Yep, the Old Internet Is Gone. Learn to Love the New Internet

August 1, 2024

This essay is the work of a dumb humanoid. No smart software required.

This essay is the work of a dumb humanoid. No smart software required.

The market has given the Google the green light to restrict information. The information highway has a new on ramp. If you want content created by people who were not compensated, you have to use Google search. Toss in the advertising system and that good old free market is going to deliver bumper revenue to stakeholders.

Online search is a problem. Here’s an old timer like me who broke his leg. The young wizard who works at a large online services firm explains that I should not worry. By the time my leg heals, I will be dead. Happy thoughts from one of those Gen somethings. Thanks, MSFT Copilot. How your security systems today?

What about users? The reality is that with Google the default search system in Apple iPhones, the brand that has redefined search and retrieval to mean “pay to play,” what’s the big deal?

Years ago I explained in numerous speeches and articles in publications like Online Magazine that online fosters the creation of centralized monopolistic information services. Some information professionals dismissed my observation as stupid. The general response was that online would generate benefits. I agree. But there were a few downsides. I usually pointed to the duopoly in online for fee legal information. I referenced the American Chemical Society’s online service Chemical Abstracts. I even pointed out that outfits like Predicasts and the New York Times would have a very, very tough time creating profitable information centric standalone businesses. The centralization or magnetic pull of certain online services would make generating profits very expensive.

So where are we now? I read “Reddit, Google, and the Real Cost of the AI Data Rush.” The article is representative of “real” journalists’, pundits’, and some regulators’ understanding of online information. The write up says:

Google, like Reddit, owes its existence and success to the principles and practices of the open web, but exclusive arrangements like these mark the end of that long and incredibly fruitful era. They’re also a sign of things to come. The web was already in rough shape, reduced over the last 15 years by the rise of walled-off platforms, battered by advertising consolidation, and polluted by a glut of content from the AI products that used it for training. The rise of AI scraping threatens to finish the job, collapsing a flawed but enormously successful, decades-long experiment in open networking and human communication to a set of antagonistic contracts between warring tech firms.

I want to point out that Google bought rights to Reddit. If you want to search Reddit, you use Google. Because Reddit is a high traffic site, users have to use Google. Guess what? Most online users do not care. Search means Google. Information access means Google. Finding a restaurant means Google. Period.

Google has become a center of gravity in the online universe. One can argue that Google is the Internet. In my monograph Google Version 2.0: The Calculating Predator that is exactly what some Googlers envisioned for the firm. Once a user accesses Google, Google controls the information world. One can argue that Meta and TikTok are going to prevent that. Some folks suggest that one of the AI start ups will neutralize Google’s centralized gravitational force. Google is a distributed outfit. Think of it as like the background radiation in our universe. It is just there. Live with it.

Google has converted content created by people who were not compensated into zeros and ones that will enhance its magnetic pull on users.

Several observations:

- Users were so enamored of a service which could show useful results from the quite large and very disorganized pools of digital information that it sucked the life out of its competitors.

- Once a funding source got the message through to the Backrub boys that they had to monetize, the company obtained inspiration from the Yahoo pay to play model which Yahoo acquired from Overture.com, formerly GoTo.com. That pay to play thing produces lots of money when there is traffic. Google was getting traffic.

- Regulators ignored Google’s slow but steady march to information dominance. In fact, some regulatory professionals with whom I spoke thought Google was the cat’s pajamas and asked me if I could get them Google T shirts for their kids. Google was not evil; it was fund; it was success.

- Almost the entire world’s intelligence professionals relay on Google for OSINT. If you don’t know what that means, forget the term. Knowing the control Google can exert by filtering information on a topic will probably give you a tummy ache.

The future is going to look exactly like the world of online in the year 1980. Google and maybe a couple of smaller also rans will control access to digital information. To get advertising free and to have a shot at bias free answers to online queries, users will have to pay. The currency will be watching advertising or subscribing to a premium service. The business model of Dialog Information Services, SDC, DataStar, and Dialcom is coming back. The prices will inflate. Control of information will be easy. And shaping or weaponizing content flow from these next generation online services will be too profitable to resist. Learn to love Google. It is more powerful than a single country’s government. If a country gets too frisky for Google’s liking, the company has ways to evade issues that make it uncomfortable.

