An Ed Critique That Pans the Sundar & Prabhakar Comedy Act

August 16, 2024

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

I read Ed.

Ed refers to Edward Zitron, the thinker behind Where’s Your Ed At. The write up which caught my attention is “Monopoly Money.” I think that Ed’s one-liners will not be incorporated into the Sundar & Prabhakar comedy act. The flubbed live demos are knee slappers, but Ed’s write up is nipping at the heels of the latest Googley gaffe.

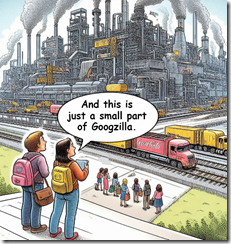

Young people are keen observers of certain high-technology companies. What happens if one of the giants becomes virtual and moves to a Dubai-type location? Who has jurisdiction? Regulatory enforcement delayed means big high-tech outfits are more portable than old-fashioned monopolies. Thanks, MSFT Copilot. Big industrial images are clearly a core competency you have.

Ed’s focus is on the legal decision which concluded that the online advertising company is a monopoly in “general text advertising.” The essay states:

The ruling precisely explains how Google managed to limit competition and choice in the search and ad markets. Documents obtained through discovery revealed the eye-watering amounts Google paid to Samsung ($8 billion over four years) and Apple ($20 billion in 2022 alone) to remain the default search engine on their devices, as well as Mozilla (around $500 million a year), which (despite being an organization that I genuinely admire, and that does a lot of cool stuff technologically) is largely dependent on Google’s cash to remain afloat.

Ed notes:

Monopolies are a big part of why everything feels like it stopped working.

Ed is on to something. The large technology outfits in the US control online. But one of the downstream consequences of what I call the Silicon Valley way or the Googley approach to business is that other industries and market sectors have watched how modern monopolies work. The result is that concentration of power has not been a regulatory priority. The role of data aggregation has been ignored. As a result, outfits like Kroger (a grocery company) is trying to apply Googley tactics to vegetables.

Ed points out:

Remember when “inflation” raised prices everywhere? It’s because the increasingly-dwindling amount of competition in many consumer goods companies allowed them to all raise their prices, gouging consumers in a way that should have had someone sent to jail rather than make $19 million for bleeding Americans dry. It’s also much, much easier for a tech company to establish one, because they often do so nestled in their own platforms, making them a little harder to pull apart. One can easily say “if you own all the grocery stores in an area that means you can control prices of groceries,” but it’s a little harder to point at the problem with the tech industry, because said monopolies are new, and different, yet mostly come down to owning, on some level, both the customer and those selling to the customer.

Blue chip consulting firms flip this comment around. The points Ed makes are the recommendations and tactics the would-be monopolists convert to action plans. My reaction is, “Thanks, Silicon Valley. Nice contribution to society.”

Ed then gets to artificial intelligence, definitely a hot topic. He notes:

Monopolies are inherently anti-consumer and anti-innovation, and the big push toward generative AI is a blatant attempt to create another monopoly — the dominance of Large Language Models owned by Microsoft, Amazon, Google and Meta. While this might seem like a competitive marketplace, because these models all require incredibly large amounts of cloud compute and cash to both train and maintain, most companies can’t really compete at scale.

Bingo.

I noted this Ed comment about AI too:

This is the ideal situation for a monopolist — you pay them money for a service and it runs without you knowing how it does so, which in turn means that you have no way of building your own version. This master plan only falls apart when the “thing” that needs to be trained using hardware that they monopolize doesn’t actually provide the business returns that they need to justify its existence.

Ed then makes a comment which will cause some stakeholders to take a breath:

As I’ve written before, big tech has run out of hyper-growth markets to sell into, leaving them with further iterations of whatever products they’re selling you today, which is a huge problem when big tech is only really built to rest on its laurels. Apple, Microsoft and Amazon have at least been smart enough to not totally destroy their own products, but Meta and Google have done the opposite, using every opportunity to squeeze as much revenue out of every corner, making escape difficult for the customer and impossible for those selling to them. And without something new — and no, generative AI is not the answer — they really don’t have a way to keep growing, and in the case of Meta and Google, may not have a way to sustain their companies past the next decade. These companies are not built to compete because they don’t have to, and if they’re ever faced with a force that requires them to do good stuff that people like or win a customer’s love, I’m not sure they even know what that looks like.

Viewed from a Googley point of view, these high-technology outfits are doing what is logical. That’s why the Google advertisement for itself troubled people. The person writing his child willfully used smart software. The fellow embodied a logical solution to the knotty problem of feelings and appropriate behavior.

Ed suggests several remedies for the Google issue. These make sense, but the next step for Google will be an appeal. Appeals take time. US government officials change. The appetite to fight legions of well resourced lawyers can wane. The decision reveals some interesting insights into the behavior of Google. The problem now is how to alter that behavior without causing significant market disruption. Google is really big, and changes can have difficult-to-predict consequences.

The essay concludes:

I personally cannot leave Google Docs or Gmail without a significant upheaval to my workflow — is a way that they reinforce their monopolies. So start deleting sh*t. Do it now. Think deeply about what it is you really need — be it the accounts you have and the services you need — and take action. They’re not scared of you, and they should be.

Interesting stance.

Several observations:

- Appeals take time. Time favors outfits like losers of anti-trust cases.

- Google can adapt and morph. The size and scale equip the Google in ways not fathomable to those outside Google.

- Google is not Standard Oil. Google is like AT&T. That break up resulted in reconsolidation and two big Baby Bells and one outside player. So a shattered Google may just reassemble itself. The fancy word for this is emergent.

Ed hits some good points. My view is that the Google fumbles forward putting the Sundar & Prabhakar Comedy Act in every city the digital wagon can reach.

Stephen E Arnold, August 16, 2024