Open Source Versus Commercial Software. The Result? A Hybrid Which Neither Parent May Love

September 30, 2024

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

I have been down the open source trail a couple of times. The journey was pretty crazy because open source was software created to fulfill a computer science class requirement, a way to provide some “here’s what I can do” vibes to a résumé when résumés were anchored to someone’s reality, and “play” that would get code adopted so those in the know could sell services like engineering support, customizing, optimizing, and “making it mostly work.” In this fruit cake, were licenses, VCs, lone-wolves, and a few people creating something useful for a “community” which might or might not “support” the effort. Flip enough open source rocks and one finds some fascinating beasts like IBM, Microsoft, and other giant technology outfits.

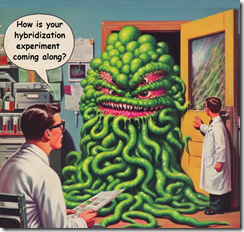

Some hybrids work; others do not. Thanks, MSFT Copilot, good enough.

Today I learned their is now a hybrid of open source and proprietary (commercial) software. According to the “Some Startups Are Going Fair Source to Avoid the Pitfalls of Open Source Licensing” states:

The fair source concept is designed to help companies align themselves with the “open” software development sphere, without encroaching into existing licensing landscapes, be that open source, open core, or source-available, and while avoiding any negative associations that exist with “proprietary.” However, fair source is also a response to the growing sense that open source isn’t working out commercially.

Okay. I think “not working out commercially” is “real news” speak for “You can’t make enough money to become a Silicon Type mogul.” The write up adds:

Businesses that have flown the open source flag have mostly retreated to protect their hard work, moving either from fully permissive to a more restrictive “copyleft” license, as the likes of Element did last year and Grafana before it, or ditched open source altogether as HashiCorp did with Terraform.

These are significant developments. What about companies which have built substantial businesses surfing on open source software and have not been giving back in equal measure to the “community”? My hunch is that many start ups use the open source card as a way to get some marketing wind in their tiny sails. Other outfits just cobble together a number of open source software components and assemble a new and revolutionary product. The savings come from the expense of developing an original solution and using open source software to build what becomes a proprietary system. The origins of some software is either ignored by some firms or lost in the haze of employee turnover. After all, who remembers? A number of intelware companies which off specialized services to government agencies incorporate some open source software and use their low profile or operational secrecy to mask what their often expensive products provide to a government entity.

The write up notes:

For now, the main recommended fair source license is the Functional Source License (FSL), which Sentry itself launched last year as a simpler alternative to BUSL. However, BUSL itself has also now been designated fair source, as has another new Sentry-created license called the Fair Core License (FCL), both of which are included to support the needs of different projects. Companies are welcome to submit their own license for consideration, though all fair source licenses should have three core stipulations: It [the code] should be publicly available to read; allow third parties to use, modify, and redistribute with “minimal restrictions“; and have a delayed open source publication (DOSP) stipulation, meaning it converts to a true open source license after a predefined period of time. With Sentry’s FSL license, that period is two years; for BUSL, the default period is four years. The concept of “delaying” publication of source code under a true open source license is a key defining element of a fair source license, separating it from other models such as open core. The DOSP protects a company’s commercial interests in the short term, before the code becomes fully open source.

My reaction is that lawyers will delight in litigating such notions as “minimal restrictions.” The cited article correctly in my opinion says:

Much is open to interpretation and can be “legally fuzzy.”

Is a revolution in software licensing underway?

Some hybrids live; others die.

Stephen E Arnold, September 30, 2024