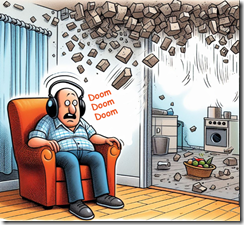

The cartoon in this blog post summarizes my view of the situation. A fix will take a long time. I will be pushing up petunias before the problems of online search and the Information Superhighway are remediated.

Stephen E Arnold, August 1, 2024

Prompt Tips and Query Refinements

July 29, 2024

Generative AI is paving the way for more automation, smarter decisions, and (possibly) an easier world. AI is still pretty stupid, however, and it needs to be hand fed information to make it work well. Dr. Lance B. Eliot is an AI expert and he contributed, “The Best Engineering Techniques For Getting The Most Out Of Generative AI” for Forbes.

Eliot explains the prompt engineering is the best way to make generative AI. He developed a list of how to write prompts and related skills. The list is designed to be a quick, easy tutorial that is also equipped with links for more information related to the prompt. Eliot’s first tip is to keep the prompt simple, direct, and obvious, otherwise the AI will misunderstand your intent.

He the rattles of a bunch of rhetoric that reads like it was written by generative AI. Maybe it was? In short, it’s good to learn how to write prompts to prepare for the future. He runs through the list alphabetically, then if that’s enough Eliot lists the prompts numerically:

“I didn’t number them because I was worried that the numbering would imply a semblance of importance or priority. I wanted the above listing to seem that all the techniques are on an equal footing. None is more precious than any of the others.

Lamentably, not having numbers makes life harder when wanting to quickly refer to a particular prompt engineering technique. So, I am going to go ahead and show you the list again and this time include assigned numbers. The list will still be in alphabetical order. The numbering is purely for ease of reference and has no bearing on priority or importance.”

The list is rundown of psychological and intercommunication methods used by humans. A lot of big words are used, but the explanations were written by a tech-savvy expert for his fellow tech people. In layman’s terms, the list explains that anything technique will work. Here’s one from me: use generative AI to simplify the article. Here’s a paradox prompt: if you feed generative AI a prompt written by generative AI will it explode?

Whitney Grace, July 29, 2024

Stop Indexing! And Pay Up!

July 17, 2024

This essay is the work of a dinobaby. Unlike some folks, no smart software improved my native ineptness.

This essay is the work of a dinobaby. Unlike some folks, no smart software improved my native ineptness.

I read “Apple, Nvidia, Anthropic Used Thousands of Swiped YouTube Videos to Train AI.” The write up appears in two online publications, presumably to make an already contentious subject more clicky. The assertion in the title is the equivalent of someone in Salem, Massachusetts, pointing at a widower and saying, “She’s a witch.” Those willing to take the statement at face value would take action. The “trials” held in colonial Massachusetts. My high school history teacher was a witchcraft trial buff. (I think his name was Elmer Skaggs.) I thought about his descriptions of the events. I recall his graphic depictions and analysis of what I recall as “dunking.” The idea was that if a person was a witch, then that person could be immersed one or more times. I think the idea had been popular in medieval Europe, but it was not a New World innovation. Me-too is a core way to create novelty. The witch could survive being immersed for a period of time. With proof, hanging or burning were the next step. The accused who died was obviously not a witch. That’s Boolean logic in a pure form in my opinion.

The Library in Alexandria burns in front of people who wanted to look up information, learn, and create more information. Tough. Once the cultural institution is gone, just figure out the square root of two yourself. Thanks, MSFT Copilot. Good enough.

The accusations and evidence in the article depict companies building large language models as candidates for a test to prove that they have engaged in an improper act. The crime is processing content available on a public network, indexing it, and using the data to create outputs. Since the late 1960s, digitizing information and making it more easily accessible was perceived as an important and necessary activity. The US government supported indexing and searching of technical information. Other fields of endeavor recognized that as the volume of information expanded, the traditional methods of sitting at a table, reading a book or journal article, making notes, analyzing the information, and then conducting additional research or writing a technical report was simply not fast enough. What worked in a medieval library was not a method suited to put a satellite in orbit or perform other knowledge-value tasks.

Thus, online became a thing. Remember, we are talking punched cards, mainframes, and clunky line printers one day there was the Internet. The interest in broader access to online information grew and by 1985, people recognized that online access was useful for many tasks, not just looking up information about nuclear power technologies, a project I worked on in the 1970s. Flash forward 50 years, and we are upon the moment one can read about the “fact” that Apple, Nvidia, Anthropic Used Thousands of Swiped YouTube Videos to Train AI.

