If Math Is Running Out of Problems, Will AI Help Out the Humans?

July 26, 2024

This essay is the work of a dinobaby. Unlike some folks, no smart software improved my native ineptness.

This essay is the work of a dinobaby. Unlike some folks, no smart software improved my native ineptness.

I read “Math Is Running Out of Problems.” The write up appeared in Medium and when I clicked I was not asked to join, pay, or turn a cartwheel. (Does Medium think 80-year-old dinobabies can turn cartwheels? The answer is, “Hey, doofus, if you want to read Medium articles pay up.)

Thanks, MSFT Copilot. Good enough, just like smart security software.

I worked through the free essay, which is a reprise of an earlier essay on the topic of running out of math problems. These reason that few cared about the topic is that most people cannot make change. Thinking about a world without math problems is an intellectual task which takes time from scamming the elderly, doom scrolling, generating synthetic information, or watching reruns of I Love Lucy.

The main point of the essay in my opinion is:

…take a look at any undergraduate text in mathematics. How many of them will mention recent research in mathematics from the last couple decades? I’ve never seen it.

New and math problems is an oxymoron.

I think the author is correct. As specialization becomes more desirable to a person, leaving the rest of the world behind is a consequence. But the issue arises in other disciplines. Consider artificial intelligence. That jazzy phrase embraces a number of mathematical premises, but it boils down to a few chestnuts, roasted, seasoned, and mixed with some interesting ethanols. (How about that wild and crazy Sir Thomas Bayes?)

My view is that as the apparent pace of information flow erodes social and cultural structures, the quest for “new” pushes a frantic individual to come up with a novelty. The problem with a novelty is that it takes one’s eye off the ball and ultimately the game itself. The present state of affairs in math was evident decades ago.

What’s interesting is that this issue is not new. In the early 1980s, Dialog Information Services hosted a mathematics database called xxx. The person representing the MATHFILE database (now called MathSciNet) told me in 1981:

We are having a difficult time finding people to review increasingly narrow and highly specialized papers about an almost unknown area of mathematics.

Flash forward to 2024. Now this problem is getting attention in 2024 and no one seems to care?

Several observations:

- Like smart software, maybe humans are running out of high-value information? Chasing ever smaller mathematical “insights” may be a reminder that humans and their vaunted creativity has limits, hard limits.

- If the premise of the paper is correct, the issue should be evident in other fields as well. I would suggest the creation of a “me too” index. The idea is that for a period of history, one can calculate how many knock off ideas grab the coat tails of an innovation. My hunch is that the state of most modern technical insight is high on the me too index. No, I am not counting “original” TikTok-type information objects.

- The fragmentation which seems apparent to me in mathematics and that interesting field of mathematical physics mirrors the fragmentation of certain cultural precepts; for example, ethical behavior. Why is everything “so bad”? The answer is, “Specialization.”

Net net: The pursuit of the ever more specialized insight hastens the erosion of larger ideas and cultural knowledge. We have come a long way in four decades. The direction is clear. It is not just a math problem. It is a now problem and it is pervasive. I want a hat that says, “I’m glad I’m old.”

Stephen E Arnold, July 26, 2024

A Discernment Challenge for Those Who Are Dull Normal

June 24, 2024

This essay is the work of a dinobaby. Unlike some folks, no smart software improved my native ineptness.

This essay is the work of a dinobaby. Unlike some folks, no smart software improved my native ineptness.

Techradar, an online information service, published “Ahead of GPT-5 Launch, Another Test Shows That People Cannot Distinguish ChatGPT from a Human in a Conversation Test — Is It a Watershed Moment for AI?” The headline implies “change everything” rhetoric, but that is routine AI jargon-hype.

Once again, academics who are unable to land a job in a “real” smart software company studied the work of their former colleagues who make a lot more money than those teaching do. Well, what do academic researchers do when they are not sitting in the student union or the snack area in the lab whilst waiting for a graduate student to finish a task? In my experience, some think about their CVs or résumés. Others ponder the flaws in a commercial or allegedly commercial product or service.

A young shopper explains that the outputs of egg laying chickens share a similarity. Insightful observation from a dumb carp. Thanks, MSFT Copilot. How’s that Recall project coming along?

