KPMG FOMO on AI

December 11, 2024

This blog post flowed from the sluggish and infertile mind of a real live dinobaby. If there is art, smart software of some type was probably involved.

This blog post flowed from the sluggish and infertile mind of a real live dinobaby. If there is art, smart software of some type was probably involved.

AI is in demand and KPMG long ago received the message that it needs to update its services to include AI consulting services in its offerings. Technology Magazine shares the story in: “Growing KPMG-Google Cloud Ties Signal AI Services Shift.” Google Cloud and KPMG have a partnership that started when the latter’s clients wanted to implement Google Cloud into their systems. KPMG’s client base increased tenfold when they deployed Google Cloud services.

The nature of the partnership will change to Google’s AI-related services and KPMG budgeted $100 million to the project. The investment is projected to give KPMG $1 billion in revenue for its generative AI technology. KPMG deployed Google’s enterprise search technology Vertex AI Search into its cloud services. Vertex AI and retrieval augmented generation (RAG), a process that checks AI responses with verified data, are being designed to analyze and assist with market and research analysis.

The partnership between these tech companies indicates this is where the tech industry is going:

“The partnership indicates how professional services firms are evolving their technology practices. KPMG’s approach combines its industry expertise with Google Cloud’s technical infrastructure, creating services that bridge the gap between advanced technology and practical business applications… The collaboration also reflects how enterprise AI adoption is maturing. Rather than implementing generic AI solutions, firms are now seeking industry-specific applications that integrate with existing systems and workflows. This approach requires deep understanding of both technical capabilities and sector-specific challenges.”

Need an accounting firm? Well, AI is accounting. Need a consultant. Well, AI is consulting. Need motivated people to bill your firm by the hour at exorbitant fees? You know whom to call.

Whitney Grace, December 11, 2024

AI Automation: Spreading Like Covid and Masks Will Not Help

December 10, 2024

This blog post flowed from the sluggish and infertile mind of a real live dinobaby. If there is art, smart software of some type was probably involved.

This blog post flowed from the sluggish and infertile mind of a real live dinobaby. If there is art, smart software of some type was probably involved.

Reddit is the one of the last places on the Internet where you can find quality and useful information. Reddit serves as the Internet’s hub for news, tech support, trolls, and real-life perspectives about jobs. Here’s a Reddit downer in the ChatGPT thread for anyone who works in a field that can be automated: “Well this is it boys. I was just informed from my boss and HR that my entire profession is being automated away.”

For brevity’s sake here is the post:

“For context I work production in local news. Recently there’s been developments in AI driven systems that can do 100% of the production side of things which is, direct, audio operate, and graphic operate -all of those jobs are all now gone in one swoop. This has apparently been developed by the company Q ai. For the last decade I’ve worked in local news and have garnered skills I thought I would be able to take with me until my retirement, now at almost 30 years old, all of those job opportunities for me are gone in an instant. The only person that’s keeping their job is my manager, who will overlook the system and do maintenance if needed. That’s 20 jobs lost and 0 gained for our station. We were informed we are going to be the first station to implement this under our company. This means that as of now our entire production staff in our news station is being let go. Once the system is implemented and running smoothly then this system is going to be implemented nationwide (effectively eliminating tens of thousands of jobs.) There are going to be 0 new jobs built off of this AI platform. There are people I work with in their 50’s, single, no college education, no family, and no other place to land a job once this kicks in. I have no idea what’s going to happen to them. This is it guys. This is what our future with AI looks like. This isn’t creating any new jobs this is knocking out entire industry level jobs without replacing them.”

The post is followed by comments of commiseration, encouragement, and the usual doom and gloom. It’s not surprising that local news stations are automating their tasks, especially with the overhead associates with employees. These include: healthcare, retirement package, vacation days, PTO, and more. AI is the perfect employee, because it doesn’t complain or take time off. AI, however, is lacking basic common sense and fact checking. We’re witnessing a change in how the job market, it just sucks to live through it.

Whitney Grace, December 10, 2024

Amazon: Black FridAI for Smart Software Arrives

December 9, 2024

This write up was created by an actual 80-year-old dinobaby. If there is art, assume that smart software was involved. Just a tip.