The write up says:

AI companies are generally secretive about their sources of training data, but an investigation by Proof News found some of the wealthiest AI companies in the world have used material from thousands of YouTube videos to train AI. Companies did so despite YouTube’s rules against harvesting materials from the platform without permission. Our investigation found that subtitles from 173,536 YouTube videos, siphoned from more than 48,000 channels, were used by Silicon Valley heavyweights, including Anthropic, Nvidia, Apple, and Salesforce.

I understand the surprise some experience when they learn that a software script visits a Web site, processes its content, and generates an index (a buzzy term today is large language model, but I prefer the simpler word index.)

I want to point out that for decades those engaged in making information findable and accessible online have processed content so that a user can enter a query and get a list of indexed items which match that user’s query. In the old days, one used Boolean logic which we met a few moments ago. Today a user’s query (the jazzy term is prompt now) is expanded, interpreted, matched to the user’s “preferences”, and a result generated. I like lists of items like the entries I used to make on a notecard when I was a high school debate team member. Others want little essays suitable for a class assignment on the Salem witchcraft trials in Mr. Skaggs’s class. Today another system can pass a query, get outputs, and then take another action. This is described by the in-crowd as workflow orchestration. Others call it, “taking a human’s job.”

My point is that for decades, the index and searching process has been without much innovation. Sure, software scripts can know when to enter a user name and password or capture information from Web pages that are transitory, disappearing in the blink of an eye. But it is still indexing over a network. The object remains to find information of utility to the user or another system.

The write up reports:

Proof News contributor Alex Reisner obtained a copy of Books3, another Pile dataset and last year published a piece in The Atlantic reporting his finding that more than 180,000 books, including those written by Margaret Atwood, Michael Pollan, and Zadie Smith, had been lifted. Many authors have since sued AI companies for the unauthorized use of their work and alleged copyright violations. Similar cases have since snowballed, and the platform hosting Books3 has taken it down. In response to the suits, defendants such as Meta, OpenAI, and Bloomberg have argued their actions constitute fair use. A case against EleutherAI, which originally scraped the books and made them public, was voluntarily dismissed by the plaintiffs. Litigation in remaining cases remains in the early stages, leaving the questions surrounding permission and payment unresolved. The Pile has since been removed from its official download site, but it’s still available on file sharing services.

The passage does a good job of making clear that most people are not aware of what indexing does, how it works, and why the process has become a fundamental component of many, many modern knowledge-centric systems. The idea is to find information of value to a person with a question, present relevant content, and enable the user to think new thoughts or write another essay about dead witches being innocent.

The challenge today is that anyone who has written anything wants money. The way online works is that for any single user’s query, the useful information constitutes a tiny, miniscule fraction of the information in the index. The cost of indexing and responding to the query is high, and those costs are difficult to control.

But everyone has to be paid for the information that individual “created.” I understand the idea, but the reality is that the reason indexing, search, and retrieval was invented, refined, and given numerous life extensions was to perform a core function: Answer a question or enable learning.

The write up makes it clear that “AI companies” are witches. The US legal system is going to determine who is a witch just like the process in colonial Salem. Several observations are warranted:

- Modifying what is a fundamental mechanism for information retrieval may be difficult to replace or re-invent in a quick, cost-efficient, and satisfactory manner. Digital information is loosey goosey; that is, it moves, slips, and slides either by individual’s actions or a mindless system’s.

- Slapping fines and big price tags on what remains an access service will take time to have an impact. As the implications of the impact become more well known to those who are aggrieved, they may find that their own information is altered in a fundamental way. How many research papers are “original”? How many journalists recycle as a basic work task? How many children’s lives are lost when the medical reference system does not have the data needed to treat the kid’s problem?

- Accusing companies of behaving improperly is definitely easy to do. Many companies do ignore rules, regulations, and cultural norms. Engineering Index’s publisher leaned that bootleg copies of printed Compendex indexes were available in China. What was Engineering Index going to do when I learned this almost 50 years ago? The answer was give speeches, complain to those who knew what the heck a Compendex was, and talk to lawyers. What happened to the Chinese content pirates? Not much.

I do understand the anger the essay expresses toward large companies doing indexing. These outfits are to some witches. However, if the indexing of content is derailed, I would suggest there are downstream consequences. Some of those consequences will make zero difference to anyone. A government worker at a national lab won’t be able to find details of an alloy used in a nuclear device. Who cares? Make some phone calls? Ask around. Yeah, that will work until the information is needed immediately.