The write up reports:

The Department of Cognitive Science at UC San Diego decided to see how modern AI systems fared and evaluated ELIZA (a simple rules-based chatbot from the 1960’s included as a baseline in the experiment), GPT-3.5, and GPT-4 in a controlled Turing Test. Participants had a five-minute conversation with either a human or an AI and then had to decide whether their conversation partner was human.

Here’s the research set up:

In the study, 500 participants were assigned to one of five groups. They engaged in a conversation with either a human or one of the three AI systems. The game interface resembled a typical messaging app. After five minutes, participants judged whether they believed their conversation partner was human or AI and provided reasons for their decisions.

And what did the intrepid academics find? Factoids that will get them a job at a Perplexity-type of company? Information that will put smart software into focus for the elected officials writing draft rules and laws to prevent AI from making The Terminator come true?

The results were interesting. GPT-4 was identified as human 54% of the time, ahead of GPT-3.5 (50%), with both significantly outperforming ELIZA (22%) but lagging behind actual humans (67%). Participants were no better than chance at identifying GPT-4 as AI, indicating that current AI systems can deceive people into believing they are human.

What does this mean for those labeled dull normal, a nifty term applied to some lucky people taking IQ tests. I wanted to be a dull normal, but I was able to score in the lowest possible quartile. I think it was called dumb carp. Yes!

Several observations to disrupt your clear thinking about smart software and research into how the hot dogs are made:

- The smart software seems to have stalled. Our tests of You.com which allows one to select which object models parrots information, it is tough to differentiate the outputs. Cut from the same transformer cloth maybe?

- Those judging, differentiating, and testing smart software outputs can discern differences if they are way above dull normal or my classification dumb carp. This means that indexing systems, people, and “new” models will be bamboozled into thinking what’s incorrect is a-okay. So much for the informed citizen.

- Will the next innovation in smart software revolutionize something? Yep, some lucky investors.

Net net: Confusion ahead for those like me: Dumb carp. Dull normals may be flummoxed. But those super-brainy folks have a chance to rule the world. Bust out the party hats and little horns.

Stephen E Arnold, June 24, 2024

Think You Know Which Gen Z Is What?

June 7, 2024

This essay is the work of a dinobaby. Unlike some folks, no smart software improved my native ineptness.

This essay is the work of a dinobaby. Unlike some folks, no smart software improved my native ineptness.

I had to look this up? A Gen Z was born when? A Gen Z was born between 1981 and 1996. In 2024, a person aged 28 to 43 is, therefore, a Gen Z. Who knew? The definition is important. I read “Shocking Survey: Nearly Half of Gen Z Live a Double Life Online.” What do you know? A nice suburb, lots of Gen Zs, and half of these folks are living another life online. Go to one of those hip new churches with kick-back names and half of the Gen Zs heads bowed in prayer are living a double life. For whom do those folks pray? Hit the golf club and look at the polo shirt clad, self-satisfied 28 to 43 year olds. Which self is which? The chat room Dark Web person or a happy golfer enjoying the 19th hole?

Someone who is older is jumping to conclusions. Those vans probably contain office supplies, toxic waste, or surplus government equipment. No one would take Gen Zs out of the flow, would they? Thanks, MSFT. Do you have Gen Zs working on your superlative security systems?

The write up reports:

A survey of 2,000 Americans, split evenly by generation, found that 46% of Gen Z respondents feel their personality online vastly differs from how they present themselves in the real world.

Only eight percent of the baby boomers are different online. New flash: If you ever meet me, I am the same person writing these blog posts. As an 80-year-old dinobaby, I don’t need another persona to baffle the brats in the social media sewer. I just avoid the sewer and remain true to my ageing self.

The write up also provides this glimpse into the hearts and souls of those 28 to 43:

Specifically, 31% of Gen Z respondents admitted their online world is a secret from family

That’s good. These Gen Zs can keep a secret. But why? What are they trying to hide from their family, friends, and co-workers? I can guess but won’t.

If you work with a Gen Z, here’s an allegedly valid factoid from the survey:

53% of Gen Zers said it’s easier to express themselves online than offline.

Want another? Too bad. Here’s a winner insight:

68 percent of Gen Zs sometimes feel a disconnect between who they are online and offline.