This write up was created by an actual 80-year-old dinobaby. If there is art, assume that smart software was involved. Just a tip.

Five years ago, give or take a year, my team and I were giving talks about Amazon. Our topics touched on Amazon’s blockchain patents, particularly some interesting cross blockchain filings, and Amazon’s idea for “off the shelf” smart software. At the time, we compared the blockchain patents to examining where data resided across different public ledgers. We also showed pictures of Lego blocks. The idea was that a customer of Amazon Web Service could select a data package, a model, and some other Amazon technologies and create amazing AWS-infused online confections.

Thanks, MidJourney. Good enough.

Well, as it turned out the ideas were interesting, but Amazon just did not have the crate engine stuffed in its digital flea market to make the ideas go fast. The fix has been Amazon’s injections of cash and leadership attention into Anthropic and a sweeping concept of partnering with other AI outfits. (Hopefully one of these ideas will make Amazon’s Alexa into more than a kitchen timer. Well, we’ll see.)

I read “First Impressions of the New Amazon Nova LLMs (Via a New LLM-Bedrock Plugin).” I am going to skip the Amazon jargon and focus on one key point in the rah rah write up:

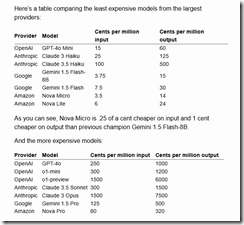

This is a nicely presented pricing table. You can work through the numbers and figure out how much Amazon will “save” some AI-crazed customer. I want to point out that Amazon is bringing price cutting to the world of smart software. Every day will be a Black FridAI for smart software.

That’s right. Amazon is cutting prices for AI, and that is going to set the stage for a type of competitive joust most of the existing AI players were not expecting to confront. Sure, there are “free” open source models, but you have to run them somewhere. Amazon wants to be that “where”.

If Amazon pulls off this price cutting tactic, some customers will give the system a test drive. Amazon offers a wide range of ways to put one’s toes in the smart software swimming pool. There are training classes; there will be presentations at assorted Amazon events; and there will be a slick way to make Amazon’s smart software marketing make money. Not too many outfits can boost advertising prices and Prime membership fees as part of the smart software campaign.

If one looks at Amazon’s game plan over the last quarter century, the consequences are easy to spot: No real competition for digital books or for semi affluent demographics desire to have Amazon trucks arrive multiple times a day. There is essentially no quality or honesty controls on some of the “partners” in the Amazon ecosystem. And, I personally received a pair of large red women’s underpants instead of an AMD Ryzen CPU. I never got the CPU, but Amazon did not allow me to return the unused thong. Charming.

Now it is possible that this cluster of retail tactics will be coming to smart software. Am I correct, or am I just reading into the play book which has made Amazon a fave among so many vendors of so many darned products?

Worth watching because price matters.

Stephen E Arnold, December 9, 2024

Smart Software Is Coming for You. Yes, You!

December 9, 2024

This write up was created by an actual 80-year-old dinobaby. If there is art, assume that smart software was involved. Just a tip.

This write up was created by an actual 80-year-old dinobaby. If there is art, assume that smart software was involved. Just a tip.

“Those smart software companies are not going to be able to create a bot to do what I do.” — A CPA who is awash with clients and money.

Now that is a practical, me–me-me idea. However, the estimable Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD, a delightful acronym) has data suggesting a slightly different point of view: Robots will replace workers who believe themselves unreplaceable. (The same idea is often held by head coaches of sports teams losing games.)

Thanks, MidJourney. Good enough.

The report is titled in best organizational group think: Job Creation and Local Economic Development 2024; The Geography of Generative AI.

I noted this statement in the beefy document, presumably written by real, live humanoids and not a ChatGPT type system:

In fact, the finance and insurance industry is the tightest industry in the United States, with 2.5 times more vacancies per filled position than the regional average (1.6 times in the European Union).

I think this means that financial institutions will be eager to implement smart software to become “workers.” If that works, the confident CPA quoted at the beginning of this blog post is going to get a pink slip.

