Hewlett Packard and Autonomy: Search and $4 Billion

February 12, 2024

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

More than a decade ago, Hewlett Packard acquired Autonomy plc. Autonomy was one of the first companies to deploy what I call “smart software.” The system used Bayesian methods, still quite new to many in the information retrieval game in the 1990s. Autonomy kept its method in a black box assigned to a company from which Autonomy licensed the functions for information processing. Some experts in smart software overlook BAE Systems’ activity in the smart software game. That effort began in the late 1990s if my memory is working this morning. Few “experts” today care, but the dates are relevant.

Between the date Autonomy opened for business in 1996 and HP’s decision to purchase the company for about $8 billion in 2011, there was ample evidence that companies engaged in enterprise search and allied businesses like legal work processes or augmented magazine advertising were selling for much less. Most of the companies engaged in enterprise search simply went out of business after burning through their funds; for example, Delphes and Entopia. Others sold at what I thought we inflated or generous prices; for example, Vivisimo to IBM for about $28 million and Exalead to Dassault for 135 million euros.

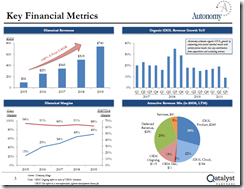

Then along comes HP and its announcement that it purchased Autonomy for a staggering $8 billion. I attended a search-related event when one of the presenters showed this PowerPoint slide:

The idea was that Autonomy’s systems generated multiple lines of revenue, including a cloud service. The key fact on the presentation was that the search-and-retrieval unit was not the revenue rocket ship. Autonomy has shored up its search revenue by acquisition; for example, Soundsoft, Virage, and Zantaz. The company also experimented with bundling software, services, and hardware. But the Qatalyst slide depicted a rosy future because of Autonomy management’s vision and business strategy.

Did I believe the analysis prepared by Frank Quatrone’s team? I accepted some of the comments about the future, and I was skeptical about others. In the period from 2006 to 2012, it was becoming increasingly difficult to overcome some notable failures in enterprise search. The poster child from the problems was Fast Search & Transfer. In a nutshell, Fast Search retreated from Web search, shutting down its Google competitor AllTheWeb.com. The company’s engaging founder John Lervik told me that the future was enterprise search. But some Fast Search customers were slow in paying their bills because of the complexity of tailoring the Fast Search system to a client’s particular requirements. I recall being asked to comment about how to get the Fast Search system to work because my team used it for the FirstGov.gov site (now USA.gov) when the Inktomi solution was no longer viable due to procurement rule changes. Fast Search worked, but it required the same type of manual effort that the Vivisimo system required. Search-and-retrieval for an organization is not a one size fits all thing, a fact Google learned with its spectacular failure with its truly misguided Google Search Appliance product. Fast Search ended with an investigation related to financial missteps, and Microsoft stepped in in 2008 and bought the company for about $1.2 billion. I thought that was a wild and crazy number, but I was one of the lucky people who managed to get Fast Search to work and knew that most licensees would not have the resources or talent I had at my disposal. Working for the White House has some benefits, particularly when Fast Search for the US government was part of its tie up with AT&T. Thank goodness for my counterpart Ms. Coker. But $1.2 billion for Fast Search? That in my opinion was absolutely bonkers from my point of view. There were better and cheaper options, but Microsoft did not ask my opinion until after the deal was closed.

Everyone in the HP Autonomy matter keeps saying the same thing like an old-fashioned 78 RPM record stuck in a groove. Thanks, MSFT Copilot. You produced the image really “fast.” Plus, it is good enough like most search systems.