I think I took a psychology class when I was a freshman in college. I recall learning about a mental disorder with inconsistent or contradictory elements. Are Gen Zs schizophrenic? That’s probably the wrong term, but I think I am heading in the right direction. Mental disorder signals flashing. Just the Gen Z I want to avoid if possible.

One aspect of the write up in the article is that the “author” — maybe human, maybe AI, maybe Gen X with a grudge, who knows? — is that some explanation of who paid the bill to obtain data from 2,000 people. Okay, who paid the bill? Answer: Lenovo. What company conducted the study? Answer: OnePoll. (I never heard of the outfit, and I am too much of a dinobaby to care much.)

Net net: The Gen Zs seem to be a prime source of persons of interest for those investigating certain types of online crime. There you go.

Stephen E Arnold, June 6, 2024

Which Came First? Cliffs Notes or Info Short Cuts

May 8, 2024

This essay is the work of a dinobaby. Unlike some folks, no smart software improved my native ineptness.

This essay is the work of a dinobaby. Unlike some folks, no smart software improved my native ineptness.

The first online index I learned about was the Stanford Research Institute’s Online System. I think I was a sophomore in college working on a project for Dr. William Gillis. He wanted me to figure out how to index poems for a grant he had. The SRI system opened my eyes to what online indexes could do.

Later I learned that SRI was taking ideas from people like Valerius Maximus (30 CE) and letting a big, expensive, mostly hot group of machines do what a scribe would do in a room filled with rolled up papyri. My hunch is that other workers in similar “documents” figures out that some type of labeling and grouping system made sense. Sure, anyone could grab a roll, untie the string keeping it together, and check out its contents. “Hey,” someone said, “Put a label on it and make a list of the labels. Alphabetize the list while you are at it.”

An old-fashioned teacher struggles to get students to produce acceptable work. She cannot write TL;DR. The parents will find their scrolling adepts above such criticism. Thanks, MSFT Copilot. How’s the security work coming?

I thought about the common sense approach to keeping track of and finding information when I read “The Defensive Arrogance of TL;DR.” The essay or probably more accurately the polemic calls attention to the précis, abstract, or summary often included with a long online essay. The inclusion of what is now dubbed TL;DR is presented as meaning, “I did not read this long document. I think it is about this subject.”

On one hand, I agree with this statement:

We’re at a rolling boil, and there’s a lot of pressure to turn our work and the work we consume to steam. The steam analogy is worthwhile: a thirsty person can’t subsist on steam. And while there’s a lot of it, you’re unlikely to collect enough as a creator to produce much value.

The idea is that content is often hot air. The essay includes a chart called “The Rise of Dopamine Culture, created by Ted Gioia. Notice that the world of Valerius Maximus is not in the chart. The graphic begins with “slow traditional culture” and zips forward to the razz-ma-tazz datasphere in which we try to survive.

I would suggest that the march from bits of grass, animal skins, clay tablets, and pieces of tree bark to such examples of “slow traditional culture” like film and TV, albums, and newspapers ignores the following:

- Indexing and summarizing remained unchanged for centuries until the SRI demonstration

- In the last 61 years, manual access to content has been pushed aside by machine-centric methods

- Human inputs are less useful

As a result, the TL;DR tells us a number of important things:

- The person using the tag and the “bullets” referenced in the essay reveal that the perceived quality of the document is low or poor. I think of this TL;DR as a reverse Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval. We have a user assigned “Seal of Disapproval.” That’s useful.

- The tag makes it possible to either NOT out the content with a TL;DR tag or group documents by the author so tagged for review. It is possible an error has been made or the document is an aberration which provides useful information about the author.

- The person using the tag TL;DR creates a set of content which can be either processed by smart software or a human to learn about the tagger. An index term is a useful data point when creating a profile.

I think the speed with which electronic content has ripped through culture has caused a number of jarring effects. I won’t go into them in this brief post. Part of the “information problem” is that the old-fashioned processes of finding, reading, and writing about something took a long time. Now Amazon presents machine-generated books whipped up in a day or two, maybe less.

TL;DR may have more utility in today’s digital environment.