The OECD report believes that AI will have a broad impact. The most interesting assertion / finding in the report is that one-fifth of the tasks a worker handles can be handled by smart software. This figure is interesting because smart software hallucinates and is carrying the hopes and dreams of many venture outfits and forward leaning wizards on its digital shoulders.

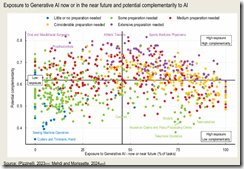

And what’s a bureaucratic report without an almost incomprehensible chart like this one from page 145 of the report?

Look closely and you will see that sewing machine operators are more likely to retain jobs than insurance clerks.

Like many government reports, the document focuses on the benefits of smart software. These include (cue the theme from Star Wars, please) more efficient operations, employees who do more work and theoretically less looking for side gigs, and creating ways for an organization to get work done without old-school humans.

Several observations:

- Let’s assume smart software is almost good enough, errors and all. The report makes it clear that it will be grabbed and used for a plethora of reasons. The main one is money. This is an economic development framework for the research.

- The future is difficult to predict. After scanning the document, I was thinking that a couple of college interns and an account to You.com would be able to generate a reasonable facsimile of this report.

- Agents can gather survey data. One hopes this use case takes hold in some quasi government entities. I won’t trot out my frequently stated concerns about “survey” centric reports.

Stephen E Arnold, December 9, 2024

Grousing about Smart Software: Yeah, That Will Work

December 6, 2024

This is the work of a dinobaby. Smart software helps me with art, but the actual writing? Just me and my keyboard.

This is the work of a dinobaby. Smart software helps me with art, but the actual writing? Just me and my keyboard.

I read “Writers Condemn Startup’s Plans to Publish 8,000 Books Next Year Using AI.” The innovator is an outfit called Spines. Cute, book spines and not mixed up with spiny mice or spiny rats.

The write up reports:

Spines – which secured $16m in a recent funding round – says that authors will retain 100% of their royalties. Co-founder Yehuda Niv, who previously ran a publisher and publishing services business in Israel, claimed that the company “isn’t self-publishing” or a vanity publisher but a “publishing platform”.

A platform, not a publisher. The difference is important because venture types don’t pump cash into traditional publishing companies in my experience.

The article identified another key differentiator for Spines:

Spines says it will reduce the time it takes to publish a book to two to three weeks.

When publishers with whom I worked talked about time, the units were months. In one case, it was more than a year. When I was writing books, the subject matter changed on a slightly different time scale. Traditional publishers do not zip along with the snappiness of a two year old French bulldog.

Spines is quoted in the write up as saying:

[We are] levelling the playing field for any person who aspires to be an author to get published within less than three weeks and at a fraction of the cost. Our goal is to help one million authors to publish their books using technology….”

Yep, technology. Is that a core competency of big time publishers?

Several observations from my dinobaby-friendly lair:

- If Spines works — that is, makes lots of money — a traditional publisher will probably buy the company and sue any entity which impinges on its “original” ideas.

- Costs for instant publishing on Amazon remain more attractive. The fees are based on delivery of digital content and royalties assessed. Spines may have to spend money to find writers able to pay the company to do the cover, set up, design, etc.

- Connecting agentic AI into a Spines-type service may be interesting to some.

Stephen E Arnold, December 6, 2024

Batting Google and Whiffing the Chance

December 6, 2024

This is the work of a dinobaby. Smart software helps me with art, but the actual writing? Just me and my keyboard.

This is the work of a dinobaby. Smart software helps me with art, but the actual writing? Just me and my keyboard.

I read “The AI War Was Never Just about AI.” Okay, AI war. We have a handful of mostly unregulated technology companies, a few nation states, and some unknown wizards working in their family garage. The situation is that a very tiny number of companies are fighting to become de facto reality definers for the next few years, maybe a decade or two. Against that background, does a single country’s judiciary think it can “regulate” an online company. One pragmatic approach has been to ban a service, the approach taken by Australia, China, Iran, and Russia among others. A less popular approach would be to force the organization out of business by arresting key executives, seizing assets, and imposing penalties on that organization’s partners. Does that sound a bit over the top?