A student accustomed to looking up information on a mobile phone won’t be able to find something. The document is a 404 or the information returned is an ad for a Temu product. So what? The kid will have to go the library, which one hopes will be funded, have printed material or commercial online databases, and a librarian on duty. (Good luck, traditional researchers.) A marketing team eager to get information about the number of Telegram users in Ukraine won’t be able to find it. The fix is to hire a consultant and hope those bright men and women have a way to get a number, a single number, good, bad, or indifferent.)

My concern is that as the intensity of the objections about a standard procedure for building an index escalate, the entire knowledge environment is put at risk. I have worked in online since 1962. That’s a long time. It is amazing to me that the plumbing of an information economy has been ignored for a long time. What happens when the companies doing the indexing go away? What happens when those producing the government reports, the blog posts, or the “real” news cannot find the information needed to create information? And once some information is created, how is another person going to find it. Ask an eighth grader how to use an online catalog to find a fungible book. Let me know what you learn? Better yet, do you know how to use a Remac card retrieval system?

The present concern about information access troubles me. There are mechanisms to deal with online. But the reason content is digitized is to find it, to enable understanding, and to create new information. Digital information is like gerbils. Start with a couple of journal articles, and one ends up with more journal articles. Kill this access and you get what you wanted. You know exactly who is the Salem witch.

Stephen E Arnold, July 17, 2024

x

x

x

x

x

x

Does Google Have a Monopoly? Does AI Search Make a Difference?

July 9, 2024

I read “2024 Zero-Click Search Study: For Every 1,000 EU Google Searches, Only 374 Clicks Go to the Open Web. In the US, It’s 360.” The write up begins with caveats — many caveats. But I think I am not into the search engine optimization and online advertising mindset. As a dinobaby, I find the pursuit of clicks in a game controlled by one outfit of little interest.

Is it possible that what looks like a nice family vacation place is a digital roach motel? Of course not! Thanks, MSFT Copilot. Good enough.

Let’s answer the two questions the information in the report from the admirably named SparkToro presents. In my take on the article, the charts, the buzzy jargon, the answer to the question, “Does Google Have a Monopoly?” the answer is, “Wow, do they.”

The second question I posed is, “Does AI Search Make a Difference in Google Traffic?’ the answer is, “A snowball’s chance in hell is better.”

The report and analysis takes me to close enough for horse shoes factoids. But that’s okay because the lack of detailed, reliable data is part of the way online operates. No one really knows if the clicks from a mobile device are generated by a nepo baby with money to burn or a bank of 1,000 mobile devices mindlessly clicking on Web destinations. Factoids about online activity are, at best, fuzzy. I think SEO experts should wear T shirts and hats with this slogan, “Heisenberg rocks. I am uncertain.

I urge you to read and study the SparkToro analysis. (I love that name. An electric bull!)

The article points out that Google gets a lot of clicks. Here’s a passage which knits together several facts from the study:

Google gets 1/3 of the clicks. Imagine a burger joint selling 33 percent of the burgers worldwide. Could they get more? Yep. How much more:

Equally concerning, especially for those worried about Google’s monopoly power to self-preference their own properties in the results, is that almost 30% of all clicks go to platforms Google owns. YouTube, Google Images, Google Maps, Google Flights, Google Hotels, the Google App Store, and dozens more means that Google gets even more monetization and sector-dominating power from their search engine. Most interesting to web publishers, entrepreneurs, creators, and (hopefully) regulators is the final number: for every 1,000 searches on Google in the United States, 360 clicks make it to a non-Google-owned, non-Google-ad-paying property. Nearly 2/3rds of all searches stay inside the Google ecosystem after making a query.

The write up also presents information which suggests that the European Union’s regulations don’t make much difference in the click flow. Sorry, EU. You need another approach, perhaps?

In the US, users of Google have a tough time escaping what might be colorfully named the “digital roach motel.”

Search behavior in both regions is quite similar with the exception of paid ads (EU mobile searchers are almost 50% more likely to click a Google paid search ad) and clicks to Google properties (where US searchers are considerably more likely to find themselves back in Google’s ecosystem after a query).

The write up presented by SparkToro (Is it like the energizer bunny?) answers a question many investors and venture firms with stakes in smart software are asking: “Is Google losing search traffic? The answer is, “Nope. Not a chance.”

