Taming AI Requires a Combo of AskJeeves and Watson Methods

April 15, 2024

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

I spotted a short item called “A Faster, Better Way to Prevent an AI Chatbot from Giving Toxic Responses.” The operative words from my point of view are “faster” and “better.” The write up reports (with a serious tone, of course):

Teams of human testers write prompts aimed at triggering unsafe or toxic text from the model being tested. These prompts are used to teach the chatbot to avoid such responses.

Yep, AskJeeves created rules. As long as the users of the system asked a question for which there was a rule, the helpful servant worked; for example, What’s the weather in San Francisco? However, ask a question for which there was no rule, what happens? The search engine reality falls behind the marketing juice and gets shopped until a less magical version appears as Ask.com. And then there is IBM Watson. That system endeared itself to groups of physicians who were invited to answer IBM “experts’” questions about cancer treatments. I heard when Watson was in full medical-revolution mode that some docs in a certain Manhattan hospital used dirty words to express his view about the Watson method. Rumor or actual factual? I don’t know, but involving humans in making software smart can be fraught with challenges: Managerial and financial to name but two.

The write up says:

Researchers from Improbable AI Lab at MIT and the MIT-IBM Watson AI Lab used machine learning to improve red-teaming. They developed a technique to train a red-team large language model to automatically generate diverse prompts that trigger a wider range of undesirable responses from the chatbot being tested. They do this by teaching the red-team model to be curious when it writes prompts, and to focus on novel prompts that evoke toxic responses from the target model. The technique outperformed human testers and other machine-learning approaches by generating more distinct prompts that elicited increasingly toxic responses. Not only does their method significantly improve the coverage of inputs being tested compared to other automated methods, but it can also draw out toxic responses from a chatbot that had safeguards built into it by human experts.

How much improvement? Does the training stick or does it demonstrate that charming “Bayesian drift” which allows the probabilities to go walk-about, nibble some magic mushrooms, and generate fantastical answers? How long did the process take? Was it iterative? So many questions, and so few answers.

But for this group of AI wizards, the future is curiosity-driven red-teaming. Presumably the smart software will not get lost, suffer heat stroke, and hallucinate. No toxicity, please.

Stephen E Arnold, April 15, 2024

Are Experts Misunderstanding Google Indexing?

April 12, 2024

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

Google is not perfect. More and more people are learning that the mystics of Mountain View are working hard every day to deliver revenue. In order to produce more money and profit, one must use Rust to become twice as wonderful than a programmer who labors to make C++ sit up, bark, and roll over. This dispersal of the cloud of unknowing obfuscating the magic of the Google can be helpful. What’s puzzling to me is that what Google does catches people by surprise. For example, consider the “real” news presented in “Google Books Is Indexing AI-Generated Garbage.” The main idea strikes me as:

But one unintended outcome of Google Books indexing AI-generated text is its possible future inclusion in Google Ngram viewer. Google Ngram viewer is a search tool that charts the frequencies of words or phrases over the years in published books scanned by Google dating back to 1500 and up to 2019, the most recent update to the Google Books corpora. Google said that none of the AI-generated books I flagged are currently informing Ngram viewer results.

Thanks, Microsoft Copilot. I enjoyed learning that security is a team activity. Good enough again.

Indexing lousy content has been the core function of Google’s Web search system for decades. Search engine optimization generates information almost guaranteed to drag down how higher-value content is handled. If the flagship provides the navigation system to other ships in the fleet, won’t those vessels crash into bridges?

In order to remediate Google’s approach to indexing requires several basic steps. (I have in various ways shared these ideas with the estimable Google over the years. Guess what? No one cared, understood, and if the Googler understood, did not want to increase overhead costs. So what are these steps? I shall share them:

- Establish an editorial policy for content. Yep, this means that a system and method or systems and methods are needed to determine what content gets indexed.

- Explain the editorial policy and what a person or entity must do to get content processed and indexed by the Google, YouTube, Gemini, or whatever the mystics in Mountain View conjure into existence

- Include metadata with each content object so one knows the index date, the content object creation date, and similar information

- Operate in a consistent, professional manner over time. The “gee, we just killed that” is not part of the process. Sorry, mystics.