The cited article does not go to the pit in the apricot. Google has been allowed to create an interlocking group of services which permeate the fabric of global online activity. There is no entertainment for some people in Armenia except YouTube. There are few choices to promote a product online without bumping into the Disney style people herders who push those who want to sell toward Google’s advertising systems. There is no getting from Point A to Point B without Google’s finding services whether dolled up in an AI wrapper, a digital version of a map, or a helpful message on the sign of a lawn service truck for Google Local.

The write up says:

The government wants to break up Google’s monopoly over the search market, but its proposed remedies may in fact do more to shape the future of AI. Google owns 15 products that serve at least half a billion people and businesses each—a sprawling ecosystem of gadgets, search and advertising, personal applications, and enterprise software. An AI assistant that shows up in (or works well with) those products will be the one that those people are most likely to use. And Google has already woven its flagship Gemini AI models into Search, Gmail, Maps, Android, Chrome, the Play Store, and YouTube, all of which have at least 2 billion users each. AI doesn’t have to be life-changing to be successful; it just has to be frictionless.

Okay. With a new administration taking the stage, how will this goal of leveling the playing field work. The legal processes at Google’s disposal mean that whatever the US government does can be appealed. Appeals take time. Who lasts longer? A government lawyer working under the thumb of DOGE and budget cutting or a giant outfit like Google? My view is that Google has more lawyers and more continuity.

Second, breaking up Google may face some headwinds from government entities quite dependent on its activities. The entire OSINT sector looks to Google for nuggets of information. It is possible some government agencies have embedded Google personnel on site. The “advertising” industry depends on distribution via the online stores of Apple and Google. Why is this important? The data brokers repackage the app data into data streams consumed by some government agencies and their contractors.

The write up says:

This is why it’s relevant that the DOJ’s proposed antitrust remedy takes aim at Google’s broader ecosystem. Federal and state attorneys asked the court to force Google to sell off its Chrome browser; cease preferencing its search products in the Android mobile operating system; prevent it from paying other companies, including Apple and Samsung, to make Google the default search engine; and allow rivals to syndicate Google’s search results and use its search index to build their own products. All of these and the DOJ’s other requests, under the auspices of search, are really shots at Google’s expansive empire.

So after more than 20 years of non regulation and hand slapping, the current legal decision is going to take apart an entity which is more like a cancer than a telephone company like AT&T. IBM was mostly untouched by the US government as was Microsoft. Now I am to to believe that a vastly different type of commercial enterprise which is for some functions more robust and effective than a government can have its wings clipped.

Is the Department of Justice concerned about AI? Come on. The DoJ personnel are thinking about the Department of Government Efficiency, presidential retribution, and enhancing LinkedIn profiles.

We are not in Kansas any longer where there is no AI war.

Stephen E Arnold, December 6, 2024

The Very Expensive AI Horse Race

December 4, 2024

This write up is from a real and still-alive dinobaby. If there is art, smart software has been involved. Dinobabies have many skills, but Gen Z art is not one of them.

This write up is from a real and still-alive dinobaby. If there is art, smart software has been involved. Dinobabies have many skills, but Gen Z art is not one of them.

One of the academic nemeses of smart software is a professional named Gary Marcus. Among his many intellectual accomplishments is cameo appearance on a former Jack Benny child star’s podcast. Mr. Marcus contributes his views of smart software to the person who, for a number of years, has been a voice actor on the Simpsons cartoon.

The big four robot stallions are racing to a finish line. Is the finish line moving away from the equines faster than the steeds can run? Thanks, MidJourney. Good enough.

I want to pay attention to Mr. Marcus’ Substack post “A New AI Scaling Law Shell Game?” The main idea is that the scaling law has entered popular computer jargon. Once the lingo of Galileo, scaling law now means that AI, like CPUs, are part of the belief that technology just gets better as it gets bigger.

In this essay, Mr. Marcus asserts that getting bigger may not work unless humanoids (presumably assisted by AI0 innovate other enabling processes. Mr. Marcus is aware of the cost of infrastructure, the cost of electricity, and the probable costs of exhausting content.