According to Datos’ panel, Google’s in no risk of losing market share, total searches, or searches per searcher. On all of these metrics they are, in fact, stronger than ever. In both the US and EU, searches per searcher are rising and, in the Spring of 2024, were at historic highs. That data doesn’t fit well with the narrative that Google’s cost themselves credibility or that Internet users are giving up on Google and seeking out alternatives. … Google continues to send less and less of its ever-growing search pie to the open web…. After a decline in 2022 and early 2023, Google’s back to referring a historically high amount of its search clicks to its own properties.

AI search has not been the game changer for which some hoped.

Net net: I find it interesting that data about what appears to be a monopoly is so darned sketchy after more than two decades of operation. For Web search start ups, it may be time to rethink some of those assertions in those PowerPoint decks.

Stephen E Arnold, July 9, 2024

Encryption Battles Continue

June 4, 2024

This essay is the work of a dinobaby. Unlike some folks, no smart software improved my native ineptness.

This essay is the work of a dinobaby. Unlike some folks, no smart software improved my native ineptness.

Privacy protections are great—unless you are law-enforcement attempting to trace a bad actor. India has tried to make it easier to enforce its laws by forcing messaging apps to track each message back to its source. That is challenging for a platform with encryption baked in, as Rest of World reports in, “WhatsApp Gives India an Ultimatum on Encryption.” Writer Russell Brandom tells us:

“IT rules passed by India in 2021 require services like WhatsApp to maintain ‘traceability’ for all messages, allowing authorities to follow forwarded messages to the ‘first originator’ of the text. In a Delhi High Court proceeding last Thursday, WhatsApp said it would be forced to leave the country if the court required traceability, as doing so would mean breaking end-to-end encryption. It’s a common stance for encrypted chat services generally, and WhatsApp has made this threat before — most notably in a protracted legal fight in Brazil that resulted in intermittent bans. But as the Indian government expands its powers over online speech, the threat of a full-scale ban is closer than it’s been in years.”

And that could be a problem for a lot of people. We also learn:

“WhatsApp is used by more than half a billion people in India — not just as a chat app, but as a doctor’s office, a campaigning tool, and the backbone of countless small businesses and service jobs. There’s no clear competitor to fill its shoes, so if the app is shut down in India, much of the digital infrastructure of the nation would simply disappear. Being forced out of the country would be bad for WhatsApp, but it would be disastrous for everyday Indians.”

Yes, that sounds bad. For the Electronic Frontier Foundation, it gets worse: The civil liberties organization insists the regulation would violate privacy and free expression for all users, not just suspected criminals.

To be fair, WhatsApp has done a few things to limit harmful content. It has placed limits on message forwarding and has boosted its spam and disinformation reporting systems. Still, there is only so much it can do when enforcement relies on user reports. To do more would require violating the platform’s hallmark: its end-to-end encryption. Even if WhatsApp wins this round, Brandom notes, the issue is likely to come up again when and if the Bharatiya Janata Party does well in the current elections.

Cynthia Murrell, June 4, 2024

Spot a Psyop Lately?

June 3, 2024

This essay is the work of a dinobaby. Unlike some folks, no smart software improved my native ineptness.

This essay is the work of a dinobaby. Unlike some folks, no smart software improved my native ineptness.

Psyops or psychological operations is also known as psychological warfare. It’s defines as actions used to weaken an enemy’s morale. Psyops can range from simple propaganda poster to a powerful government campaign. According to Annalee Newitz on her Hypothesis Buttondown blog, psyops are everywhere and she explains: “How To Recognize A Psyop In Three Easy Steps.”

Newitz smartly condenses the history of American psyops into a paragraph: it’s a mixture of pulp fiction tropes, advertising techniques, and pop psychology. In the twentieth century, US military harnessed these techniques to make messages to hurt, demean, and distract people. Unlike weapons, psyops can be avoided with a little bit of critical thinking.

The first step is to pay attention when people claim something is “anti-American.” The term “anti-American” can be interpreted in many ways, but it comes down to media saying one group of people (foreign, skin color, sexual orientation, etc.) is against the American way of life.

The second step is spreading lies with hints of truth. Newitz advises to read psychological warfare military manuals and uses an example of leaflets the Japanese dropped on US soldiers in the Philippines. The leaflets warned the soldiers about venomous snakes in jungles and they were signed by with “US Army.” Soldiers were told the leaflets were false, but it made them believe there were coverups:

“Psyops-level lies are designed to destabilize an enemy, to make them doubt themselves and their compatriots, and to convince them that their country’s institutions are untrustworthy. When psyops enter culture wars, you start to see lies structured like this snake “warning.” They don’t just misrepresent a specific situation; they aim to undermine an entire system of beliefs.”