What is the Reuters’ news story adding to this background? Nothing. The reason is that the news story focuses on one factoid: “HP Claims $4 Billion Losses in London Lawsuit over Autonomy Deal.” Keep in mind that HP paid $11 billion for Autonomy plc. Keep in mind that was 10 times what Microsoft paid for Fast Search. Now HP wants $4 billion. Stripping away everything but enterprise search, I could accept that HP could reasonably pay $1.2 billion for Autonomy. But $11 billion made Microsoft’s purchase of Fast Search less nutso. Because, despite technical differences, Autonomy and Fast Search were two peas in a pod. The similarities were significant. The differences were technical. Neither company was poised to grow as rapidly as their stakeholders envisioned.

When open source search options became available, these quickly became popular. Today if one wants serviceable search-and-retrieval for an enterprise application one can use a Lucene / Solr variant or pick one of a number of other viable open source systems.

But HP bought Autonomy and overpaid. Furthermore, Autonomy had potential, but the vision of Mike Lynch and the resources of HP were needed to convert the promise of Autonomy into a diversified information processing company. Autonomy could have provided high value solutions to the health and medical market; it could have become a key player in the policeware market; it could have leveraged its legal software into a knowledge pipeline for eDiscovery vendors to license and build upon; and it could have expanded its opportunities to license Autonomy stubs into broader OpenText enterprise integration solutions.

But what did HP do? It muffed the bunny. Mr. Lynch exited and set up a promising cyber security company and spent the rest of his time in courts. The Reuters’ article states:

Following one of the longest civil trials in English legal history, HP in 2022 substantially won its case, though a High Court judge said any damages would be significantly less than the $5 billion HP had claimed. HP’s lawyers argued on Monday that its losses resulting from the fraud entitle it to about $4 billion.

If I were younger and had not written three volumes of the Enterprise Search Report and a half dozen books about enterprise search, I would write about the wild and crazy years for enterprise search, its hits, its misses, and its spectacular failures (Yes, Google, I remember the Google Search Appliance quite well.) But I am a dinobaby.

The net net is HP made a poor decision and now years later it wants Mike Lynch to pay for HP’s lousy analysis of the company, its management missteps within its own Board of Directors, and its decision to pay $11 billion for a company in a sector in which at the time simply being profitable was a Herculean achievement. So this dinobaby says, “Caveat emptor.”

Stephen E Arnold, February 12, 2024

The Next Big Thing in Search: A Directory of Web Sites

February 12, 2024

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

In the early 1990s, an entrepreneur with whom I had worked in the 1980s convinced me to work on a directory of Web sites. Yahoo was popular at the time, but my colleague had a better idea. The good news is that our idea worked and the online service we built became part of the CMGI empire. Our service was absorbed by one of the leading finding services at the time. Remember Lycos? My partner and I do. Now the Web directory is back decades after those original Yahooligans and our team provided a useful way to locate a Web site.

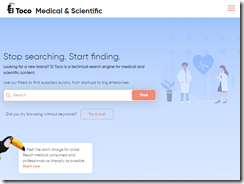

“Search Chatbots? Pah, This Startup’s Trying on Yahoo’s Old Outfit of Web Directories” presents information about the utility of a directory of Web sites and captures some interesting observations about the findability service El Toco.

The innovator driving the directory concept is Thomas Chopping, a “UK based economist.” He made several observations in a recent article published by the British outfit The Register; for example:

“During the decades since it launched, we’ve been watching Google steadily trying to make search more predictive, by adding things like autocomplete and eventually instant answers,” Chopping told The Register. “This has the byproduct of increasing the amount of time users spend on their site, at the expense of visiting the underlying sources of the data.”

The founder of El Toco also notes:

It’s impossible to browse with conversational-style search tools, which are entirely focused on answering questions. “Right now, this is playing into the hands of Meta and TikTok, because it takes so much effort to find good quality websites via search engines that people stopped bothering.

El Taco wants to facilitate browsing, and the model is a directory listing. The user can browse and click. The system displays a Web site for the user to scan, read, or bookmark.