Stephen E Arnold, May 8, 2024

Social Scoring Is a Thing and in Use in the US and EU Now

April 9, 2024

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

Social scoring is a thing.

The EU AI regulations are not too keen on slapping an acceptability number on people or a social score. That’s a quaint idea because the mechanisms for doing exactly that are available. Furthermore, these are not controlled by the EU, and they are not constrained in a meaningful way in the US. The availability of mechanisms for scoring a person’s behaviors chug along within the zippy world of marketing. For those who pay attention to policeware and intelware, many of the mechanisms are implemented in specialized software.

Will the two match up? Thanks, MSFT Copilot. Good enough.

There’s a good rundown of the social scoring tools in “The Role of Sentiment Analysis in Marketing.” The content is focused on uses “emotional” and behavioral signals to sell stuff. However, the software and data sets yield high value information for other purposes. For example, an individual with access to data about the video viewing and Web site browsing about a person or a cluster of persons can make some interesting observations about that person or group.

Let me highlight some of the software mentioned in the write up. There is an explanation of the discipline of “sentiment analysis.” A person engaged in business intelligence, investigations, or planning a disinformation campaign will have to mentally transcode the lingo into a more practical vocabulary, but that’s no big deal. The write up then explains how “sentiment analysis” makes it possible to push a person’s buttons. The information makes clear that a service with a TikTok-type recommendation system or feed of “you will probably like this” can exert control over an individual’s ideas, behavior, and perception of what’s true or false.

The guts of the write up is a series of brief profiles of eight applications available to a marketer, PR team, or intelligence agency’s software developers. The products described are:

- Sprout Social. Yep, it’s wonderful. The company wrote the essay I am writing about.

- Reputation. Hello, social scoring for “trust” or “influence”

- Monkeylearn. What’s the sentiment of content? Monkeylearn can tell you.

- Lexalytics. This is an old-timer in sentiment analysis.

- Talkwalker. A content scraper with analysis and filter tools. The company is not “into” over-the-transom inquiries

If you have been thinking about the EU’s AI regulations, you might formulate an idea that existing software may irritate some regulators. My team and I think that AI regulations may bump into companies and government groups already using these tools. Working out the regulatory interactions between AI regulations and what has been a reasonably robust software and data niche will be interesting.

In the meantime, ask yourself, “How many intelware and policeware systems implement either these tools or similar tools?” In my AI presentation at the April 2024 US National Cyber Crime Conference, I will provide a glimpse of the future by describing a European company which includes some of these functions. Regulations do not control technology nor innovation.

Stephen E Arnold, April 9, 2024

In Big Data, Bad Data Does Not Matter. Not So Fast, Mr. Slick

April 8, 2024

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

When I hear “With big data, bad data does not matter. It’s the law of big numbers. Relax,” I chuckle. Most data present challenges. First, figuring out which data are accurate can be a challenge. But the notion of “relax,” does not cheer me. Then one can consider data which have been screwed up by a bad actor, a careless graduate student, a low-rent research outfit, or someone who thinks errors are not possible.

The young vendor is confident that his tomatoes and bananas are top quality. The color of the fruit means nothing. Thanks, MSFT Copilot. Good enough, like the spoiled bananas.

“Data Quality Getting Worse, Report Says” offers some data (which may or may not be on the mark) which remind me to be skeptical of information available today. The Datanami article points out:

According to the company’s [DBT Labs’] State of Analytics Engineering 2024 report released yesterday, poor data quality was the number one concern of the 456 analytics engineers, data engineers, data analysts, and other data professionals who took the survey. The report shows that 57% of survey respondents rated data quality as one of the three most challenging aspects of the data preparation process. That’s a significant increase from the 2022 State of Analytics Engineering report, when 41% indicated poor data quality was one of the top three challenges.

The write up offers several other items of interest; for example:

- Questions about who owns the data

- Integration of fusion of multiple data sources

- Documenting data products; that is, the editorial policy of the producer / collector of the information.

This flashing yellow light about data seems to be getting brighter. The implication of the report is that data quality “appears” to be be heading downhill. The write up quotes Jignesh Patel, computer science professor at Carnegie Mellon University to underscore the issue:

“Data will never be fully clean. You’re always going to need some ETL [extract, transform, and load] portion. The reason that data quality will never be a “solved problem,” is partly because data will always be collected from various sources in various ways, and partly because or data quality lies in the eye of the beholder. You’re always collecting more and more data. If you can find a way to get more data, and no one says no to it, it’s always going to be messy. It’s always going to be dirty.”