The third step is the easiest to recognize and the most extreme: you can’t communicate with anyone who says you should be dead. Anyone who believes you should be dead is beyond rational thought. Her advice is to ignore it and not engage.

Another way to recognize psyops tactics is to question everything. Thinking isn’t difficult, but thinking critically takes practice.

Whitney Grace, June 3, 2024

Guarantees? Sure … Just Like Unlimited Data Plans

May 30, 2024

This essay is the work of a dinobaby. Unlike some folks, no smart software improved my native ineptness.

This essay is the work of a dinobaby. Unlike some folks, no smart software improved my native ineptness.

I loved this story: “T-Mobile’s Rate Hike Raises Ire over Price Lock Guarantees.” The idea that something is guaranteed today is a hoot. Remember “unlimited data plans”? I think some legal process determined that unlimited did not mean without limits. This is not just wordsmithing; it is probably a behavior which, if attempted in certain areas of Sicily, would result in something quite painful. Maybe a beating, a knife in the ribs, or something more colorful? But today, are you kidding me?

The soon-to-be-replaced-by-a-chatbot AI entity is reassuring a customer about a refund. Is the check in the mail? Will the sales professional take the person with whom he is talking to lunch? Absolutely. This is America, a trust outfit for sure. Thanks, MSFT Copilot. Working on security today?

The write up points out:

…in T-Mobile’s case, customers are seething because T-Mobile is raising prices on plans that were offered with “guarantees” they wouldn’t go up, such as T-Mobile One plans.

Unusual? No, visit a big time grocery store. Select 10 items at random. Do the prices match what was displayed on the shelves? Let me know. Our local outfit is batting 10 percent incorrect pricing per 10 items. Does the manager care? Sure, but does the pricing change or the database errors get adjusted. Ho ho ho.

The article reported:

“Clearly this is bad optics for T-Mobile since it won many people over as the ‘non-corporate’ un-carrier,” he [Eric Michelson, a social and digital media strategist] said.

Imagine a telecommunications company raising prices and refusing to provide specific information about which customers get the opportunity to pay more for service.

Several observations:

- Promises mean zero. Ask people trying to get reimbursed for medical expenses or for post-tornado house repairs

- Clever is more important that behaving in an ethical and responsible manner. Didn’t Google write a check to the US government to make annoying legal matters go away?

- The language warped by marketers and shape shifted by attorneys makes understanding exactly what’s afoot difficult. How about the wording in an omnibus bill crafted by lobbyists and US elected officials’ minions? Definitely crystal clear to some. To others, well, not too clear.

Net net: What’s up with the US government agencies charged with managing corporate behavior and protecting the rights of citizens? Answer: These folks are in meetings, on Zoom calls, or working from home. Please, leave a message.

Stephen E Arnold, May 30, 2024

The Death of the Media: Remember Clay Tablets?

May 24, 2024

This essay is the work of a dinobaby. Unlike some folks, no smart software improved my native ineptness.

This essay is the work of a dinobaby. Unlike some folks, no smart software improved my native ineptness.

Did the home in which you grew from a wee one to a hyperspeed teen have a plaster cast which said, “Home sweet home” or “Welcome” hanging on the wall. My mother had those craft sale treasures everywhere. I have none. The point is that the clay tablets from ancient times were not killed, put out of business, or bankrupted because someone wrote on papyrus, sheep skin, or bits of wood. Eliminating a communications medium is difficult. Don’t believe me? Go to an art fair and let me know if you were unable to spot something made of clay with writing or a picture on it.

I mention these older methods of disseminating a message because I read “Publishers Horrified at New Google AI Feature That Could Kill What’s Left of Journalism.” Really?

The write up states:

… preliminary studies on Google’s use of AI in its search engine has the potential to reduce website traffic by 25 percent, The Associated Press reports. That could be billions in revenue lost, according to an interview with Marc McCollum, chief innovation officer for content creator consultancy Raptive, who was interviewed by the AP.

The idea is that “real” journalism depends on Google for revenue. If the revenue from Google’s assorted ad programs tossing pennies to Web sites goes away, so will the “real” journalism on these sites.