Another El Taco principle is:

“We don’t need the user’s personal data to work out which results to show, because the user can express this on their own. We don’t need AI to turn the search into a conversation, because this can be done with a few clicks of the user interface

The economist-turned-entrepreneur points out:

“Charging users for Web search is a model which clearly doesn’t work, thanks to Neeva for demonstrating that, so we allow adverts but if the users care they can go into a menu and simply switch them off.”

Will El Taco gain traction? My team and I have been involved in information retrieval for decades. From indexing information about nuclear facilities to providing some advice to an AI search start up a few months ago. I have learned that predicting what will become the next big thing in findability is quite difficult.

A number of interesting Web search solutions are available. Some are niche-focused like Biznar. Others are next-generation “phinding” services like Phind.com. Others are metasearch solutions like iSeek. Some are less crazy Google-style systems like Swisscows. And there are more coming every day.

Why? Let me share several observations or “learnings” from a half century of working in the information retrieval sector:

- People have different information needs and a one-size-fits-all search system is fraught with problems. One person wants to search for “pizza near me”. Another wants information about Dark Web secure chat services.

- Almost everyone considers themselves a good or great online searcher. Nothing could be further from the truth. Just ask the OSINT professionals at any intelligence conference.

- Search companies with some success often give in to budgeting for a minimally viable system, selling traffic or user data, and to dark patterns in pursuit of greater revenue.

- Finding information requires effort. Convenience, however, is the key feature of most finding systems. Microfilm is not convenient; therefore, it sucks. Looking at research data takes time and expertise; therefore, old-fashioned work sucks. Library work involving books is not for everyone; therefore, library research sucks. Only a tiny percentage of online users want to exert significant effort finding, validating, and making sense of information. Most people prefer to doom scroll or watch dance videos on a mobile device.

Net net: El Taco is worth a close look. I hope that editorial policies, human curation, and frequent updating become the new normal. I am just going to remain open minded. Information is an extremely potent tool. If I tell you human teeth can explode, do you ask for a citation? Do you dismiss the idea because of your lack of knowledge? Do you begin to investigate of high voltage on the body of a person who works around a 133 kV transmission line? Do you dismiss my statement because I am obviously making up a fact because everyone knows that electricity is 115 to 125 volts?

Unfortunately only subject matter experts operating within an editorial policy and given adequate time can figure out if a scientific paper contains valid data or made-up stuff like that allegedly crafted by the former presidents of Harvard and Stanford University and probably faculty at the university closest to your home.

Our 1992 service had a simple premise. We selected Web sites which contained valid and useful information. We did not list porn sites, stolen software repositories, and similar potentially illegally or harmful purveyors of information. We provided the sites our editors selected with an image file that was our version of the old Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval.

The idea was that in the early days of the Internet and Web sites, a parent or teacher could use our service without too much worry about setting off a porn storm or a parent storm. It worked, we sold, and we made some money.

Will the formula work today? Sure, but excellence and selectivity have been key attributes for decades. Give El Taco a look.

Stephen E Arnold, February 12, 2024

Scattering Clouds: Price Surprises and Technical Labyrinths Have an Impact

February 12, 2024

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

Yep, the cloud. A third-party time sharing services with some 21st-century add ons. I am not too keen on the cloud even though I am forced to use it for certain specific tasks. Others, however, think nothing of using the cloud like an invisible and infinite USB stick. “2023 Could Be the Year of Public Cloud Repatriation” strikes me as a “real” news story reporting that others are taking a look at the sky, spotting threatening clouds, and heading to a long-abandoned computer room to rethink their expenditures.

The write up reports:

Many regard repatriating data and applications back to enterprise data centers from a public cloud provider as an admission that someone made a big mistake moving the workloads to the cloud in the first place. I don’t automatically consider this a failure as much as an adjustment of hosting platforms based on current economic realities. Many cite the high cost of cloud computing as the reason for moving back to more traditional platforms.