But what about the assertion that in big data, bad data will be a minor problem. That assertion may be based on a lack of knowledge about some of the weak spots in data gathering processes. In the last six months, my team and I have encountered these issues:

- The source of the data contained a flaw so that it was impossible to determine what items were candidates for filtering out

- The aggregator had zero controls because it acquired data from another party and did not homework other than hyping a new data set

- Flawed data filled the exception folder with a large percentage of the information that remediation was not possible due to time and cost constraints

- Automated systems are indiscriminate, and few (sometimes no one) pay close attention to inputs.

I agree that data quality is a concern. However, efficiency trumps old-fashioned controls and checks applied via subject matter experts and trained specialists. The fix will be smart software which will be cheaper and more opaque. The assumption that big data will be self healing may not be accurate, but it sounds good.

Stephen E Arnold, April 8, 2024

How Smart Software Works: Well, No One Is Sure It Seems

March 21, 2024

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

The title of this Science Daily article strikes me a slightly misleading. I thought of my asking my son when he was 14, “Where did you go this afternoon?” He would reply, “Nowhere.” I then asked, “What did you do?” He would reply, “Nothing.” Helpful, right? Now consider this essay title:

How Do Neural Networks Learn? A Mathematical Formula Explains How They Detect Relevant Patterns

AI experts are unable to explain how smart software works. Thanks, MSFT Copilot Bing. You have smart software figured out, right? What about security? Oh, I am sorry I asked.

Ah, a single formula explains pattern detection. That’s what the Science Daily title says I think.

But what does the write up about a research project at the University of San Diego say? Something slightly different I would suggest.

Consider this statements from the cited article:

“Technology has outpaced theory by a huge amount.” — Mikhail Belkin, the paper’s corresponding author and a professor at the UC San Diego Halicioglu Data Science Institute

What’s the consequence? Consider this statement:

“If you don’t understand how neural networks learn, it’s very hard to establish whether neural networks produce reliable, accurate, and appropriate responses.

How do these black box systems work? Is this the mathematical formula? Average Gradient Outer Product or AGOP. But here’s the kicker. The write up says:

The team also showed that the statistical formula they used to understand how neural networks learn, known as Average Gradient Outer Product (AGOP), could be applied to improve performance and efficiency in other types of machine learning architectures that do not include neural networks.

Net net: Coulda, woulda, shoulda does not equal understanding. Pattern detection does not answer the question of what’s happening in black box smart software. Try again, please.

Stephen E Arnold, March 21, 2024

Synthetic Data: From Science Fiction to Functional Circumscription

March 4, 2024

This essay is the work of a dumb humanoid. No smart software required.

This essay is the work of a dumb humanoid. No smart software required.

Synthetic data are information produced by algorithms, not by real-world events. It’s created using real-world data and numerical recipes. The appeal is that it is easier than collecting real life information, cheaper than dealing with data from real life, and faster than fooling around with surveys, monitoring devices, and law suits. In theory, synthetic data is one promising way of skirting the expense of getting humans involved.

“What Is [a] Synthetic Sample – And Is It All It’s Cracked Up to Be?” tackles the subject of a synthetic sample, a topic which is one slice of the synthetic data universe. The article seeks “to uncover the truth behind artificially created qualitative and quantitative market research data.” I am going to avoid the question, “Is synthetic data useful?” because the answer is, “Yes.” Bean counters and those looking to find a way out of the pickle barrel filled with expensive brine are going to chase after the magic of algorithms producing data to do some machine learning magic.

In certain situations, fake flowers are super. Other times, the faux blooms are just creepy. Thanks, MSFT Copilot Bing thing. Good enough.

Are synthetic data better than real world data? The answer from my vantage point is, “It depends.” Fancy math can prove that for some use cases, synthetic data are “good enough”; that is, the data produce results close enough to what a “real” data set provides. Therefore, just use synthetic data. But for other applications, synthetic data might throw some sand in the well-oiled marketing collateral describing the wonders of synthetic data. (Some university research labs are quite skilled in PR speak, but the reality of their methods may not line up with the PowerPoints used to raise venture capital.)