If my dinobaby memory is working, the AP (Associated Press) was supported by newspapers. Then the AP was supported by Google. What’s next? I don’t know, but the clay tablet fellows appear to have persisted. The producers of the tablets probably shifted to tableware. Those who wrote on the tablets learned to deal with ink and sheepskin.

Chilling in the room thinking thoughts of doom. Thanks, MSFT Copilot. Keep following your security recipe.

AI seems to be capable of creating stories like those in Smartnews or one of the AI-powered spam outfits. The information is recycled. But it is good enough. Some students today seem incapable of tearing themselves from their mobile devices to read words. The go-to method for getting information is a TikTok-type service. People who write words may be fighting to make the shift to new media.

One thing is reasonably clear: Journalists and media-mavens are concerned that a person will take an answered produced by a Google-like service. The entering a query approach to information is a “hot medium thing.” Today kicking back and letting video do the work seems to be a winner.

Google, however, has in my opinion been fiddling with search since it “innovated” in its implementation of the GoTo.com/Overture.com approach to “pay to play” search. If you want traffic, buy ads. The more one spends, the more traffic one’s site gets. That’s simple. There are some variations, but the same Google model will be in effect with or without Google little summaries. The lingo may change, but where there are clicks. When there are clicks, advertisers will pay to be there.

Google can, of course, kill its giant Googzilla mom laying golden eggs. That will take some time. Googzilla is big. My theory is that enterprising people with something to say will find a way to get paid for their content outputs regardless of their form. True, there is the cost of paying, but that’s the same hit the clay table took thousands of years ago. But those cast plaster and porcelain art objects are probably on sale at an art fair this weekend.

Observations:

- The fear is palpable. Why not direct it to a positive end? Griping about Google which has had 25 years to do what it wanted to do means Google won’t change too much. Do something to generate money. Complaining is unlikely to produce a result.

- The likelihood Google shaft a large number of outfits and individuals is nearly 99 percent. Thus, moving in a spritely manner may be a good idea. Google is not a sprinter as its reaction to Microsoft’s Davos marketing blitz made clear.

- New things do appear. I am not sure what the next big thing will be. But one must pay attention.

Net net: The sky may be falling. The question is, “How fast?” Another is, “Can you get out of the way?”

Stephen E Arnold, May 24, 2024

A Cultural Black Hole: Lost Data

May 22, 2024

This essay is the work of a dinobaby. Unlike some folks, no smart software improved my native ineptness.

This essay is the work of a dinobaby. Unlike some folks, no smart software improved my native ineptness.

A team in Egypt discovered something mysterious near the pyramids. I assume National Geographic will dispatch photographers. Archeologists will probe. Artifacts will be discovered. How much more is buried under the surface of Giza? People have been digging for centuries, and their efforts are rewarded. But what about the artifacts of the digital age?

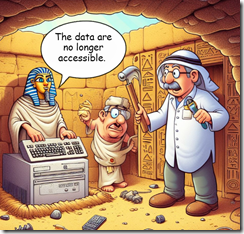

Upon opening the secret chamber, the digital construct explains to the archeologist from the future that there is a little problem getting the digital information. Thanks, MSFT Copilot.

My answer is, “Yeah, good luck.” The ephemeral quality of online information means that finding something buried near the pyramid of Djoser is going to be more rewarding than looking for the once findable information about MIC, RAC, and ZPIC on a US government Web site. The same void exists for quite a bit of human output captured in now-disappeared systems like The Point (Top 5% of the Internet) and millions of other digital constructs.

A survey report conducted by the Pew Research Center highlights link rot. The idea is simple. Click on a link and the indexed or pointed to content cannot be found. “When Online Content Disappears” has a snappy subtitle:

38 percent of Web pages that existed in 2013 are no longer accessible a decade later.

Wait, are national libraries like the Library of Congress supposed to keep “information.” What about the National Archives? What about the Internet Archive (an outfit busy in court)? What about the Google? (That’s the “all” the world’s information, right?) What about Bibliothèque nationale de France with its rich tradition of keeping French information?

News flash. Unlike the fungible objects unearthed in Egypt, data archeologists are going to have to buy old hard drives on eBay, dig through rubbish piles in “recycling” facilities, or scour yard sales for old machines. Then one has to figure out how to get the data. Presumably smart software can filter through the bits looking for useful data. My suggestion? Don’t count on this happening?

Here are several highlights from the Pew Report:

- Some 38% of webpages that existed in 2013 are not available today, compared with 8% of pages that existed in 2023.