I agree. However, there are several other factors which may reflect more managerial analysis than technical acumen; specifically:

- The cloud computing solution was better, faster, and cheaper. Better than an in house staff? Well, not for everyone because cloud companies are not working overtime to address user / customer problems. The technical personnel have other fires, floods, and earthquakes. Users / customers have to wait unless the user / customer “buys” dedicated support staff.

- So the “cheaper” argument becomes an issue. In addition to paying for escalated support, one has to deal with Byzantine pricing mechanisms. If one considers any of the major cloud providers, one can spend hours reading how to manage certain costs. Data transfer is a popular subject. Activated but unused services are another. Why is pricing so intricate and complex? Answer: Revenue for the cloud providers. Many customers are confident the big clouds are their friend and have their best financial interests at heart. That’s true. It is just that the heart is in the cloud computer books, not the user / customer balance sheets.

- And better? For certain operations, a user / customer has limited options. The current AI craze means the cloud is the principal game in town. Payroll, sales management, and Webby stuff are also popular functions to move to the cloud.

The rationale for shifting to the cloud varies, but there are some themes which my team and I have noted in our work over the years:

First, the cloud allowed “experts” who cost a lot of money to be hired by the cloud vendor. Users / customers did not have to have these expensive people on their staff. Plus, there are not that many experts who are really expert. The cloud vendor has the smarts to hire the best and the resources to pay these people accordingly… in theory. But bean counters love to cut costs so IT professionals were downsized in many organizations. The mythical “power user” could do more and gig workers could pick up any slack. But the costs of cloud computing held a little box with some Tannerite inside. Costs for information technology were going up. Wouldn’t it be cheaper to do computing in house? For some, the answer is, “Yes.”

An ostrich company with its head in the clouds, not in the sand. Thanks, MidJourney, what a not-even-good-enough illustration.

Second, most organizations lacked the expertise to manage a multi-cloud set up. When an organization has two or more clouds, one cannot allow a cloud company to manage itself and one or more competitors. Therefore, organizations had to add to their headcount a new and expensive position: A cloud manager.

Third, the cloud solutions are not homogeneous. Different rules of the road, different technical set up, and different pricing schemes. The solution? Add another position: A technical manager to manage the cloud technologies.

I will stop with these three points. One can rationalize using the cloud easily; for example a government agency can push tasks to the cloud. Some work in government agencies consists entirely of attending meetings at which third-party contractors explain what they are doing and why an engineering change order is priority number one. Who wants to do this work as part of a nine to five job?

But now there is a threat to the clouds themselves. That is security. What’s more secure? Data in a user / customer server facility down the hall or in a disused building in Piscataway, New Jersey, or sitting in a cloud service scattered wherever? Security? Cloud vendors are great at security. Yeah, how about those AWS S3 buckets or the Microsoft email “issue”?

My view is that a “where should our computing be done and where should our data reside” audit be considered by many organizations. People have had their heads in the clouds for a number of years. It is time to hold a meeting in that little-used computer room and do some thinking.

Stephen E Arnold, February 12, 2024

What Does Eroding Intelligence Create? Take-a-Chance Apps in Curated App Stores

February 9, 2024

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

I am a real and still-alive dinobaby. I read “Undergraduates’ Average IQ Has Fallen 17 Points Since 1939. Here’s Why.” The headline tells the story. At least, Dartmouth is planning to use testing to make sure its admitted students can read and write. But it appears that interesting people are empowering certain business tactics whether they have great test scores or not.

“Warning: Fraudulent App Impersonating LastPass Currently Available in Apple App Store” strikes me as a good example of how tactics take advantage of what one might call somewhat slow or unaware people. The write up states:

The app attempts to copy our branding and user interface, though close examination of the posted screenshots reveal misspellings and other indicators the app is fraudulent.

Are there similarly structured apps in the Goggle Play store? You bet. A couple of days ago, I downloaded and paid a $1.95 for an app that allegedly would display the old-school per-core graphic load which Microsoft removed from Task Manager. Guess what? It did not load.