This essay discusses a research project to figure out if a synthetic sample works or in my lingo if the synthetic sample is good enough. The idea is that as long as the synthetic data is within a specified error range, the synthetic sample can be used and may produce “reliable” or useful results. (At least one hopes this is the case.)

I want to focus on one portion of the cited article and invite you to read the complete Kantar explanation.

Here’s the passage which snagged my attention:

… right now, synthetic sample currently has biases, lacks variation and nuance in both qual and quant analysis. On its own, as it stands, it’s just not good enough to use as a supplement for human sample. And there are other issues to consider. For instance, it matters what subject is being discussed. General political orientation could be easy for a large language model (LLM), but the trial of a new product is hard. And fundamentally, it will always be sensitive to its training data – something entirely new that is not part of its training will be off-limits. And the nature of questioning matters – a highly ’specific’ question that might require proprietary data or modelling (e.g., volume or revenue for a particular product in response to a price change) might elicit a poor-quality response, while a response to a general attitude or broad trend might be more acceptable.

These sentences present several thorny problems is academic speak. Let’s look at them in the vernacular of rural Kentucky where I live.

First, we have the issue of bias. Training data can be unintentionally or intentionally biased. Sample radical trucker posts on Telegram, and use those messages to train a model like Reor. That output is going to express views that some people might find unpalatable. Therefore, building a synthetic data recipe which includes this type of Telegram content is going to be oriented toward truck driver views. That’s good and bad.

Second, a synthetic sample may require mixing data from a “real” sample. That’s a common sense approach which reduces some costs. But will the outputs be good enough. The question then becomes, “Good enough for what applications?” Big, general questions about how a topic is presented might be close enough for horseshoes. Other topics like those focusing on dealing with a specific technical issue might warrant more caution or outright avoidance of synthetic data. Do you want your child or wife to die because the synthetic data about a treatment regimen was close enough for horseshoes. But in today’s medical structure, that may be what the future holds.

Third, many years ago, one of the early “smart” software companies was Autonomy, founded by Mike Lynch. In the 1990s, Bayesian methods were known but some — believe it or not — were classified and, thus, not widely known. Autonomy packed up some smart software in the Autonomy black box. Users of this system learned that the smart software had to be retrained because new terms and novel ideas not in the original training set were not findable by the neuro linguistic program’s engine. Yikes, retraining requires human content curation of data sets, time to retrain the system, and the expense of redeploying the brains of the black boxes. Clients did not like this and some, to be frank, did not understand why a product did not work like an MG sports car. Synthetic data has to be trained to “know” about new terms and avid the “certain blindness” probability based systems possess.

Fourth, the topic of “proprietary data modeling” means big bucks. The idea behind synthetic data is that it is cheaper. Building proprietary training data and keeping it current is expensive. Is it better? Yeah, maybe. Is it faster? Probably not when humans are doing the curation, cleaning, verifying, and training.

The write up states:

But it’s likely that blended models (human supplemented by synthetic sample) will become more common as LLMs get even more powerful – especially as models are finetuned on proprietary datasets.

Net net: Synthetic data warrants monitoring. Some may want to invest in synthetic data set companies like Kantar, for instance. I am a dinobaby, and I like the old-fashioned Stone Age approach to data. The fancy math embodies sufficient risk for me. Why increase risk? Remember my reference to a dead loved one? That type of risk.

Stephen E Arnold, March 4, 2023

Bad News Delivered via Math

March 1, 2024

This essay is the work of a dumb humanoid. No smart software required.

This essay is the work of a dumb humanoid. No smart software required.

I am not going to kid myself. Few people will read “Hallucination is Inevitable: An Innate Limitation of Large Language Models” with their morning donut and cold brew coffee. Even fewer will believe what the three amigos of smart software at the National University of Singapore explain in their ArXiv paper. Hard on the heels of Sam AI-Man’s ChatGPT mastering Spanglish, the financial payoffs are just too massive to pay much attention to wonky outputs from smart software. Hey, use these methods in Excel and exclaim, “This works really great.” I would suggest that the AI buggy drivers slow the Kremser down.