From my point of view, a bit more empirical “evidence” would be useful. (I am aware of academic research fraud.) Also, Mr. Marcus references me when he says keep your hands on your wallet. I am not sure that a fix is possible. The analogy is the old chestnut about changing a Sopwith Camel’s propeller when the aircraft is in a dogfight and the synchronized machine gun is firing through the propeller.

I want to highlight one passage in Mr. Marcus’ essay and offer a handful of comments. Here’s the passage I noted:

Over the last few weeks, much of the field has been quietly acknowledging that recent (not yet public) large-scale models aren’t as powerful as the putative laws were predicting. The new version is that there is not one scaling law, but three: scaling with how long you train a model (which isn’t really holding anymore), scaling with how long you post-train a model, and scaling with how long you let a given model wrestle with a given problem (or what Satya Nadella called scaling with “inference time compute”).

I think this is a paragraph I will add to my quotes file. The reasons are:

First, investors, would be entrepreneurs, and giant outfits really want a next big thing. Microsoft fired the opening shot in the smart software war in early 2023. Mr. Nadella suggested that smart software would be the next big thing for Microsoft. The company has invested in making good on this statement. Now Microsoft 365 is infused with smart software and Azure is burbling with digital glee with its “we’re first” status. However, a number of people have asked, “Where’s the financial payoff?” The answer is standard Silicon Valley catechism: The payoff is going to be huge. Invest now.” If prayers could power hope, AI is going to be hyperbolic just like the marketing collateral for AI promises. But it is almost 2025, and those billions have not generated more billions and profit for the Big Dogs of AI. Just sayin’.

Second, the idea that the scaling law is really multiple scaling laws is interesting. But if one scaling law fails to deliver, what happens to the other scaling laws? The interdependencies of the processes for the scaling laws might evoke new, hitherto identified scaling laws. Will each scaling law require massive investments to deliver? Is it feasible to pay off the investments in these processes with the original concept of the scaling law as applied to AI. I wonder if a reverse Ponzi scheme is emerging. The more pumped in the smaller the likelihood of success. Is AI a demonstration of convergence or The mathematical property you’re describing involves creating a sequence of fractions where the numerator is 1 and the denominator is an increasing sequence of integers. Just askin’.

Third, the performance or knowledge payoff I have experienced with my tests of OpenAI and the software available to me on You.com makes clear that the systems cannot handle what I consider routine questions. A recent example was my request to receive a list of the exhibitors at the November 1 Gateway Conference held in Dubai for crypto fans of Telegram’s The Open Network Foundation and TON Social. The systems were unable to deliver the lists. This is just one notable failure which a humanoid on my research team was able to rectify in an expeditious manner. (Did you know the Ku Group was on my researcher’s list?) Just reportin’.

Net net: Will AI repay the billions sunk into the data centers, the legal fees (many still looming), the staff, and the marketing? If you ask an accelerationist, the answer is, “Absolutely.” If you ask a dinobaby, you may hear, “Maybe, but some fundamental innovations are going to be needed.” If you ask an AI will kill us all type like the Xoogler Mo Gawdat, you will hear, “Doom looms.” Just dinobabyin’.

Stephen E Arnold, December 4, 2024

The New Coca Cola of Marketing: Xmas Ads

December 4, 2024

Though Coca-Cola has long purported that “It’s the Real Thing,” a recent ad is all fake. NBC News reports, “Coca-Cola Causes Controversy with AI-Made Ad.” We learn:

“Coca-Cola is facing backlash online over an artificial intelligence-made Christmas promotional video that users are calling ‘soulless’ and ‘devoid of any actual creativity.’ The AI-made video features everything from big red Coca-Cola trucks driving through snowy streets to people smiling in scarves and knitted hats holding Coca-Cola bottles. The video was meant to pay homage to the company’s 1995 commercial ‘Holidays Are Coming,’ which featured similar imagery, but with human actors and real trucks.”