Several observations:

- The “stores” are not preventing problematic apps from being made available to users

- The people running the store are either unable to screen apps or just don’t care

- The baloney about curation is exactly that.

I wonder if the people running these curated app stores are unaware of what these misfires do to a customer. On the other hand, perhaps the customers neither know nor care that curated apps are creeping into fraud territory.

Stephen E Arnold, February 8, 2024

School Technology: Making Up Performance Data for Years

February 9, 2024

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

What is the “make up data” trend? Why is it plaguing educational institutions. From Harvard to Stanford, those who are entrusted with shaping young-in-spirit minds are putting ethical behavior in the trash can. I think I know, but let’s look at allegations of another “synthetic” information event. For context in the UK there is a government agency called the Office for Standards in Education, Children’s Services and Skills.” The agency is called OFSTED. Now let’s go to the “real” news story.“

A possible scene outside of a prestigious academic institution when regulations about data become enforceable… give it a decade or two. Thanks, MidJourney. Two tries and a good enough illustration.

“Ofsted Inspectors Make Up Evidence about a School’s Performance When IT Fails” reports:

Ofsted inspectors have been forced to “make up” evidence because the computer system they use to record inspections sometimes crashes, wiping all the data…

Quite a combo: Information technology and inventing data.

The article adds:

…inspectors have to replace those notes from memory without telling the school.

Will the method work for postal investigations? Sure. Can it be extended to other activities? What about data pertinent to the UK government initiates for smart software?

Stephen E Arnold, February 9, 2024

Old News Flash: Old-Fashioned Learning Methods Work. Amazing!

February 9, 2024

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

Humans are tactile, visual learners with varying attention span lengths. Unfortunately attention spans are getting shorter due to kids’ addiction to small screens. Their small screen addiction is affecting how they learn and retain information. The Guardian shares news about an educational study that didn’t need to be researched because anecdotal evidence is enough: “A Groundbreaking Study Shows Kids Learn Better On Paper, Not Screens.” American student reading scores are at an all time low. Educators, parents, bureaucrats, and everyone are concerned and running around like decapitated chickens.

Thirteen-year-olds’ text comprehension skills have lowered by four points since the 2019-2020 pandemic school year and the average rate has fallen seven points compared to 2012. These are the worst results since reading levels were first recorded in 1971.

Biden’s administration is blaming remote learning and the pandemic. Conservative politicians are blaming teacher unions because they encouraged remote learning. Remote learning is the common denominator. Remote learning is the scapegoat but the claim is true. Kids will avoid school at all costs and the pandemic was the ultimate extended vacation.

There’s an even bigger culprit because COVID can’t be blamed in the coming years. The villains are computers and mobile devices. Unfortunately anecdotal evidence isn’t enough to satisfy bigwigs (which is good in most cases) so Columbia University’s Teachers College tested paper vs. screens for “deeper reading” and “shallow reading.” Here’s what they found:

“Using a sample of 59 children aged 10 to 12, a team led by Dr Karen Froud asked its subjects to read original texts in both formats while wearing hair nets filled with electrodes that permitted the researchers to analyze variations in the children’s brain responses. Performed in a laboratory at Teachers College with strict controls, the study – which has not yet been peer reviewed – used an entirely new method of word association in which the children “performed single-word semantic judgment tasks” after reading the passages. Vital to the usefulness of the study was the age of the participants – a three-year period that is “critical in reading development” – since fourth grade is when a crucial shift occurs from what another researcher describes as “learning to read” to “reading to learn”.”

Don’t chuck printed books in the recycling bin yet! Printed tools are still the best way to learn and retain information. Technology is being thrust into classrooms from the most remote to inner cities. Technology is wonderful in spreading access to education but it’s not increasing literacy and other test scores. Technology is being promoted instead of actually teaching kids to learn.