Let me offer several observations:

- Google, like any alleged monopoly, faces significant management challenges. Moving information within such an enterprise is difficult. For an organization with a Foosball culture, the task may be a bit outside the wheelhouse of most young people and individuals who are engineers, not presidents of fraternities or sororities.

- The organization is under stress. The pressure is financial because controlling the cost of the plumbing is a reasonably difficult undertaking. Second, there is technical pressure. Google itself made clear that it was in Red Alert mode and keeps adding flashing lights with each and every misstep the firm’s wizards make. These range from contentious relationships with mere governments to individual staff member who grumble via internal emails, angry Googler public utterances, or from observed behavior at conferences. Body language does speak sometimes.

- The approach to smart software is remarkable. Individuals in the UK pontificate. The Mountain View crowd reassures and smiles — a lot. (Personally I find those big, happy looks a bit tiresome, but that’s a dinobaby for you.)

Net net: The write up does not address the issue that Google happily exploits. The company lacks the mental rigor setting and applying editorial policies requires. SEO is good enough to index. Therefore, fake books are certainly A-OK for now.

Stephen E Arnold, April 12, 2024

Information: Cheap, Available, and Easy to Obtain

April 9, 2024

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

I worked in Sillycon Valley and learned a few factoids I found somewhat new. Let me highlight three. First, a person with whom my firm had a business relationship told me, “Chinese people are Chinese for their entire life.” I interpreted this to mean that a person from China might live in Mountain View, but that individual had ties to his native land. That makes sense but, if true, the statement has interesting implications. Second, another person told me that there was a young person who could look at a circuit board and then reproduce it in sufficient detail to draw a schematic. This sounded crazy to me, but the individual took this person to meetings, discussed his company’s interest in upcoming products, and asked for briefings. With the delightful copying machine in tow, this person would have information about forthcoming hardware, specifically video and telecommunications devices. And, finally, via a colleague I learned of an individual who was a naturalized citizen and worked at a US national laboratory. That individual swapped hard drives in photocopy machines and provided them to a family member in his home town in Wuhan. Were these anecdotes true or false? I assumed each held a grain of truth because technology adepts from China and other countries comprised a significant percentage of the professionals I encountered.

Information flows freely in US companies and other organizational entities. Some people bring buckets and collect fresh, pure data. Thanks, MSFT Copilot. If anyone knows about security, you do. Good enough.

I thought of these anecdotes when I read an allegedly accurate “real” news story called “Linwei Ding Was a Google Software Engineer. He Was Also a Prolific Thief of Trade Secrets, Say Prosecutors.” The subtitle is a bit more spicy:

U.S. officials say some of America’s most prominent tech firms have had their virtual pockets picked by Chinese corporate spies and intelligence agencies.

The write up, which may be shaped by art history majors on a mission, states:

Court records say he had others badge him into Google buildings, making it appear as if he were coming to work. In fact, prosecutors say, he was marketing himself to Chinese companies as an expert in artificial intelligence — while stealing 500 files containing some of Google’s most important AI secrets…. His case illustrates what American officials say is an ongoing nightmare for U.S. economic and national security: Some of America’s most prominent tech firms have had their virtual pockets picked by Chinese corporate spies and intelligence agencies.

Several observations about these allegedly true statements are warranted this fine spring day in rural Kentucky:

- Some managers assume that when an employee or contractor signs a confidentiality agreement, the employee will abide by that document. The problem arises when the person shares information with a family member, a friend from school, or with a company paying for information. That assumption underscores what might be called “uninformed” or “naive” behavior.

- The language barrier and certain cultural norms lock out many people who assume idle chatter and obsequious behavior signals respect and conformity with what some might call “US business norms.” Cultural “blindness” is not uncommon.

- Individuals may possess technical expertise unknown to colleagues and contracting firms offering body shop services. Armed with knowledge of photocopiers in certain US government entities, swapping out a hard drive is no big deal. A failure to appreciate an ability to draw a circuit leads to similar ineptness when discussing confidential information.

America operates in a relatively open manner. I have lived and worked in other countries, and that openness often allows information to flow. Assumptions about behavior are not based on an understanding of the cultural norms of other countries.

