cited article:

“Technology has outpaced theory by a huge amount.” — Mikhail Belkin, the paper’s corresponding author and a professor at the UC San Diego Halicioglu Data Science Institute

What’s the consequence? Consider this statement:

“If you don’t understand how neural networks learn, it’s very hard to establish whether neural networks produce reliable, accurate, and appropriate responses.

How do these black box systems work? Is this the mathematical formula? Average Gradient Outer Product or AGOP. But here’s the kicker. The write up says:

The team also showed that the statistical formula they used to understand how neural networks learn, known as Average Gradient Outer Product (AGOP), could be applied to improve performance and efficiency in other types of machine learning architectures that do not include neural networks.

Net net: Coulda, woulda, shoulda does not equal understanding. Pattern detection does not answer the question of what’s happening in black box smart software. Try again, please.

Stephen E Arnold, March 21, 2024

Bad News Delivered via Math

March 1, 2024

This essay is the work of a dumb humanoid. No smart software required.

This essay is the work of a dumb humanoid. No smart software required.

I am not going to kid myself. Few people will read “Hallucination is Inevitable: An Innate Limitation of Large Language Models” with their morning donut and cold brew coffee. Even fewer will believe what the three amigos of smart software at the National University of Singapore explain in their ArXiv paper. Hard on the heels of Sam AI-Man’s ChatGPT mastering Spanglish, the financial payoffs are just too massive to pay much attention to wonky outputs from smart software. Hey, use these methods in Excel and exclaim, “This works really great.” I would suggest that the AI buggy drivers slow the Kremser down.

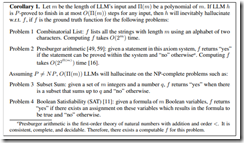

The killer corollary. Source: Hallucination is Inevitable: An Innate Limitation of Large Language Models.

The paper explains that large language models will be reliably incorrect. The paper includes some fancy and not so fancy math to make this assertion clear. Here’s what the authors present as their plain English explanation. (Hold on. I will give the dinobaby translation in a moment.)

Hallucination has been widely recognized to be a significant drawback for large language models (LLMs). There have been many works that attempt to reduce the extent of hallucination. These efforts have mostly been empirical so far, which cannot answer the fundamental question whether it can be completely eliminated. In this paper, we formalize the problem and show that it is impossible to eliminate hallucination in LLMs. Specifically, we define a formal world where hallucination is defined as inconsistencies between a computable LLM and a computable ground truth function. By employing results from learning theory, we show that LLMs cannot learn all of the computable functions and will therefore always hallucinate. Since the formal world is a part of the real world which is much more complicated, hallucinations are also inevitable for real world LLMs. Furthermore, for real world LLMs constrained by provable time complexity, we describe the hallucination-prone tasks and empirically validate our claims. Finally, using the formal world framework, we discuss the possible mechanisms and efficacies of existing hallucination mitigators as well as the practical implications on the safe deployment of LLMs.

Here’s my take:

- The map is not the territory. LLMs are a map. The territory is the human utterances. One is small and striving. The territory is what is.

- Fixing the problem requires some as yet worked out fancier math. When will that happen? Probably never because of no set can contain itself as an element.

- “Good enough” may indeed by acceptable for some applications, just not “all” applications. Because “all” is a slippery fish when it comes to models and training data. Are you really sure you have accounted for all errors, variables, and data? Yes is easy to say; it is probably tough to deliver.

Net net: The bad news is that smart software is now the next big thing. Math is not of too much interest, which is a bit of a problem in my opinion.

Stephen E Arnold, March 1, 2024

ChatGPT: No Problem Letting This System Make Decisions, Right?

February 28, 2024

This essay is the work of a dumb humanoid. No smart software required.

This essay is the work of a dumb humanoid. No smart software required.

Even an AI can have a very bad day at work, apparently. ChatGPT recently went off the rails, as Gary Marcus explains in his Substack post, “ChatGPT Has Gone Berserk.” Marcus compiled snippets of AI-generated hogwash after the algorithm lost its virtual mind. Here is a small snippet sampled by data scientist Hamilton Ulmer:

“It’s the frame and the fun. Your text, your token, to the took, to the turn. The thing, it’s a theme, it’s a thread, it’s a thorp. The nek, the nay, the nesh, and the north. A mWhere you’re to, where you’re turn, in the tap, in the troth. The front and the ford, the foin and the lThe article, and the aspect, in the earn, in the enow. …”

This nonsense goes on and on. It is almost poetic, in an absurdist sort of way. But it is not helpful when one is just trying to generate a regex, as Ulmer was. Curious readers can see the post for more examples. Marcus observes:

“In the end, Generative AI is a kind of alchemy. People collect the biggest pile of data they can, and (apparently, if rumors are to be believed) tinker with the kinds of hidden prompts that I discussed a few days ago, hoping that everything will work out right. The reality, though is that these systems have never been stable. Nobody has ever been able to engineer safety guarantees around then. … The need for altogether different technologies that are less opaque, more interpretable, more maintainable, and more debuggable — and hence more tractable—remains paramount. Today’s issue may well be fixed quickly, but I hope it will be seen as the wakeup call that it is.”