As a trained librarian, the utility of reading books, taking notes in a notebook, and chasing information in reference materials seems obvious. But obvious to me is not obvious to others.

Whitney Grace, February 9, 2024

A Reminder: AI Winning Is Skewed to the Big Outfits

February 8, 2024

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

I have been commenting about the perception some companies have that AI start ups focusing on search will eventually reduce Google’s dominance. I understand the desire to see an underdog or a coalition of underdogs overcome a formidable opponent. Hollywood loves the unknown team which wins the championship. Movie goers root for an unlikely boxing unknown to win the famous champion’s belt. These wins do occur in real life. Some Googlers favorite sporting event is the NCAA tournament. That made-for-TV series features what are called Cinderella teams. (Will Walt Disney Co. sue if the subtitles for a game employees the the word “Cinderella”? Sure, why not?)

I believe that for the next 24 to 36 months, Google will not lose its grip on search, its services, or online advertising. I admit that once one noses into 2028, more disruption will further destabilize Google. But for now, the Google is not going to be derailed unless an exogenous event ruins Googzilla’s habitat.

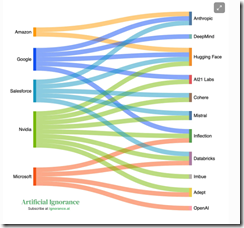

I want to direct attention to the essay “AI’s Massive Cash Needs Are Big Tech’s Chance to Own the Future.” The write up contains useful information about selected players in the artificial intelligence Monopoly game. I want to focus on one “worm” chart included in the essay:

Several things struck me:

- The major players are familiar; that is, Amazon, Google, Microsoft, Nvidia, and Salesforce. Notably absent are IBM, Meta, Chinese firms, Western European companies other than Mistral, and smaller outfits funded by venture capitalists relying on “open source AI solutions.”

- The five major companies in the chart are betting money on different roulette wheel numbers. VCs use the same logic by investing in a portfolio of opportunities and then pray to the MBA gods that one of these puppies pays off.

- The cross investments ensure that information leaks from the different color “worms” into the hills controlled by the big outfits. I am not using the collusion word or the intelligence word. I am just mentioned that information has a tendency to leak.

- Plumbing and associated infrastructure costs suggest that start ups may buy cloud services from the big outfits. Log files can be fascinating sources of information to the service providers engineers too.

My point is that smaller outfits are unlikely to be able to dislodge the big firms on the right side of the “worm” graph. The big outfits can, however, easily invest in, acquire, or learn from the smaller outfits listed on the left side of the graph.

Does a clever AI-infused search start up have a chance to become a big time player. Sure, but I think it is more likely that once a smaller firm demonstrates some progress in a niche like Web search, a big outfit with cash will invest, duplicate, or acquire the feisty newcomer.

That’s why I am not counting out the Google to fall over dead in the next three years. I know my viewpoint is not one shared by some Web search outfits. That’s okay. Dinobabies often have different points of view.

Stephen E Arnold, February 8, 2024

Does Cheap and Sneaky Work Better than Expensive and Hyperbole?

February 8, 2024

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

My father was a member of the Sons of the American Revolution (SAR). He loved reading about that historical “special operation.” I think he imagine himself in a make-shift uniform, hiding behind some bushes, and then greeting the friend of George III with some old-fashioned malice. My hunch is that John Arnold’s descendants wrote anti-British editorials and gave speeches. But what do I know? Not much that’s for sure.

The David and Goliath trope may be applicable to the cheap drone tactic. Thanks, MSFT Copilot Bing thing. Good enough.