Net net: The vulnerability is baked in. Therefore, information is often easy to get, difficult to keep privileged, and often aided by companies and government agencies. Is there a fix? No, not without a bit more managerial rigor in the US. Money talks, moving fast and breaking things makes sense to many, and information seeps, maybe floods, from the resulting cracks. Whom does one trust? My approach: Not too many people regardless of background, what people tell me, or what I believe as an often clueless American.

Stephen E Arnold, April 9, 2024

AI and Job Wage Friction

April 1, 2024

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

I read again “The Jobs Being Replaced by AI – An Analysis of 5M Freelancing Jobs,” published in February 2024 by Bloomberg (the outfit interested in fiddled firmware on motherboards). The main idea in the report is that AI boosted a number of freelance jobs. What are the jobs where AI has not (as yet) added friction to the money making process. Here’s the list of jobs NOT impeded by smart software:

Accounting

Backend development

Graphics design

Market research

Sales

Video editing and production

Web design

Web development

Other sources suggest that “Accounting” may be targeted by an AI-powered efficiency expert. I want to watch how this profession navigates the smart software in what is often a repetitive series of eye glazing steps.

Thanks, MSFT Copilot. How are doing doing with your reorganization? Running smoothly? Yeah. Smoothly.

Now to the meat of the report: What professions or jobs were the MOST affected by AI. From the cited write up, these are:

Customer service (the exciting, long suffering discipline of chatbots)

Social media marketing

Translation

Writing

The write up includes another telling chunk of data. AI has apparently had an impact on the amount of money some customers were willing to pay freelancers or gig workers. The jobs finding greater billing friction are:

Backend development

Market research

Sales

Translation

Video editing and production

Web development

Writing

The article contains quite a bit of related information. Please, consult the original for a number of almost unreadable graphics and tabular data. I do want to offer several observations:

- One consequence of AI, if the data in this report are close enough for horseshoes, is that smart software drives down what customers will pay for a wide range of human centric services. You don’t lose your job; you just get a taste of Victorian sweat shop management thinking

- Once smart software is perceived as reasonably capable, demand and pay for good enough translation, smart software is embraced. My view is that translation services are likely to be a harbinger of how AI will affect other jobs. AI does not have to be great; it just has to be perceived as okay. Then. Bang. Hasta la vista human translators except for certain specialized functions.

- Data like the information in the Bloomberg article provide a handy road map for AI developers. The jobs least affected by AI become targets for entrepreneurs who find that low-hanging fruit like translation have been picked. (Accountants, I surmise, should not relax to much.)

Net net: The wage suppression angle and the incremental adoption of AI followed by quick adoption are important ideas to consider when analyzing the economic ripples of AI.

Stephen E Arnold, April 1, 2024

AI Proofing Tools in Higher Education Limbo

March 26, 2024

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

Where is the line between AI-assisted plagiarism and a mere proofreading tool? That is something universities really should have decided by now. Those that have not risk appearing hypocritical and unjust. For example, the University of North Georgia (UNG) specifically recommends students use Grammarly to help proofread their papers. And yet, as News Nation reports, a “Student Fights AI Cheating Allegations for Using Grammarly” at that school.

The trouble began when Marley Stevens’ professor ran her paper through plagiarism-detection software Turnitin, which flagged it for an AI violation. Apparently that (ironically) AI-powered tool did not know Grammarly was on the university’s “nice” list. But surely the charge of cheating was reversed once human administrators got involved, right? Nope. Writer Damita Memezes tells us:

“‘I’m on probation until February 16 of next year. And this started when he sent me the email. It was October. I didn’t think that now in March of 2024, that this would still be a big thing that was going on,’ Stevens said. Despite Grammarly being recommended on the University of North Georgia’s website, Stevens found herself embroiled in battle to clear her name. The tool, briefly removed from the school’s website, later resurfaced, adding to the confusion surrounding its acceptable usage despite the software’s utilization of generative AI. ‘I have a teacher this semester who told me in an email like “yes use Grammarly. It’s a great tool.” And they advertise it,’ Stevens said. … Despite Stevens’ appeal and subsequent GoFundMe campaign to rectify the situation, her options seem limited. The university’s stance, citing the absence of suspension or expulsion, has left her in a bureaucratic bind.”

Grammarly’s Jenny Maxwell defends the tool and emphasizes her company’s transparency around its generative components. She suggests colleges and universities update their assessment methods to address evolving tech like Grammarly. For good measure, we would add Microsoft Word’s Copilot and Google Chrome’s "help me write" feature. Shouldn’t schools be training students in the responsible use of today’s technology? According to UNG, yes. And also, no.