The company’s last ad generated with AI, released earlier this year, did not face similar backlash. Is that because, as University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Neeraj Arora suggests, Coke’s Christmas ads are somehow sacrosanct? Or is it because March’s Masterpiece is actually original, clever, and well executed? Or because the artworks copied in that ad are treated with respect and, for some, clearly labeled? Whatever the reason, the riff on Coca-Cola’s own classic 1995 ad missed the mark.

Perhaps it was just too soon. It may be a matter of when, not if, the public comes to accept AI-generated advertising as the norm. One thing is certain: Coca Cola knows how to make sure marketing professors teach memorable case examples of corporate “let’s get hip” thinking.

Cynthia Murrell, December 4, 2024

New Concept: AI High

December 3, 2024

Is the AI hype-a-thon finally slowing? Nope. And our last nerves may not be the only thing to suffer. The AI industry could be shooting itself in the foot. ComputerWorld predicts, “AI Is on a Fast Track, but Hype and Immaturity Could Derail It.” Writer Scot Finnie reports:

“The hype is so extreme that a fall-out, which Gartner describes in its technology hype cycle reports as the ‘trough of disillusionment,’ seems inevitable and might be coming this year. That’s a testament to both genAI’s burgeoning potential and a sign of the technology’s immaturity. The outlook for deep learning for predictive models and genAI for communication and content generation is bright. But what’s been rarely mentioned amid the marketing blitz of recent months is that the challenges are also formidable. Machine learning tools are only as good as the data they’re trained with. Companies are finding that the millions of dollars they’ve spent on genAI have yielded lackluster ROI because their data is filled with contradictions, inaccuracies, and omissions. Plus, the hype surrounding the technology makes it difficult to see that many of the claimed benefits reside in the future, not the present.”

Oops. The article notes some of the persistent problems with generative AI, like hallucinations, repeated crashes ,and bias. Then there are the uses bad actors have for these tools, from phishing scams to deepfakes. For investors, disappointing results and returns are prompting second thoughts. None of this means AI is completely worthless, Finnie advises. He just suggests holding off until the rough edges are smoothed out before going all in. Probably a good idea. Digital mushrooms.

December 3, 2024

Deepfakes: An Interesting and Possibly Pernicious Arms Race

December 2, 2024

As it turns out, deepfakes are a difficult problem to contain. Who knew? As victims from celebrities to schoolchildren multiply exponentially, USA Today asks, “Can Legislation Combat the Surge of Non-Consensual Deepfake Porn?” Journalist Dana Taylor interviewed UCLA’s John Villasenor on the subject. To us, the answer is simple: Absolutely not. As with any technology, regulation is reactive while bad actors are proactive. Villasenor seems to agree. He states:

“It’s sort of an arms race, and the defense is always sort of a few steps behind the offense, right? In other words that you make a detection tool that, let’s say, is good at detecting today’s deepfakes, but then tomorrow somebody has a new deepfake creation technology that is even better and it can fool the current detection technology. And so then you update your detection technology so it can detect the new deepfake technology, but then the deepfake technology evolves again.”

Exactly. So if governments are powerless to stop this horror, what can? Perhaps big firms will fight tech with tech. The professor dreams:

“So I think the longer term solution would have to be automated technologies that are used and hopefully run by the people who run the servers where these are hosted. Because I think any reputable, for example, social media company would not want this kind of content on their own site. So they have it within their control to develop technologies that can detect and automatically filter some of this stuff out. And I think that would go a long way towards mitigating it.”

Sure. But what can be done while we wait on big tech to solve the problem it unleased? Individual responsibility, baby:

“I certainly think it’s good for everybody, and particularly young people these days to be just really aware of knowing how to use the internet responsibly and being careful about the kinds of images that they share on the internet. … Even images that are sort of maybe not crossing the line into being sort of specifically explicit but are close enough to it that it wouldn’t be as hard to modify being aware of that kind of thing as well.”

Great, thanks. Admitting he may sound naive, Villasenor also envisions education to the (partial) rescue:

“There’s some bad actors that are never going to stop being bad actors, but there’s some fraction of people who I think with some education would perhaps be less likely to engage in creating these sorts of… disseminating these sorts of videos.”

Our view is that digital tools allow the dark side of individuals to emerge and expand.

Cynthia Murrell, December 2, 2024