I thought about how a rag-tag, under-supplied collection of colonials could bedevil the British when I read The Guardian’s essay “Deadly, Cheap and Widespread: How Iran-Supplied Drones Are Changing the Nature of Warfare.” The write up opines that the drone which killed several Americans in Iraq:

is most likely to the smaller Shahed 101 or delta winged Shahed 131, both believed to be in Kataib Hezbollah’s arsenal …with estimated ranges of at least 700km (434 miles) and a cost of $20,000 (£15,700) or more. (Source Fabian Hinz, a weapons expert)

The point strikes me as a variant of David versus Goliath. The giant gets hurt by a lesser opponent with a cheap weapon. Iran is using drones, not exotic hardware like the F-16s Türkiye craves. A flimsy drone does not require the obvious paraphernalia of power the advanced jet does. Tin snips, some parts from Shenzhen retail outlets, and model airplane controls. No hangers, mechanics, engineers, and specially trained pilots.

Shades of the Colonials I think. The article continues:

The drones …are best considered cheap substitutes for guided cruise missiles, most effective against soft or “static structures” which force those under threat to “either invest money in defenses or disperse and relocate which renders things like aircraft on bases more inefficient”

Is there a factoid in this presumably accurate story from a British newspaper? Yes. My take-away is that simple and basic can do considerable harm. Oh, let me add “economical”, but that is rarely a popular concept among some government entities and approved contractors.

Net net: How about thinking like some of those old-time Revolutionaries in what has become the US?

Stephen E Arnold, February 8, 2024

AI, AI, Ai-Yi-Ai: Too Much Already

February 8, 2024

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

I want to say that smart software and systems are annoying me, not a lot, just a little.

Al algorithms are advancing society from science fiction into everyday life. AI algorithms are indexes and math. But the algorithms are still processes simulating reason mental functions. We’ve come to think, unfortunately, that AI like ChatGPT are sentient and capable of rational thought.

Mita Williams wrote a the post “I Will Dropkick You If You Refer To An LLM As A Librarian” on her blog Librarian of Things. In her post, she explains that AI is being given more credit than it deserves and large language models (LLMs) are being compared to libraries. While Williams responds to these assertions as a true academic with citations and explanations, her train of thought is more in line with Mark Twain and Jonathan Swift.

Twain and Swift are two great English-speaking authors and satirists. They made outrageous claims and their essays will make many people giggle or laugh. Williams should rewrite her post like them. Her humor would probably be lost on the majority of readers, though. Here’s the just of her post: A lot of people are saying AI and their LLM learning tools are like giant repositories of knowledge capable of human emotion, reasoning, and intelligence. Williams argues they’re not and that assumption should be reevaluated.

Furthermore, smart software can be configured to do some things more quickly and accurately rate than some human. Williams is right:

“This is why I will not describe products like ChatGPT as Artificial General Intelligence. This is why I will avoid using the word learned when describing the behavior of software, and will substitute that word with associated instead. Your LLM is more like a library catalogue than a library but if you call it a library, I won’t be upset. I recognize that we are experiencing the development of new form of cultural artifact of massive import and influence. But an LLM is not a librarian and I won’t let you call it that.”

I am a somewhat critical librarian. I like books. Smart software … not so much at this time.

Whitney Grace, February 8, 2024

Universities and Innovation: Clever Financial Plays May Help Big Companies, Not Students

February 7, 2024

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

This essay is the work of a dumb dinobaby. No smart software required.

I read an interesting essay in The Economist (a newspaper to boot) titled “Universities Are Failing to Boost Economic Growth.” The write up contained some facts anchored in dinobaby time; for example, “In the 1960s the research and development (R&D) unit of DuPont, a chemicals company, published more articles in the Journal of the American Chemical Society than the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Caltech combined.”

A successful academic who exists in a revolving door between successful corporate employment and prestigious academic positions innovate with [a] a YouTube program, [b] sponsors who manufacture interesting products, and [c] taking liberties with the idea of reproducible results from his or her research. Thanks, MSFT Copilot Bing thing. Getting more invasive today, right?