This means that if you use Word and its smart software, you may be a cheater. No need to wait until you go to work at a blue chip consulting firm. You are working on your basic consulting skills.

Cynthia Murrell, March 26, 2024

Can Ma Bell Boogie?

March 25, 2024

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

AT&T provides numerous communication and information services to the US government and companies. People see the blue and white trucks with obligatory orange cones and think nothing about their presence. Decades after Judge Green rained on the AT&T monopoly parade, the company has regained some of its market chutzpah. The old-line Bell heads knew that would happen. One reason was the simple fact that communications services have a tendency to pool; that is, online, for instance, wants to be a monopoly. Like water, online and communication services seek the lowest level. One can grouse about a leaking basement, but one is complaining about a basic fact. Complain away, but the water pools. Similarly AT&T benefits and knows how to make the best of this pooling, consolidating, and collecting reality.

I do miss the “old” AT&T. Say what you will about today’s destabilizing communications environment, just don’t forget that the pre-Judge Green world produced useful innovations, provided hardware that worked, and made it possible for some government functions to work much better than those operations perform today.

Thanks, MSFT, it seems you understand ageing companies which struggle in the midst of the cyber whippersnappers.

But what’s happened?

In February 2024, AT&T experienced an outage. The redundant, fail-safe, state-of-the-art infrastructure failed. “AT&T Cellular Service Restored after Daylong Outage; Cause Still Unknown” reported:

AT&T said late Thursday [February 24, 2024] that based on an initial review, the outage was “caused by the application and execution of an incorrect process used as we were expanding our network, not a cyber attack.” The company will continue to assess the outage.

What do we publicly know about this remarkable event a month ago? Not much. I am not going to speculate how a single misstep can knock out AT&T, but it raises some questions about AT&T’s procedures, its security, and, yes, its technical competence. The AT&T Ashburn data center is an interesting cluster of facilities. Could it be “knocked offline”? My concern is that the answer to this question is, “You bet your bippy it could.”

A second interesting event surfaced as well. AT&T suffered a mysterious breach which appears to have compromised data about millions of “customers.” And “AT&T Won’t Say How Its Customers’ Data Spilled Online.” Here’s a statement from the report of the breach:

When reached for comment, AT&T spokesperson Stephen Stokes told TechCrunch in a statement: “We have no indications of a compromise of our systems. We determined in 2021 that the information offered on this online forum did not appear to have come from our systems. This appears to be the same dataset that has been recycled several times on this forum.”

Leaked data are no big deal and the incident remains unexplained. The AT&T system went down essential at one fell swoop. Plus there is no explanation which resonates with my understanding of the Bell “way.”

Some questions:

- What has AT&T accomplished by its lack of public transparency?

- Has the company lost its ability to manage a large, dynamic system due to cost cutting?

- Is a lack of training and perhaps capable staff undermining what I think of as “mission critical capabilities” for business and government entities?

- What are US regulatory authorities doing to address what is, in my opinion, a threat to the economy of the US and the country’s national security?

Couple the AT&T events with emerging technology like artificial intelligence, will the company make appropriate decisions or create vulnerabilities typically associated with a dominant software company?

Not a positive set up in my opinion. Ma Bell, are you to old and fat to boogie?

Stephen E Arnold, March 26, 2024

Getting Old in the Age of AI? Yeah, Too Bad

March 25, 2024

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

I read an interesting essay called “’Gen X Has Had to Learn or Die: Mid-Career Workers Are Facing Ageism in the Job Market.” The title assumes that the reader knows the difference between Gen X, Gen Y, Gen Z, and whatever other demographic slices marketers and “social” scientists cook up. I recognize one time slice: Dinobabies like me and a category I have labeled “Other.”

Two Gen X dinobabies find themselves out of sync with the younger reptiles’ version of Burning Man. Thanks, MSFT Copilot. Close enough.

The write up, which I think is a work product of a person who realizes that the stranger in a photograph is the younger version of today’s self. “How can that be?” the author of the essay asks. “In my Gen X, Y, or Z mind I am the same. I am exactly the way I was when I was younger.” The write up states:

Gen Xers, largely defined as people in the 44-to-59 age group, are struggling to get jobs.