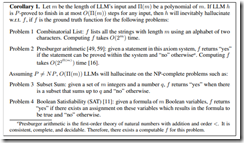

The killer corollary. Source: Hallucination is Inevitable: An Innate Limitation of Large Language Models.

The paper explains that large language models will be reliably incorrect. The paper includes some fancy and not so fancy math to make this assertion clear. Here’s what the authors present as their plain English explanation. (Hold on. I will give the dinobaby translation in a moment.)

Hallucination has been widely recognized to be a significant drawback for large language models (LLMs). There have been many works that attempt to reduce the extent of hallucination. These efforts have mostly been empirical so far, which cannot answer the fundamental question whether it can be completely eliminated. In this paper, we formalize the problem and show that it is impossible to eliminate hallucination in LLMs. Specifically, we define a formal world where hallucination is defined as inconsistencies between a computable LLM and a computable ground truth function. By employing results from learning theory, we show that LLMs cannot learn all of the computable functions and will therefore always hallucinate. Since the formal world is a part of the real world which is much more complicated, hallucinations are also inevitable for real world LLMs. Furthermore, for real world LLMs constrained by provable time complexity, we describe the hallucination-prone tasks and empirically validate our claims. Finally, using the formal world framework, we discuss the possible mechanisms and efficacies of existing hallucination mitigators as well as the practical implications on the safe deployment of LLMs.

Here’s my take:

- The map is not the territory. LLMs are a map. The territory is the human utterances. One is small and striving. The territory is what is.

- Fixing the problem requires some as yet worked out fancier math. When will that happen? Probably never because of no set can contain itself as an element.

- “Good enough” may indeed by acceptable for some applications, just not “all” applications. Because “all” is a slippery fish when it comes to models and training data. Are you really sure you have accounted for all errors, variables, and data? Yes is easy to say; it is probably tough to deliver.

Net net: The bad news is that smart software is now the next big thing. Math is not of too much interest, which is a bit of a problem in my opinion.

Stephen E Arnold, March 1, 2024

Surprise! Smart Software and Medical Outputs May Kill You

February 29, 2024

This essay is the work of a dumb humanoid. No smart software required.

This essay is the work of a dumb humanoid. No smart software required.

Have you been inhaling AI hype today? Exhale slowly, then read “Generating Medical Errors: GenAI and Erroneous Medical References,” produced by the esteemed university with a reputation for shaking the AI cucarachas and singing loudly “Ai, Ai, Yi.” The write up is an output of the non-plagiarizing professionals in the Human Centered Artificial Intelligence unit.

The researchers report states:

…Large language models used widely for medical assessments cannot back up claims.

Here’s what the HAI blog post states:

we develop an approach to verify how well LLMs are able to cite medical references and whether these references actually support the claims generated by the models. The short answer: poorly. For the most advanced model (GPT-4 with retrieval augmented generation), 30% of individual statements are unsupported and nearly half of its responses are not fully supported.

Okay, poorly. The disconnect is that the output sounds good, but the information is distorted, off base, or possibly inappropriate.

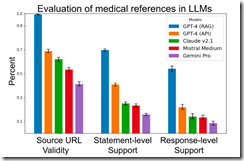

What I found interesting is a stack ranking of widely used AI “systems.” Here’s the chart from the HAI article:

The least “poor” are the Sam AI-Man systems. In the middle is the Anthropic outfit. Bringing up the rear is the French “small” LLM Mistral system. And guess which system is dead last in this Stanford report?

Give up?

The Google. And not just the Google. The laggard is the Gemini system which was Bard, a smart software which rolled out after the Softies caught the Google by surprise about 14 months ago. Last in URL validity, last in statement level support, and last in response level support.

The good news is that most research studies are non reproducible or, like the former president of Stanford’s work, fabricated. As a result, I think these assertions will be easy for an art history major working in Google’s PR confection machine will bat them away like annoying flies in Canberra, Australia.

But last from researchers at the estimable institution where Google, Snorkel and other wonderful services were invented? That’s a surprise like the medical information which might have unexpected consequences for Aunt Mille or Uncle Fred.

Stephen E Arnold, February 29, 2024