I did not know that. I recall, however, that my former boss at Booz, Allen & Hamilton in the mid-1970s had me and couple of other compliant worker bees work on a project to update a big-time report about innovation. My recollection is that our interviews with universities were less productive than conversations held at a number of leading companies around the world. The gulf between university research departments had yet to morph into what were later called “technology transfer departments.” Over the years, as the Economist newspaper points out:

The golden age of the corporate lab then came to an end when competition policy loosened in the 1970s and 1980s. At the same time, growth in university research convinced many bosses that they no longer needed to spend money on their own. Today only a few firms, in big tech and pharma, offer anything comparable to the DuPonts of the past.

The shift, from my point of view, was that big companies could shift costs, outsource research, and cut themselves free from the wonky wizards that one could find wandering around the Cherry Hill Mall near the now-gone Bell Laboratories.

Thus, the schools became producers of innovation.

The Economist newspaper considers the question, “Why can’t big outfits surf on these university insights?” My question is, “Is the Economist newspaper overlooking the academic linkages that exist between the big companies producing lots of cash and a number of select universities. IBM is proud to be camped out at MIT. Google operates two research annexes at Stanford University and the University of Washington. Even smaller companies have ties; for example, Megatrends is close to Indiana University by proximity and spiritually linked to a university in a country far away. Accidents? Nope.

The Economist newspaper is doing the Oxford debate thing: From a superior position, the observations are stentorious. The knife like insights are crafted to cut those of lesser intellect down to size. Chop slice dice like a smart kitchen appliance.

I noted this passage:

Perhaps, with time, universities and the corporate sector will work together more profitably. Tighter competition policy could force businesses to behave a little more like they did in the post-war period, and beef up their internal research.

Is the Economist newspaper on the right track with this university R&D and corporate innovation arguments?

In a word, “Yep.”

Here’s my view:

- Universities teamed up with companies to get money in exchange for cheaper knowledge work subsidized by eager graduate students and PR savvy departments

- Companies used the tie ups to identify ideas with the potential for commercial application and the young at heart and generally naive students, faculty, and researchers as a recruiting short cut. (It is amazing what some PhDs would do for a mouse pad with a prized logo on it.)

- Researchers, graduate students, esteemed faculty, and probably motivated adjunct professors with some steady income after being terminated in a “real” job started making up data. (Yep, think about the bubbling scandals at Harvard University, for instance.)

- Universities embraced the idea that education is a business. Ah, those student loan plays were useful. Other outfits used the reputation to recruit students who would pay for the cost of a degree in cash. From what countries were these folks? That’s a bit of a demographic secret, isn’t it?

Where are we now? Spend some time with recent college graduates. That will answer the question, I believe. Innovation today is defined narrowly. A recent report from Google identified companies engaged in the development of mobile phone spyware. How many universities in Eastern Europe were on the Google list? Answer: Zero. How many companies and state-sponsored universities were on the list? Answer: Zero. How comprehensive was the listing of companies in Madrid, Spain? Answer: Incomplete.

I want to point out that educational institutions have quite distinct innovation fingerprints. The Economist newspaper does not recognize these differences. A small number of companies are engaged in big-time innovation while most are in the business of being cute or clever. The Economist does not pay much attention to this. The individuals, whether in an academic setting or in a corporate environment, are more than willing to make up data, surf on the work of other unacknowledged individuals, or suck of good ideas and information and then head back to a home country to enjoy a life better than some of their peers experience.

If we narrow the focus to the US, we have an unrecognized challenge — Dealing with shaped or synthetic information. In a broader context, the best instruction in certain disciplines is not in the US. One must look to other countries. In terms of successful companies, the financial rewards are shifting from innovation to me-too plays and old-fashioned monopolistic methods.

How do I know? Just ask a cashier (human, not robot) to make change without letting the cash register calculate what you will receive. Is there a fix? Sure, go for the next silver bullet solution. The method is working quite well for some. And what does “economic growth” mean? Defining terms can be helpful even to an Oxford Union influencer.

Stephen E Arnold, February 7, 2024