The write up quotes an expert, Christina Matz, associate professor at the Boston College School of Social Work, and director of the Center on Aging and Work. I believe this individual has a job for now. The essay quotes her observation:

older workers are sometimes perceived as “doddering but dear”. Matz says, “They’re labelled as slower and set in their ways, well-meaning on one hand and incompetent on the other. People of a certain age are considered out-of-touch, and not seen as progressive and innovative.”

I like to think of myself as doddering. I am not sure anyone, regardless of age, will label me “dear.”

But back to the BBC’s essay. I read:

We’re all getting older.

Now that’s an insight!

I noted that the acronym “AI” appears once in the essay. One source is quoted as offering:

… we had to learn the internet, then Web 2.0, and now AI. Gen X has had to learn or die,

Hmmm. Learn of die.

Several observations:

- The write up does not tackle the characteristic of work that strikes me as important; namely, if one is in the Top Tier of people in a particular discipline, jobs will be hard to find. Artificial intelligence will elevate those just below the “must hire” level and allow organizations to replace what once was called “the organization man” with software.

- The discovery that just because a person can use a mobile phone does not give them intellectual super powers. The kryptonite to those hunting for a “job” is that their “package” does not have “value” to an organization seeking full time equivalents. People slap a price tag on themselves and, like people running a yard sale, realize that no one will pay very much for that stack of old time post cards grandma collected.

- The notion of entitlement does not appear in the write up. In my experience, a number of people believe that a company or other type of entity “owes them a living.” Those accustomed to receiving “Also Participated” trophies and “easy” A’s have found themselves on the wrong side of paradise.

My hunch is that these “ageism” write ups are reactions to the gradual adoption of ever more capable “smart” software. I am not sure if the author agrees with me. I am asserting that the examples and comments in the write up are a reaction to the existential threat AI, bots, and embedded machine intelligence finding their way into “systems” today. Probably not.

Now let’s think about the “learn” plank of the essay. A person can learn, adapt, and thrive, right? My personal view is that this is a shibboleth. Oh, oh.

Stephen E Arnold, March 25, 2024

The University of Illinois: Unintentional Irony

March 22, 2024

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

I admit it. I was in the PhD program at the University of Illinois at Champaign-Urbana (aka Chambana). There was nothing like watching a storm build from the upper floors of now departed FAR. I spotted a university news release titled “Americans Struggle to Distinguish Factual Claims from Opinions Amid Partisan Bias.” From my point of view, the paper presents research that says that half of those in the sample cannot distinguish truth from fiction. That’s a fact easily verified by visiting a local chain store, purchasing a product, and asking the clerk to provide the change in a specific way; for example, “May I have two fives and five dimes, please?” Putting data behind personal experience is a time-honored chore in the groves of academe.

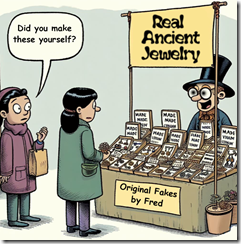

Discerning people can determine “real” from “original fakes.” Well, only half the people can it seems. The problem is defining what’s true and what’s false. Thanks, MSFT Copilot. Keep working on your security. Those breaches are “real.” Half the time is close enough for horseshoes.

Here’s a quote from the write up I noted:

“How can you have productive discourse about issues if you’re not only disagreeing on a basic set of facts, but you’re also disagreeing on the more fundamental nature of what a fact itself is?” — Matthew Mettler, a U. of I. graduate student and co-author of with Jeffery J. Mondak, a professor of political science and the James M. Benson Chair in Public Issues and Civic Leadership at Illinois.

The news release about Mettler’s and Mondak’s research contains this statement:

But what we found is that, even before we get to the stage of labeling something misinformation, people often have trouble discerning the difference between statements of fact and opinion…. “What we’re showing here is that people have trouble distinguishing factual claims from opinion, and if we don’t have this shared sense of reality, then standard journalistic fact-checking – which is more curative than preventative – is not going to be a productive way of defanging misinformation,” Mondak said. “How can you have productive discourse about issues if you’re not only disagreeing on a basic set of facts, but you’re also disagreeing on the more fundamental nature of what a fact itself is?”