- Nearly one-in-five tweets are no longer publicly visible on the site just months after being posted.

- 21% of all the government webpages we examined contained at least one broken link… Across every level of government we looked at, there were broken links on at least 14% of pages; city government pages had the highest rates of broken links.

The report presents a picture of lost data. Trying to locate these missing data will be less fruitful than digging in the sands of Egypt.

The word “rot” is associated with decay. The concept of “link rot” complements the business practices of government agencies and organizations once gathering, preserving, and organizing data. Are libraries at fault? Are regulators the problem? Are the content creators the culprits?

Sure, but the issue is that as the euphoria and reality of digital information slosh like water in a swimming pool during an earthquake, no one knows what to do. Therefore, nothing is done until knee jerk reflexes cause something to take place. In the end, no comprehensive collection plan is in place for the type of information examined by the Pew folks.

From my vantage point, online and digital information are significant features of life today. Like goldfish in a bowl, we are not able to capture the outputs of the digital age. We don’t understand the datasphere, my term for the environment in which much activity exists.

The report does not address the question, “So what?”

That’s part of the reason future data archeologists will struggle. The rush of zeros and ones has undermined information itself. If ignorance of these data create bliss, one might say, “Hello, Happy.”

Stephen E Arnold, May 22, 2023

Wanna Be Happy? Use the Internet

May 13, 2024

This essay is the work of a dinobaby. Unlike some folks, no smart software improved my native ineptness.

This essay is the work of a dinobaby. Unlike some folks, no smart software improved my native ineptness.

The glory days of the Internet have faded. Social media, AI-generated baloney, and brain numbing TikTok-esque short videos — Outstanding ways to be happy. What about endless online scams, phishing, and smishing, deep fake voices to grandma from grandchildren needing money — Yes, guaranteed uplifts to sagging spirits.

The idea of a payoff in a coffee shop is silly. Who would compromise academic standards for a latte and a pile of cash. Absolutely no one involved in academic pursuits. Good enough, MSFT Copilot. Good enough.

When I read two of the “real” news stories about how the Internet manufactures happiness, I asked myself, “Exactly what’s with this study?” The PR push to say happy things about online reminded me of the OII or Oxford Internet Institute and some of its other cheerleading. And what is the OII? It is an outfit which receives some university support, funds from private industry, and foundation cash; for example, the Shirley Institute.

In my opinion, it is often difficult to figure out if the “research” is wonky due to its methodology, the desire to keep some sources of funding writing checks, or a nifty way to influence policies in the UK and elsewhere. The magic of the “Oxford” brand gives the outfit some cachet for those who want to collect conference name tags to bedeck their office coat hangers.

The OII is back in the content marketing game. I read the BBC’s “Internet Access Linked to Higher Wellbeing, Study Finds” and the Guardian’s “Internet Use Is Associated with Greater Wellbeing, Global Study Finds.” Both articles are generated from the same PR-type verbiage. But the weirdness of the assertion is undermined by this statement from the BBC’s rewrite of the OII’s PR:

The study was not able to prove cause and effect, but the team found measures of life satisfaction were 8.5% higher for those who had internet access. Nor did the study look at the length of time people spent using the internet or what they used it for, while some factors that could explain associations may not have be considered.

The Oxford brand and the big numbers about a massive sample size cannot hide one awkward fact: There is little evidence that happiness drips from Internet use. Convenience? Yep. Entertainment? Yep. Crime? Yep. Self-harm, drug use or experimentation, meme amplification. Yep, yep, yep.

Several questions arise:

- Why is the message “online is good” suddenly big news? If anything, the idea runs counter to the significant efforts to contain access to potentially harmful online content in the UK and elsewhere. Gee, I wonder if the companies facing some type of sanctions are helping out the good old OII?

- What’s up with Oxford University itself? Doesn’t it have more substantive research to publicize? Perhaps Oxford should emulate the “Naked Scientist” podcast or lobby to get Melvin Bragg to report about more factual matters? Does Oxford have an identity crisis?

- And the BBC and the Guardian! Have the editors lost the plot? Don’t these professionals have first hand knowledge about the impact of online on children and young adults? Don’t they try to talk to their kids or grandkids at the dinner table when the youthful progeny of “real” news people are using their mobile phones?

I like facts which push back against received assumptions. But online is helping out those who use it needs a bit more precision, clearer thinking, and less tenuous cause-and-effect hoo-hah in my opinion.

Stephen E Arnold, May 13, 2024