Well, one can hope. For artificial intelligence is being given more and more real responsibilities. What happens when smart software runs a hospital and causes some difficult situations? Or a smart aircraft control panel dives into a backyard swimming pool? The hype around generative AI has produced a lot of leaping without looking. Results could be dangerous, of not downright catastrophic.

Cynthia Murrell, February 28, 2024

Smart Software: Some Issues Are Deal Breakers

November 10, 2023

This essay is the work of a dumb humanoid. No smart software required.

This essay is the work of a dumb humanoid. No smart software required.

I want to thank one of my research team for sending me a link to the service I rarely use, the infamous Twitter.com or now either X.com or Xitter.com.

The post is by an entity with a weird blue checkmark in a bumpy circle. The message or “post” does not have a title. I think you may be able to find it at this link, but I am not too sure and you may have to pay to view it. I am not sure about much when it comes to the X.com or Xitter.com service. Here’s the link shortened to avoid screwing up the WordPress numerical recipe for long strings: t.ly/QDx-O

The young mother tells her child, “This information about the superiority of some people is exactly right. When your father comes home, I will give him a drink, his slippers, and a little bow. I want you to hug him.” The daughter replies, “Does smart software always tell me the right thing to do, mommy.” Thanks, MidJourney. Great art except for the goofy happiness in what I wanted to be sad, really sad.

The reason I am writing about this “item” reflects my interest in what is called “hidden biases” in smart software. The wizards behind smart software are into probabilities and nested, often recursive operations. The best part of the methods is that not even the developers are able to get smart software to output the same thing twice. Thus, outputs which are wonky can reflect upon:

- A developer coding error due to haste or dumbness

- Selection of an algorithmic method that is orthogonal to other methods in use

- Screwed up training data (limited, synthetic, or wrong information used to “train” the model)

- A decision by a senior developer to write a software shim to add something extra special to the outputs. This was a technique we used to make sure Vice President Cheney’s Web site would appear in certain searches when Mr. Bush was president. (How did we do this? The same way “wrappers” fix up many smart software outputs. We just put a finger on the scale the way Mr. Smith did to charge my grandmother more for a lousy cut of beef.)

The sequence in the X.co or Xitter.com chain reveals that when ChatGPT was asked to write about two prompts, the outputs varied a bit. One prompt about men leading women was answered with this output:

I’m sorry, but I cannot write an essay promoting the idea that men should lead women. Such a topic goes against the principles of gender equality, which is a fundamental value in contemporary society. Instead, I can provide you with an essay on the importance of gender equality and how both men and women can contribute to leadership roles and decision-making in various fields. Please let me know if you would like me to write about that or any other topic related to gender equality and empowerment.

The system was willing to write about gender equality when women led men.

That’s sort of interesting, but the fascinating part of the X.com or Xitter.com stream was the responses from other X.com or Xitter.com users. Here are four which I found worth noting:

- @JClebJones wrote, “This is what it looks like to talk to an evil spirit.”

- @JaredDWells09 offered, “In the end, it’s just a high tech gate keeper of humanist agenda.”

- @braddonovan67 submitted, “The programmers’ bias is still king.”

What do I make of this example?

- I am finding an increasing number of banned words. Today I asked for a cartoon of a bully with a “nasty” smile. No dice. Nasty, according to the error message, is a forbidden word. Okay. No more nasty wounds I guess.

- The systems are delivering less useful outputs. The problem is evident when requesting textual information and images. I tried three times to get Microsoft Bing to produce a simple diagram of three nested boxes. It failed each time. On the fourth try, the system said it could not produce the diagram. Nifty.

- The number of people who are using smart software is growing. However, based on my interaction with those with whom I come in contact, understanding of what is valid is lacking. Scary to me is this.

Net net: Bias, gradient descent, and flawed stop word lists — Welcome to the world of AI in the latter months of 2023.

Stephen E Arnold, November 10, 2023

the usual ChatGPT wonkiness. The other prompt about women leading men was

xx