But the research suggests that highly educated people cannot differentiate made up data from non-weaponized information. What struck me is that Harvard’s Misinformation Review published this U of I research that provides a road map to fooling peers and publishers. Harvard University, like Stanford University, has found that certain big-time scholars violate academic protocols.

I am delighted that the U of I research is getting published. My concern is that the Misinformation Review does not find my laughing at its Misinformation Review to their liking. Harvard illustrates that academic transgressions cannot be identified by half of those exposed to the confections of up-market academics.

Should Messrs Mettler and Mondak have published their research in another journal? That a good question, but I am no longer convinced that professional publications have more credibility than the outputs of a content farm. Such is the erosion of once-valued norms. Another peril of thumb typing is present.

Stephen E Arnold, March 22, 2024

Software Failure: Why Problems Abound and Multiply Like Gerbils

March 19, 2024

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

I read “Why Software Projects Fail” after a lunch at which crappy software and lousy products were a source of amusement. The door fell off what?

What’s interesting about the article is that it contains a number of statements which resonated with me. I recommend the article, but I want to highlight several statements from the essay. These do a good job of explaining why small and large projects go off the rails. Within the last 12 months I witnessed one project get tangled in solving a problem that existed 15 years ago. Today not so much. The team crafted the equivalent of a Greek Corinthian helmet from the 8th century BCE. Another project infused with AI and vision of providing a “new” approach to security wobble between and among a telecommunications approach, an email approach, and an SMS approach with bells and whistles only a science fiction fan would appreciate. Both of these examples obtained funding; neither set out to build a clown car. What happened? That’s where “Why Projects Fail?” becomes relevant.

Thanks, MSFT Copilot. You have that MVP idea nailed with the recent Windows 11 update, don’t you. Good enough I suppose.

Let’s look at three passages from the essay, shall we?

Belief in One’s Abilities or I Got an Also-Participated Ribbon in Middle School

Here’s the statement from the essay:

One of the things that I’ve noticed is that developers often underestimate not just the complexity of tasks, but there’s a general overconfidence in their abilities, not limited by programming:

- Overconfidence in their coding skills.

- Overconfidence in learning new technologies.

- Overconfidence in our abstractions.

- Overconfidence in external dependencies, e.g., third-party services or some open-source library.

My comment: Spot on. Those ribbons built confidence, but they mean nothing.

Open Source Is Great Unless It Has Been Screwed Up, Become a Malware Delivery Vehicle, or Just Does Not Work

Here’s the statement from the essay:

… anything you do not directly control is a risk of hidden complexity. The assumption that third-party services, libraries, packages, or APIs will work as expected without bugs is a common oversight.

My view is that “complexity” is kicked around as if everyone held a shared understanding of the term. There are quite different types of complexity. For software, there is the complexity of a simple process created in Assembler but essentially impenetrable to a 20-something from a whiz-bang computer science school. There is the complexity of software built over time by attention deficit driven people who do not communicate, coordinate, or care what others are doing, will do, or have done. Toss in the complexity of indifferent, uninformed, or uninterested “management,” and you get an exciting environment in which to “fix up” software. The cherry on top of this confection is that quite a bit of software is assumed to be good. Ho ho ho.

The Real World: It Exists and Permeates

I liked this statement:

Technology that seemed straightforward refuses to cooperate, external competitors launch similar ideas, key partners back out, and internal business stakeholders focus more on the projects that include AI in their name. Things slow down, and as months turn into years, enthusiasm wanes. Then the snowball continues — key members leave, and new people join, each departure a slight shift in direction. New tech lead steps in, eager to leave their mark, steering the project further from its original course. At this point, nobody knows where the project is headed, and nobody wants to admit the project has failed. It’s a tough spot, especially when everyone’s playing it safe, avoiding the embarrassment or penalties of admitting failure.

What are the signals that trouble looms? A fumbled ball at the Google or the Apple car that isn’t can be blinking lights. Staff who go rogue on social media or find an ambulance chasing honed law firm can catch some individual’s attention.

The write up contains other helpful observations. Will people take heed? Are you kidding me? Excellence costs money, requires informed judgment, and expertise. Who has time for this with AI calendars, the demands of TikTok and Instagram, and hitting the local coffee shop?

Stephen E Arnold, March 19, 2024

Old Code, New Code: Can You Make It Work Again… Sort Of?

March 18, 2024

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

Even hippy dippy super slick AI start ups have a technical debt problem. It is, in my opinion, no different from the “costs” imposed on outfits like JPMorgan Chase or (heaven help us) AMTRAK. Software which mostly works is subject to two environmental problems. First, the people who wrote the code or made it work that last time catastrophe struck (hello, AT&T, how are those pushed updates working for you now?) move on, quit, or whatever. Second, the technical options for remediating the problem are evolving (how are those security hot fixes working out, Microsoft?).

The helpful father asks an question the aspiring engineer cannot answer. Thus it was when the wizard was a child, and it is when the wizard is working on a modern engineering project. Buildings tip; aircraft lose doors and wheels. Software updates kill computers. Self-driving cars cannot. Thanks, MSFT Copilot. Did you get your model airplane to fly when you were a wee lad? I think I know the answer.

I thought about this problem of the cost of code remediating, fixing, redoing, upgrading or whatever term fast-talking sales engineers use in their Zooms and PowerPoints as I read “The High-Risk Refactoring.” The write up does a good job of explaining in a gentle way what happens when suits authorize making old code like new again. (The suits do not know the agonies of the original developers, but why should “history” intrude on a whiz bang GenX or GenY management type?

The article says:

it’s highly important to ensure the system works the same way after the swap with the new code. In that regard, immediately spotting when something breaks throughout the whole refactoring process is very helpful. No one wants to find that out in production.

No kidding.

In most cases, there are insufficient skilled people and money to create a new or revamped system, get it up and running in parallel for an appropriate period of time, identify the problems, remediate them, and then make the cut over. People buy cars this way, but that’s not how most organizations, regardless of size, “do” software. Okay, the take your car in, buy a new one, and drive off will not work in today’s business environment.

The write up focuses on what most organizations do; that is, write or fix new code and stick it into a system. There may or may not be resources for a staging server, but the result is the same. The old software has been “fixed” and the documentation is “sort of written” and people move on to other work or in the case of consulting engineering firms, just get replaced by a new, higher margin professional.

The write up takes a different approach and concludes with four suggestions or questions to ask. I quote:

“Refactor if things are getting too complicated, but stop if can’t prove it works.

Accompany new features with refactoring for areas you foresee to be subject to a change, but copy-pasting is ok until patterns arise.

Be proactive in finding new ways to ensure refactoring predictability, but be conservative about the assumption QA will find all the bugs.

Move business logic out of busy components, but be brave enough to keep the legacy code intact if the only argument is “this code looks wrong”.

These are useful points. I would like to suggest some bright white lines for those who have to tackle an IRS-mainframe- or AT&T-billing system type of challenge as well as tweaking an artificial intelligence solution to respond to those wonky multi-ethnic images Google generated in order to allow the Sundar & Prabhakar Comedy Team to smile sheepishly and apologize again for lousy software.

Are you ready? Let’s go:

- Fixes add to the complexity of the code base. As time goes stumbling forward, the complexity of the software becomes greater. The cost of making sure the fix works and does not create exciting dependency behavior goes up. Thus, small fixes “cost” more, and these costs are tough to control.

- The safest fixes are “wrappers”; that is, no one in his or her right mind wants to change software written in 1978 for a machine no longer in production by the manufacturer. Therefore, new software is written to interact in a “safe” way with the original software. The new code “fixes up” the problem without screwing up what grandpa programmer wrote almost half a century ago. The problem is that “wrappers” tend to slow stuff down. The fix is to say one will optimize the system while one looks for a new project or job.

- The software used for “fixing” a problem is becoming the equivalent of repairing an aircraft component with Dawn laundry detergent. The “fix” is cheap, easy to use, and good enough. The software equivalent of this Dawn solution is that it will not stand the test of time. Instead of code crafted in good old COBOL or Assembler, we have some Fancy Dan tools which may fall out of favor in a matter of months, not decades.

Many projects result in better, faster, and cheaper. The reminder “Pick two” is helpful.

Net net: Fixing up lousy or flawed software is going to increase risks and costs. The question asked by bean counters is, “How much?” The answer is, “No one knows until the project is done … if ever.”

Stephen E Arnold, March 18, 2024